Korea

Korea 한국 (South Korean) 조선 (North Korean) | |

|---|---|

Anthem:

| |

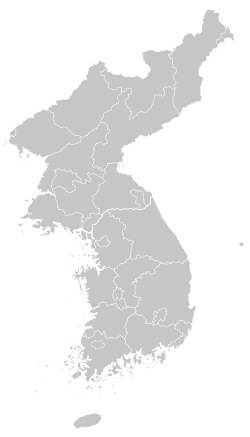

Korea shown in dark green | |

| Capital | |

| Largest city | Seoul |

| Official languages | Korean |

| Official script |

|

| Demonym(s) | Korean |

| Government | In dispute between South Korea and North Korea |

| Yoon Suk Yeol | |

| Kim Jong Un[a] | |

| Han Duck-soo | |

| Kim Tok Hun | |

| Legislature | |

| Establishment | |

• Gojoseon | 2333 BCE (mythological) |

| 194 BCE | |

| 57 BCE | |

| 668 | |

| 918 | |

| 17 July 1392 | |

| 12 October 1897 | |

| 29 August 1910 | |

| 1 March 1919 | |

• Establishment of the Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea | 11 April 1919 |

| 2 September 1945 | |

• Establishment of the Republic of Korea | 15 August 1948 |

• Establishment of the Democratic People's Republic of Korea | 9 September 1948 |

| 25 June 1950 – 27 July 1953 | |

• Both Koreas admitted to the UN | 17 September 1991 |

| Area | |

• Total | 223,172 km2 (86,167 sq mi)[1][2] |

| Population | |

• 2017 estimate | 77,000,000 |

• Density | 349.06/km2 (904.1/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+09 (Korea Standard Time and Pyongyang Time) |

| Drives on | right |

| Calling code |

|

| Internet TLD | |

Korea (Korean: 한국, romanized: Hanguk in South Korea, or 조선, Chosŏn in North Korea) is a peninsular region in East Asia consisting of the Korean Peninsula (한반도, Hanbando in South Korea, or 조선반도, Chosŏnbando in North Korea), Jeju Island, and smaller islands. Since the end of World War II in 1945, it has been politically divided at or near the 38th parallel; in 1948, two states declared independence, both claiming sovereignty over the entire region: North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea; DPRK) in its northern half and South Korea (Republic of Korea; ROK) in the south, which fought the Korean War from 1950 to 1953. The region is bordered by China to the north and Russia to the northeast, across the Amnok (Yalu) and Duman (Tumen) rivers, and is separated from Japan to the southeast by the Korea Strait.

Known human habitation of the Korean peninsula dates to 40,000 BC.[3] The kingdom of Gojoseon, which according to tradition was founded in 2333 BC, fell to the Han dynasty in 108 BC. It was followed by the Three Kingdoms period, in which Korea was divided into Goguryeo, Baekje, and Silla. In 668 AD, Silla conquered Baekje and Goguryeo with the aid of the Tang dynasty, forming Unified Silla; Balhae succeeded Goguryeo in the north. In the late 9th century, Unified Silla collapsed into three states, beginning the Later Three Kingdoms period. In 918, Goguryeo was resurrected as Goryeo, which achieved what has been called a "true national unification" by Korean historians, as it unified both the Later Three Kingdoms and the ruling class of Balhae after its fall.[4] Goryeo, whose name developed into the modern exonym "Korea", was highly cultured and saw the invention of the first metal movable type. During the 13th century, Goryeo became a vassal state of the Mongol Empire. Goryeo overthrew Mongol rule before falling to a coup led by General Yi Seong-gye, who established the Joseon dynasty in 1392. The first 200 years of Joseon were marked by peace; the Korean alphabet was created and Confucianism became influential. This ended with Japanese and Qing invasions, which brought devastation to Joseon and led to Korean isolationism. After the invasions, an isolated Joseon experienced another nearly 200-year period of peace and prosperity, along with cultural and technological development. In the final years of the 19th century, Japan forced Joseon to open up and Joseon experienced turmoil such as the Gapsin Coup, Donghak Peasant Revolution, and the assassination of Empress Myeongseong. In 1895, Japan defeated China in the First Sino-Japanese War and China lost suzerainty over Korea and Korea was placed under further Japanese influence. In 1897, the centuries old Joseon was replaced by the Korean Empire with the Joseon's last king, Gojong, becoming the Emperor of the Korean Empire. Japan's further victory in the 1904–1905 Russo-Japanese War, expelled Russian influence in Korea and Manchuria. In 1905, the Korean Empire became a protectorate of the Empire of Japan. In 1910, the Empire of Japan officially annexed the Korean peninsula.

Korea under Japanese rule was marked by industrialization and modernization, economic exploitation, and brutal suppression of the Korean independence movement, as reflected in the 1919 March First Movement. The Japanese suppressed Korean culture, and during World War II forcefully mobilized millions of Koreans to support its war effort. In 1945, Japan surrendered to the Allies, and the Soviet Union and United States agreed to divide Korea into two military occupation zones divided by the 38th parallel, with the Soviet zone in the north and American zone in the south. The division was meant to be temporary, with plans for Korea to be reunited under a single government. In 1948, the DPRK and ROK were established with the backing of each power, and ongoing tensions led to the outbreak of the Korean War in 1950, which came to involve U.S.-led United Nations and communist Chinese forces. The war ended in stalemate in 1953, but without a peace treaty. A demilitarized zone was created between the countries, approximating the original partition.

This status contributes to the high tensions that divide the peninsula, and both states claim to be the sole legitimate government of Korea. South Korea is a regional power and a developed country, with its economy ranked as the world's fourteenth-largest by GDP (PPP). Its armed forces are one of the world's strongest militaries, with the world's second-largest standing army by military and paramilitary personnel. South Korea has been renowned for its globally influential pop culture, particularly in music (K-pop) and cinema, a phenomenon referred to as the Korean Wave. North Korea follows Songun, a "military first" policy which prioritizes the Korean People's Army in state affairs and resources. It possesses nuclear weapons, and is the country with the highest number of military personnel, with a total of 7.8 million active, reserve, and paramilitary personnel, or approximately 30% of its population. Its active duty army of 1.3 million soldiers is the fourth-largest in the world, consisting of 4.9% of its population. North Korea is widely considered to have the worst human rights record in the world.

Etymology

| Korea | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North Korean name | |||||||

| Chosŏn'gŭl | 조선 | ||||||

| Hancha | 朝鮮 | ||||||

| |||||||

| South Korean name | |||||||

| Hangul | 한국 | ||||||

| Hanja | 韓國 | ||||||

| |||||||

"Korea" is the modern spelling of "Corea", a name attested in English as early as 1614.[5][6] "Corea" is derived from the name of the ancient kingdom of Goryeo.[7] Korea was transliterated as Cauli in The Travels of Marco Polo,[8] of the Chinese 高麗 (MC: Kawlej,[9] mod. Gāolì). This was the Hanja for the Korean kingdom of Goryeo (Korean: 고려; MR: Koryŏ), which ruled most of the Korean peninsula during the 12th century. Korea's introduction to the West resulted from trade and contact with merchants from Arabic lands,[10] with some records dating back as far as the 9th century.[11] Goryeo's name was a continuation of Goguryeo (Koguryŏ) the northernmost of the Three Kingdoms of Korea, which was officially known as Goryeo beginning in the 5th century.[12] The original name was a combination of the adjectives ("high, lofty") with the name of a local Yemaek tribe, whose original name is thought to have been either "Guru" (溝樓, 'Walled City', inferred from some toponyms in Chinese historical documents) or "Gauri" (가우리, 'Center'). With expanding British and American trade following the opening of Korea in the late 19th century, the spelling "Korea" appeared and gradually grew in popularity.[5] The name Korea is now commonly used in English contexts by both North and South Korea.

In South Korea, Korea as a whole is referred to as Hanguk (한국; lit. country of the Han, [haːnɡuk]). The name references Samhan, referring to the Three Kingdoms of Korea, not the ancient confederacies in the southern Korean Peninsula.[13][14] Although written in Hanja as 韓, 幹, or 刊, this Han has no relation to the Chinese place names or peoples who used those characters but was a phonetic transcription (OC: *Gar, MC: Han[9] or Gan) of a native Korean word that seems to have had the meaning "big" or "great", particularly in reference to leaders. It has been tentatively linked with the title khan used by the nomads of Manchuria and Central Asia.

In North Korea, Korea as a whole is referred to as Joseon (조선; lit. [land of the] Morning Calm, [tɕosʰʌn]). Joseon is the modern Korean pronunciation of the Hanja 朝鮮, which is also the basis of the word for Korea as a whole in Japan (朝鮮, Chōsen), China (朝鮮; Cháoxiǎn), and Vietnam (Triều Tiên). "Great Joseon" was the name of the kingdom ruled by the Joseon dynasty from 1392 until their declaration of the short-lived Great Korean Empire in 1897. King Taejo had named them for the earlier Gojoseon (고조선), who ruled northern Korea from its legendary prehistory until their conquest in 108 BCE by China's Han Empire. The Go- in Gojoseon is the Hanja word 古 and simply means "ancient" or "old"; it is a modern usage to distinguish the ancient Joseon from the later dynasty. It is unclear whether Joseon was a transcription of a native Korean name (OC *T[r]awser, MC Trjewsjen)[9] or a partial translation into Chinese of the Korean capital Asadal (아사달),[15] whose meaning has been reconstructed as "Morning Land" or "Mountain".

History

| History of Korea |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

|

|

Prehistory

The Korean Academy claimed ancient hominid fossils originating from about 100,000 BCE in the lava at a stone city site in Korea. Fluorescent and high-magnetic analyses indicate the volcanic fossils may be from as early as 300,000 BCE.[16] The best preserved Korean pottery goes back to the paleolithic times around 10,000 BCE and the Neolithic period begins around 6000 BCE.

Beginning around 300 BC, the Japonic-speaking Yayoi people from the Korean Peninsula entered the Japanese islands and displaced or intermingled with the original Jōmon inhabitants.[17] The linguistic homeland of Proto-Koreans is located somewhere in Southern Siberia / Manchuria, such as the Liao river area or the Amur region. Proto-Koreans arrived in the southern part of the Korean Peninsula at around 300 BC, replacing and assimilating Japonic-speakers and likely causing the Yayoi migration.[18]

Gojoseon

According to Korean legend, Dangun, a descendant of Heaven, established Gojoseon in 2333 BCE. In 108 BCE, the Han dynasty defeated Gojoseon and installed four commanderies in the northern Korean peninsula. Three of the commanderies fell or retreated westward within a few decades, but the Lelang Commandery remained as a center of cultural and economic exchange with successive Chinese dynasties for four centuries. By 313, Goguryeo annexed all of the Chinese commanderies.

Proto–Three Kingdoms

The Proto–Three Kingdoms period, sometimes called the Multiple States Period, is the earlier part of what is commonly called the Three Kingdoms Period, following the fall of Gojoseon but before Goguryeo, Baekje, and Silla fully developed into kingdoms.

This time period saw numerous states spring up from the former territories of Gojoseon, which encompassed northern Korea and southern Manchuria. With the fall of Gojoseon, southern Korea entered the Samhan period.

Located in the southern part of Korea, Samhan referred to the three confederacies of Mahan, Jinhan, and Byeonhan. Mahan was the largest and consisted of 54 states. Byeonhan and Jinhan both consisted of twelve states, bringing a total of 78 states within the Samhan. These three confederacies eventually developed into Baekje, Silla, and Gaya.

Three Kingdoms

This section may contain excessive or inappropriate references to self-published sources. (November 2022) |

The Three Kingdoms of Korea consisted of Goguryeo, Silla, and Baekje. Silla and Baekje controlled the southern half of the Korean Peninsula, maintaining the former Samhan territories, while Goguryeo controlled the northern half of the Korean Peninsula, Manchuria and the Liaodong Peninsula, uniting Buyeo, Okjeo, Dongye, and other states in the former Gojoseon territories.[19]

Goguryeo was a highly militaristic state,[20][21] and a large empire in East Asia,[22][23][24][25] reaching its zenith in the 5th century when its territories expanded to encompass most of Manchuria to the north, parts of Inner Mongolia to the west,[26] parts of Russia to the east,[27] and the Seoul region to the south.[28] Goguryeo experienced a golden age under Gwanggaeto the Great and his son Jangsu,[29][30][31][32] who both subdued Baekje and Silla during their times, achieving a brief unification of the Three Kingdoms of Korea and becoming the most dominant power on the Korean Peninsula.[33][34] In addition to contesting for control of the Korean Peninsula, Goguryeo had many military conflicts with various Chinese dynasties,[35][self-published source?] most notably the Goguryeo–Sui War, in which Goguryeo defeated a huge force said to number over a million men.[36][37][38][39][40] In 642, the powerful general Yeon Gaesomun led a coup and gained complete control over Goguryeo. In response, Emperor Tang Taizong of China led a campaign against Goguryeo, in which the Gorguryeo forces were decimated by the Tang at the Battle of Mount Jupil. Taizong was later defeated at the Battle of Ansi and withdrew his forces from Goguryeo.[41][42][self-published source?] After the death of Tang Taizong, his son Emperor Tang Gaozong allied with the Korean kingdom of Silla and invaded Goguryeo again, but were forced to withdraw in 662.[43][44] However, Yeon Gaesomun died of a natural cause in 666 and Goguryeo was thrown into chaos and weakened by a succession struggle among his sons and younger brother, with his eldest son defecting to Tang and his younger brother defecting to Silla.[45][46] The Tang-Silla alliance conquered Goguryeo in 668. After the collapse of Goguryeo, Tang and Silla ended their alliance and fought over control of the Korean Peninsula. Silla succeeded in gaining control over most of the Korean Peninsula, while Tang gained control over Goguryeo's northern territories. However, 30 years after the fall of Goguryeo, a Goguryeo general by the name of Dae Joyeong founded the Korean-Mohe state of Balhae and successfully expelled the Tang presence from much of the former Goguryeo territories.

The southwestern Korean kingdom of Baekje was founded around modern-day Seoul by a Goguryeo prince, a son of the founder of Goguryeo.[47][48][self-published source?][49] Baekje absorbed all of the Mahan states and subjugated most of the western Korean peninsula (including the modern provinces of Gyeonggi, Chungcheong, and Jeolla, as well as parts of Hwanghae and Gangwon) to a centralised government; during the expansion of its territory, Baekje acquired Chinese culture and technology through maritime contacts with the Southern Dynasties. Baekje was a great maritime power;[50] its nautical skill, which made it the Phoenicia of East Asia, was instrumental in the dissemination of Buddhism throughout East Asia and continental culture to Japan.[51][52] Historic evidence suggests that Japanese culture, art, and language were influenced by the kingdom of Baekje and Korea itself;[25][53][54][55][56][57][58][59][60][61][62][63][excessive citations] Baekje also played an important role in transmitting advanced Chinese culture to the Japanese archipelago. Baekje was once a great military power on the Korean Peninsula, most notably in the 4th century during the rule of Geunchogo when its influence extended across the sea to Liaoxi and Shandong in China, taking advantage of the weakened state of Former Qin, and Kyushu in the Japanese archipelago;[64] however, Baekje was critically defeated by Gwanggaeto the Great and declined.[65]

Although later records claim that Silla was the oldest of the Three Kingdoms of Korea, it is now believed to have been the last kingdom to develop. By the 2nd century, Silla existed as a large state in the southeast, occupying and influencing its neighbouring city-states. In 562, Silla annexed the Gaya confederacy, which was located between Baekje and Silla. The Three Kingdoms of Korea often warred with each other and Silla was often dominated by Baekje and Goguryeo. Silla was the smallest and weakest of the three, but it used cunning diplomatic means to make opportunistic pacts and alliances with the more powerful Korean kingdoms, and eventually Tang China, to its great advantage.[66][67] In 660, King Muyeol ordered his armies to attack Baekje. General Kim Yu-shin, aided by Tang forces, conquered Baekje after defeating General Gyebaek at the Battle of Hwangsanbeol. In 661, Silla and Tang attacked Goguryeo but were repelled. King Munmu, son of Muyeol and nephew of General Kim Yu-shin, launched another campaign in 667 and Goguryeo fell in the following year.

North–South States Period

Beginning in the 6th century, Silla's power gradually extended across the Korean Peninsula. Silla first annexed the adjacent Gaya confederacy in 562. By the 640s, Silla formed an alliance with the Tang dynasty of China to conquer Baekje and later Goguryeo. After conquering Baekje and Goguryeo, Silla repulsed Tang China from the Korean peninsula in 676. Even though Silla unified most of the Korean Peninsula, most of the Goguryeo territories to the north of the Korean Peninsula were ruled by Balhae. Former Goguryeo general[68][69] or chief of Sumo Mohe[70][71][72] Dae Jo-yeong led a group of Goguryeo and Mohe refugees to the Jilin and founded the kingdom of Balhae, 30 years after the collapse of Goguryeo, as the successor to Goguryeo. At its height, Balhae's territories extended from southern Manchuria down to the northern Korean peninsula. Balhae was called the "Prosperous Country in the East".[73]

Later Silla carried on the maritime prowess of Baekje, which acted like the Phoenicia of medieval East Asia,[74] and during the 8th and 9th centuries dominated the seas of East Asia and the trade between China, Korea and Japan, most notably during the time of Jang Bogo; in addition, Silla people made overseas communities in China on the Shandong Peninsula and the mouth of the Yangtze River.[75][76][77][78] Later Silla was a prosperous and wealthy country,[79] and its metropolitan capital of Gyeongju[80] was the fourth largest city in the world.[81][82][83][84] Later Silla experienced a golden age of art and culture,[85][86][87][88] as evidenced by the Hwangnyongsa, Seokguram, and Emille Bell. Buddhism flourished during this time, and many Korean Buddhists gained great fame among Chinese Buddhists[89] and contributed to Chinese Buddhism,[90] including: Woncheuk, Wonhyo, Uisang, Musang,[91][92][93][94] and Kim Gyo-gak, a Silla prince whose influence made Mount Jiuhua one of the Four Sacred Mountains of Chinese Buddhism.[95][96][97][98][99]

Later Silla fell apart in the late 9th century, giving way to the tumultuous Later Three Kingdoms period (892–935), and Balhae was destroyed by the Khitans in 926. Goryeo unified the Later Three Kingdoms and received the last crown prince and much of the ruling class of Balhae, thus bringing about a unification of the two successor nations of Goguryeo.[100]

Goryeo dynasty

Goryeo was founded in 918 and replaced Silla as the ruling dynasty of Korea. Goryeo's land was at first what is now South Korea and about 1/3 of North Korea, but later on managed to recover most of the Korean peninsula. Momentarily, Goryeo advanced to parts of Jiandao while conquering the Jurchens, but returned the territories due to the harsh climate and difficulties in defending them. The name "Goryeo" (高麗) is a short form of "Goguryeo" (高句麗) and was first used during the time of King Jangsu. Goryeo regarded itself as the successor of Goguryeo, hence its name and efforts to recover the former territories of Goguryeo.[101][102][103][104] Wang Geon, the founder of Goryeo, was of Goguryeo descent and traced his ancestry to a noble Goguryeo clan.[105] He made Kaesong, his hometown, the capital.

During this period, laws were codified and a civil service system was introduced. Buddhism flourished and spread throughout the peninsula. The development of celadon industries flourished in the 12th and 13th centuries. The publication of the Tripitaka Koreana onto more than 80,000 wooden blocks and the invention of the world's first metal movable type in the 13th century attest to Goryeo's cultural achievements.[106][107][108][109][110][111]

Goryeo had to defend frequently against attacks by nomadic empires, especially the Khitans and the Mongols. Goryeo had a hostile relationship with the Khitans, because the Khitan Empire had destroyed Balhae, also a successor state of Goguryeo. In 993, the Khitans, who had established the Liao dynasty in 907, invaded Goryeo, demanding that it make amity with them. Goryeo sent the diplomat Sŏ Hŭi to negotiate, who successfully persuaded the Khitans to let Goryeo expand to the banks of the Amnok (Yalu) River, citing that in the past the land belonged to Goguryeo, the predecessor of Goryeo.[112] During the Goryeo–Khitan War, the Khitan Empire invaded Korea twice more in 1009 and 1018, but was defeated.

After defeating the Khitan Empire, which was the most powerful empire of its time,[113][114] Goryeo experienced a golden age that lasted a century, during which the Tripitaka Koreana was completed, and there were great developments in printing and publishing, promoting learning and dispersing knowledge on philosophy, literature, religion, and science; by 1100, there were 12 universities that produced famous scholars and scientists.[115][116]

Goryeo was invaded by the Mongols in seven major campaigns from the 1230s until the 1270s, but was never conquered.[117] Exhausted after decades of fighting, Goryeo sent its crown prince to the Yuan capital to swear allegiance to the Mongols; Kublai Khan accepted, and married one of his daughters to the Korean crown prince,[117] and the dynastic line of Goryeo continued to survive under the overlordship of the Mongol Yuan dynasty as a semi-autonomous vassal state and compulsory ally. The two nations became intertwined for 80 years as all subsequent Korean kings married Mongol princesses,[117] and the last empress of the Yuan dynasty was a Korean princess.[118]

In the 1350s, King Gongmin was free at last to reform the Goryeo government when the Yuan dynasty began to crumble. Gongmin had various problems that needed to be dealt with, which included the removal of pro-Mongol aristocrats and military officials, the question of land holding, and quelling the growing animosity between the Buddhists and Confucian scholars. During this tumultuous period, Goryeo momentarily conquered Liaoyang in 1356, repulsed two large invasions by the Red Turbans in 1359 and 1360, and defeated the final attempt by the Yuan to dominate Goryeo when General Ch'oe Yŏng defeated a Mongol tumen in 1364. During the 1380s, Goryeo turned its attention to the Wokou threat and used naval artillery created by Ch'oe Mu-sŏn to annihilate hundreds of pirate ships.

Joseon dynasty

In 1392, the general Yi Seong-gye overthrew the Goryeo dynasty after he staged a coup and defeated General Ch'oe Yŏng. Yi Seong-gye named his new dynasty Joseon and moved the capital from Kaesong to Hanseong (formerly Hanyang; modern-day Seoul) and built the Gyeongbokgung palace.[119] In 1394, he adopted Confucianism as the country's official ideology, resulting in much loss of power and wealth by the Buddhists. The prevailing philosophy of the Joseon dynasty was Neo-Confucianism, which was epitomised by the seonbi class, scholars who passed up positions of wealth and power to lead lives of study and integrity.

Joseon was a nominal tributary state of China but exercised full sovereignty,[120][121] and maintained the highest position among China's tributary states,[122][123] which also included countries such as the Ryukyu Kingdom, Vietnam, Burma, Brunei, Laos, Thailand,[124][125][126] and the Philippines, among others.[127][128] In addition, Joseon received tribute from Jurchens and Japanese until the 17th century,[129][130][131] and had a small enclave in the Ryukyu Kingdom that engaged in trade with Siam and Java.[132]

During the 15th and 16th centuries, Joseon enjoyed many benevolent rulers who promoted education and science.[133] Most notable among them was Sejong the Great (r. 1418–50), who personally created and promulgated Hangul, the Korean alphabet.[134] This golden age[133] saw great cultural and scientific advancements,[135] including in printing, meteorological observation, astronomy, calendar science, ceramics, military technology, geography, cartography, medicine, and agricultural technology, some of which were unrivaled elsewhere.[136] Joseon implemented a class system that consisted of yangban the noble class, jungin the middle class, yangin the common class, and cheonin the lowest class, which included occupations such as butchers, tanners, shamans, entertainers, and nobi, the equivalent of slaves, bondservants, or serfs.[137][138]

In 1592 and again in 1597, the Japanese invaded Korea; the Korean military at the time was unprepared and untrained, due to two centuries of peace on the Korean Peninsula.[139] Toyotomi Hideyoshi intended to conquer China and India[140] through the Korean Peninsula, but was defeated by strong resistance from the Righteous Army, the naval superiority of Admiral Yi Sun-sin and his turtle ships, and assistance from Wanli Emperor of Ming China. However, Joseon experienced great destruction, including a tremendous loss of cultural sites such as temples and palaces to Japanese pillaging, and the Japanese brought back to Japan an estimated 100,000–200,000 noses cut from Korean victims.[141] Less than 30 years after the Japanese invasions, the Manchus took advantage of Joseon's war-weakened state and invaded in 1627 and 1637, and then went on to conquer the destabilised Ming dynasty.

After normalising relations with the new Qing dynasty, Joseon experienced a nearly 200-year period of peace. Kings Yeongjo and Jeongjo led a new renaissance of the Joseon dynasty during the 18th century.[142][143]

In the 19th century, the royal in-law families gained control of the government, leading to mass corruption and weakening of the state, with severe poverty and peasant rebellions spreading throughout the country. Furthermore, the Joseon government adopted a strict isolationist policy, earning the nickname "the hermit kingdom", but ultimately failed to protect itself against imperialism and was forced to open its borders, beginning an era leading into Japanese imperial rule.

Korean Empire

Beginning in 1871, Japan began to exert more influence in Korea, forcing it out of China's traditional sphere of influence. As a result of the First Sino-Japanese War (1894–95), the Qing dynasty had to give up such a position according to Article 1 of the Treaty of Shimonoseki, which was concluded between China and Japan in 1895. That same year, Empress Myeongseong of Korea was assassinated by Japanese agents.[144]

In 1897, the Joseon dynasty proclaimed the Korean Empire (1897–1910). King Gojong became emperor. During this brief period, Korea had some success in modernising the military, economy, real property laws, education system, and various industries. Russia, Japan, France, and the United States all invested in the country and sought to influence it politically.

The Russians were pushed out of the fight for Korea following the conclusion of the Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905). Korea became a protectorate of Japan shortly afterwards. In Manchuria on 26 October 1909, An Jung-geun assassinated the former Resident-General of Korea, Itō Hirobumi, for his role in trying to force Korea into occupation.

Japanese annexation and occupation of Korea

In 1910, an already militarily occupied Korea was a forced party to the Japan–Korea Annexation Treaty. The treaty was signed by Lee Wan-Yong, who was given the General Power of Attorney by the Emperor. However, the Emperor is said to have not actually ratified the treaty according to Yi Tae-jin.[145] There is a long dispute whether this treaty was legal or illegal due to its signing under duress, threat of force and bribes.

Korean resistance to the brutal Japanese occupation[146][147][148] was manifested in the nonviolent March First Movement of 1919, during which 7,000 demonstrators were killed by Japanese police and military.[149] The Korean liberation movement also spread to neighbouring Manchuria and Siberia.

Over five million Koreans were conscripted for labour beginning in 1939,[150] and tens of thousands of men were forced into Japan's military.[151] Nearly 400,000 Korean labourers died.[152] Approximately 200,000 girls and women,[153] mostly from China and Korea, were forced into sexual slavery for the Japanese military.[154] In 1993, Japanese Chief Cabinet Secretary Yohei Kono acknowledged the terrible injustices faced by these euphemistically named "comfort women".[155][156]

During the Japanese annexation, the Korean language was suppressed in an effort to eradicate Korean national identity. Koreans were forced to take Japanese surnames, known as Sōshi-kaimei.[157] Traditional Korean culture suffered heavy losses, as numerous Korean cultural artefacts were destroyed[158] or taken to Japan.[159] To this day, valuable Korean artefacts can often be found in Japanese museums or among private collections.[160] One investigation by the South Korean government identified 75,311 cultural assets that were taken from Korea, 34,369 in Japan and 17,803 in the United States. However, experts estimate that over 100,000 artefacts actually remain in Japan.[159][161] Japanese officials considered returning Korean cultural properties, but to date[159] this has not occurred.[161] Both Koreas and Japan still dispute the ownership of the Dokdo islets, located east of the Korean Peninsula.[162]

There was significant emigration to the overseas territories of the Empire of Japan during the Japanese occupation period, including Korea.[163] By the end of World War II, there were over 850,000 Japanese settlers in Korea.[164] After World War II, most of these overseas Japanese repatriated to Japan.[165] Migrants who remained squatted in informal settlements.[166]

Division and conflict

In 1945, with the surrender of Japan, the United Nations developed plans for a trusteeship administration, the Soviet Union administering the peninsula north of the 38th parallel and the United States administering the south. The politics of the Cold War resulted in the 1948 establishment of two separate governments, North Korea and South Korea.

The aftermath of World War II left Korea partitioned along the 38th parallel on 2 September 1945, with the north under Soviet occupation and the south under US occupation supported by other allied states. Consequently, North Korea, a Soviet-style socialist republic was established in the north, and South Korea, a Western-style regime, was established in the south.

North Korea is a one-party state, now centred on Kim Il Sung's Juche ideology, with a centrally planned industrial economy. South Korea is a multi-party state with a capitalist market economy, alongside membership in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development and the Group of Twenty. The two states have greatly diverged both culturally and economically since their partition, though they still share a common traditional culture and pre-Cold War history.

Since the 1960s, the South Korean economy has grown enormously and the economic structure was radically transformed. In 1957, South Korea had a lower per capita GDP than Ghana,[167] and by 2008 it was 17 times as high as Ghana's.[b]

According to R. J. Rummel, forced labour, executions, and concentration camps were responsible for over one million deaths in North Korea from 1948 to 1987;[169] others have estimated 400,000 deaths in concentration camps alone.[170] Estimates based on the most recent North Korean census suggest that 240,000 to 420,000 people died as a result of the 1990s famine and that there were 600,000 to 850,000 unnatural deaths in North Korea from 1993 to 2008.[171] In South Korea, as guerrilla activities expanded, the South Korean government used strong measures against peasants, such as forcefully moving their families from guerrilla areas. According to one estimate, these measures resulted in 36,000 people killed, 11,000 people wounded, and 432,000 people displaced.[172]

Korean War

The Korean War broke out when Soviet-backed North Korea invaded South Korea, though neither side gained much territory as a result. The Korean Peninsula remained divided, the Korean Demilitarized Zone being the de facto border between the two states.

In June 1950 North Korea invaded the South, using Soviet tanks and weaponry. During the Korean War (1950–53) more than 1.2 million people died and the three years of fighting throughout the nation effectively destroyed most cities.[173] The war ended with an armistice agreement at approximately the Military Demarcation Line, but the two governments are officially still at war.

North and South Korea

In 2018, the leaders of North Korea and South Korea officially signed the Panmunjom Declaration, announcing that they will work to end the conflict.[174]

In November 2020, South Korea and China agreed to work together to mend South Korea's relationship with North Korea. During a meeting between President Moon and China's foreign minister, Wang Yi, Moon expressed his gratitude to China for its role in helping to foster peace in the Korean Peninsula. Moon was quoted telling Wang during their meeting that "[the South Korean] government will not stop efforts to put an end (formally) to war on the Korean Peninsula and achieve complete denuclearization and permanent peace together with the international community, including China."[175]

Geography

Korea consists of a peninsula and nearby islands located in East Asia. The peninsula extends southwards for about 1,100 km (680 mi) from continental Asia into the Pacific Ocean and is surrounded by the Sea of Japan to the east and the Yellow Sea (West Sea) to the west, the Korea Strait connecting the two bodies of water.[176][177] To the northwest, the Amnok River separates Korea from China and to the northeast, the Duman River separates it from China and Russia.[178] Notable islands include Jeju Island, Ulleung Island, Dokdo.

The southern and western parts of the peninsula have well-developed plains, while the eastern and northern parts are mountainous. The highest mountain in Korea is Mount Paektu (2,744 m), through which runs the border with China. The southern extension of Mount Paektu is a highland called Gaema Heights. This highland was mainly raised during the Cenozoic orogeny and partly covered by volcanic matter. To the south of Gaema Gowon, successive high mountains are located along the eastern coast of the peninsula. This mountain range is named Baekdu-daegan. Some significant mountains include Mount Sobaek or Sobaeksan (1,439 m), Mount Kumgang (1,638 m), Mount Seorak (1,708 m), Mount Taebaek (1,567 m), and Mount Jiri (1,915 m). There are several lower, secondary mountain series whose direction is almost perpendicular to that of Baekdu-daegan. They are developed along the tectonic line of Mesozoic orogeny and their directions are basically northwest.

Unlike most ancient mountains on the mainland, many important islands in Korea were formed by volcanic activity in the Cenozoic orogeny. Jeju Island, situated off the southern coast, is a large volcanic island whose main mountain, Mount Halla or Hallasan (1,950 m), is the highest in South Korea. Ulleung Island is a volcanic island in the Sea of Japan, the composition of which is more felsic than Jeju. The volcanic islands tend to be younger, the more westward.

Because the mountainous region is mostly on the eastern part of the peninsula, the main rivers tend to flow westwards. Two exceptions are the southward-flowing Nakdong River and Seomjin River. Important rivers running westward include the Amnok River, the Chongchon River, the Taedong River, the Han River, the Geum River, and the Yeongsan River. These rivers have vast flood plains and provide an ideal environment for wet-rice cultivation.

The southern and southwestern coastlines of the peninsula form a well-developed ria coastline, known as Dadohae-jin in Korean. This convoluted coastline provides mild seas, and the resulting calm environment allows for safe navigation, fishing, and seaweed farming. In addition to the complex coastline, the western coast of the Korean Peninsula has an extremely high tidal amplitude (at Incheon, around the middle of the western coast, the tide can get as high as 9 m). Vast tidal flats have been developing on the south and west coastlines.

Climate

Korea has a temperate climate with comparatively fewer typhoons than other countries in East Asia. Due to the peninsula's position, it has a unique climate influenced by Siberia in the north, the Pacific Ocean in the east and the rest of Eurasia in the west. The peninsula has four distinct seasons: spring, summer, autumn and winter.[179]

Spring

As influence from Siberia weakens, temperatures begin to increase while the high pressure begins to move away. If the weather is abnormally dry, Siberia will have more influence on the peninsula leading to wintry weather such as snow.[180]

Summer

During June at the start of the summer, there tends to be a lot of rain due to the cold and wet air from the Sea of Okhotsk and the hot and humid air from the Pacific Ocean combining. When these fronts combine, it leads to a so-called rainy season with often cloudy days with rain, which is sometimes very heavy. The hot and humid winds from the south west blow causing an increasing amount of humidity and this leads to the fronts moving towards Manchuria in China and thus there is less rain and this is known as midsummer; temperatures can exceed 30 °C (86 °F) daily at this time of year.

Autumn

Usually, high pressure is heavily dominant during autumn leading to clear conditions. Furthermore, temperatures remain high but the humidity becomes relatively low.

Winter

The weather becomes increasingly dominated by Siberia during winter and the jet stream moves further south causing a drop in temperature. This season is relatively dry with some snow falling at times.

Biodiversity

Animal life of the Korean Peninsula includes a considerable number of bird species and native freshwater fish. Native or endemic species of the Korean Peninsula include Korean hare, Korean water deer, Korean field mouse, Korean brown frog, Korean pine and Korean spruce. The Korean Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) with its forest and natural wetlands is a unique biodiversity spot, which harbours eighty-two endangered species. Korea once hosted many Siberian tigers, but as the number of people affected by the tigers increased, the tigers were killed in the Joseon dynasty and the Siberian tigers in the South Korea became extinct during the Japanese colonial era period. It has been confirmed that Siberian tigers are only on the side of North Korea now.

There are also approximately 3,034 species of vascular plants throughout the peninsula.

Economy

Science and technology

One of the best known artefacts of Korea's history of science and technology is the Cheomseongdae, a 9.4-meter high astronomical observatory built in 634.

The earliest known surviving Korean example of woodblock printing is The Great Dharani Sutra.[181] It is believed to have been printed in Korea in 750–51, which if correct, would make it older than the Diamond Sutra.

During the Goryeo period, metal movable type printing was invented by Ch'oe Yun-ŭi in 1234.[182][108][183][184][111][106] This invention made printing easier, more efficient and also increased literacy, which observed by Chinese visitors was seen to be so important where it was considered to be shameful to not be able to read.[185] The Mongol Empire later adopted Korea's movable type printing and spread as far as Central Asia. There is conjecture as to whether or not Ch'oe's invention had any influence on later printing inventions such as Gutenberg's Printing press.[186] When the Mongols invaded Europe they inadvertently introduced different kinds of Asian technology.[187]

During the Joseon period, the Turtle Ship was invented, which were covered by a wooden deck and iron with thorns,[188][189][190] as well as other weapons such as the bigyeokjincheolloe cannon (비격진천뢰, 飛擊震天雷) and the hwacha.

The Korean alphabet hangul was also invented during this time by King Sejong the Great.

Demographics

As of 2023[update], the combined population of the Koreas is about 77.9 million (South Korea: 51.7 million, North Korea: 26.1 million).[191][192] Korea is chiefly populated by a highly homogeneous ethnic group, the Koreans, who speak the Korean language.[193] The number of foreigners living in Korea has also steadily increased since the late 20th century, particularly in South Korea, where more than 1 million foreigners reside.[194] It was estimated in 2006 that only 26,700 of the old Chinese community now remain in South Korea.[195] However, in recent years, immigration from mainland China has increased; 624,994 persons of Chinese nationality have immigrated to South Korea, including 443,566 of ethnic Korean descent.[196] Small communities of ethnic Chinese and Japanese are also found in North Korea.[197]

| Rank | Name | Province | Pop. | Rank | Name | Province | Pop. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Seoul  Busan |

1 | Seoul | Seoul | 9,904,312 | 11 | Goyang | Gyeonggi | 990,073 |  Pyongyang  Incheon |

| 2 | Busan | Busan | 3,448,737 | 12 | Yongin | Gyeonggi | 971,327 | ||

| 3 | Pyongyang | Pyongyang | 3,255,288 | 13 | Seongnam | Gyeonggi | 948,757 | ||

| 4 | Incheon | Incheon | 2,890,451 | 14 | Bucheon | Gyeonggi | 843,794 | ||

| 5 | Daegu | Daegu | 2,446,052 | 15 | Cheongju | North Chungcheong | 833,276 | ||

| 6 | Daejeon | Daejeon | 1,538,394 | 16 | Hamhung | South Hamgyong | 768,551 | ||

| 7 | Gwangju | Gwangju | 1,502,881 | 17 | Ansan | Gyeonggi | 747,035 | ||

| 8 | Suwon | Gyeonggi | 1,194,313 | 18 | Chongjin | North Hamgyong | 667,929 | ||

| 9 | Ulsan | Ulsan | 1,166,615 | 19 | Jeonju | North Jeolla | 658,172 | ||

| 10 | Changwon | South Gyeongsang | 1,059,241 | 20 | Cheonan | South Chungcheong | 629,062 | ||

Language

Korean is the official language of both North and South Korea, and (along with Mandarin) of Yanbian Korean Autonomous Prefecture in Jilin Province, China. Worldwide, there are up to 80 million speakers of the Korean language. South Korea has around 50 million speakers while North Korea around 25 million. Other large groups of Korean speakers through Korean diaspora are found in China, the United States, Japan, former Soviet Union and elsewhere.

Modern Korean is written almost exclusively in the script of the Korean alphabet (known as Hangul in South Korea and Chosungul in China and North Korea), which was invented in the 15th century. Korean is sometimes written with the addition of some Chinese characters called Hanja; however, this is only occasionally seen nowadays.

Religion

Confucian tradition has dominated Korean thought, along with contributions by Buddhism, Taoism, and Korean Shamanism. Since the middle of the 20th century, however, Christianity has competed with Buddhism in South Korea, while religious practice has been suppressed in North Korea. Throughout Korean history and culture, regardless of separation; the influence of traditional beliefs of Korean Shamanism, Mahayana Buddhism, Confucianism and Taoism have remained an underlying religion of the Korean people as well as a vital aspect of their culture; all these traditions have coexisted peacefully for hundreds of years up to today despite strong Westernisation from Christian missionary conversions in the South[198][199][200] or the pressure from the Juche government in the North.[201][202]

According to 2005 statistics compiled by the South Korean government, about 46% of citizens profess to follow no particular religion. Christians account for 29.2% of the population (of which are Protestants 18.3% and Catholics 10.9%) and Buddhists 22.8%.[203] In North Korea, around 71.3% claim to be non-religious or atheists, 12.9% follow Cheondoism and 12.3% Korean Folk Religion, while Christians count for 2% of the population, and Buddhists as 1.5%.[204]

Islam in South Korea is practised by about 45,000 natives (about 0.09% of the population) in addition to some 100,000 foreign workers from Muslim countries.[205] While in North Korea it's estimated to be around 3000 Muslims, which is around 0.01% of the popultation.[206] The Ar-Rahman Mosque is the only mosque in DPRK, and it is located at the Iranian Embassy grounds in Pyongyyang.[207]

In 1993, the Korean Overseas Culture and Information Service estimated that around 1,600,000 people practice Korean new religions in both Korean countries.[208]

Education

The modern South Korean school system consists of six years in elementary school, three years in middle school, and three years in high school. Students are required to go to elementary and middle school, and do not have to pay for their education, except for a small fee called a "School Operation Support Fee" that differs from school to school. The Programme for International Student Assessment, coordinated by the OECD, ranks South Korea's science education as the third best in the world and being significantly higher than the OECD average.[209]

Although South Korean students often rank high on international comparative assessments, the education system is criticised for emphasising too much upon passive learning and memorisation. The South Korean education system is rather notably strict and structured as compared to its counterparts in most Western societies.

The North Korean education system consists primarily of universal and state funded schooling by the government. The national literacy rate for citizens 15 years of age and above is over 99 per cent.[210][211] Children go through one year of kindergarten, four years of primary education, six years of secondary education, and then on to universities. The most prestigious university in the DPRK is Kim Il Sung University. Other notable universities include Kim Chaek University of Technology, which focuses on computer science, Pyongyang University of Foreign Studies, which trains working level diplomats and trade officials, and Kim Hyong Jik University of Education, which trains teachers.

Culture

In ancient Chinese texts, Korea is referred to as "Rivers and Mountains Embroidered on Silk" (금수강산; 錦繡江山) and "Eastern Nation of Decorum" (동방예의지국; 東方禮儀之國).[214] Individuals are regarded as one year old when they are born, as Koreans reckon the pregnancy period as one year of life for infants, and age increments increase on New Year's Day rather than on the anniversary of birthdays. Thus, one born immediately before New Year's Day may only be a few days old in western reckoning, but two years old in Korea. Accordingly, a Korean person's stated age (at least among fellow Koreans) will be one or two years more than their age according to western reckoning. However, western reckoning is sometimes applied with regard to the concept of legal age; for example, the legal age for purchasing alcohol or cigarettes in the Republic of Korea is 19, which is measured according to western reckoning.

Literature

Korean literature written before the end of the Joseon dynasty is called "Classical" or "Traditional." Literature, written in Chinese characters (hanja), was established at the same time as the Chinese script arrived on the peninsula. Korean scholars were writing poetry in the classical Korean style as early as the 2nd century BCE, reflecting Korean thoughts and experiences of that time. Classical Korean literature has its roots in traditional folk beliefs and folk tales of the peninsula, strongly influenced by Confucianism, Buddhism and Taoism.

Modern literature is often linked with the development of hangul, which helped spread literacy from the aristocracy to the common people. Hangul, however, only reached a dominant position in Korean literature in the second half of the 19th century, resulting in a major growth in Korean literature. Sinsoseol, for instance, are novels written in hangul.

The Korean War led to the development of literature centered on the wounds and chaos of war. Much of the post-war literature in South Korea deals with the daily lives of ordinary people, and their struggles with national pain. The collapse of the traditional Korean value system is another common theme of the time.

Music

Traditional Korean music includes combinations of the folk, vocal, religious and ritual music styles of the Korean people. Korean music has been practised since prehistoric times.[215] Korean music falls into two broad categories. The first, Hyangak, literally means The local music or Music native to Korea, a famous example of which is Sujechon, a piece of instrumental music often claimed to be at least 1,300 years old.[216] The second, yangak, represents a more Western style.

Cuisine

Koreans traditionally believe that the taste and quality of food depend on its spices and sauces, the essential ingredients to making a delicious meal. Therefore, soybean paste, soy sauce, gochujang or red pepper paste and kimchi are some of the most important staples in a Korean household.

Korean cuisine was greatly influenced by the geography and climate of the Korean Peninsula, which is known for its cold autumns and winters, therefore there are many fermented dishes and hot soups and stews.

Korean cuisine is probably best known for kimchi, a side dish which uses a distinctive fermentation process of preserving vegetables, most commonly cabbage. Kimchi is said to relieve the pores on the skin, thereby reducing wrinkles and providing nutrients to the skin naturally. It is also healthy, as it provides necessary vitamins and nutrients. Gochujang, a traditional Korean sauce made of red pepper is also commonly used, often as pepper (chilli) paste, earning the cuisine a reputation for spiciness.

Bulgogi (roasted marinated meat, usually beef), galbi (marinated grilled short ribs), and samgyeopsal (pork belly) are popular main courses. Fish is also a popular commodity, as it is the traditional meat that Koreans eat. Meals are usually accompanied by a soup or stew, such as galbitang (stewed ribs) or doenjang jjigae (fermented bean paste soup). The center of the table is filled with a shared collection of sidedishes called banchan.

Other popular dishes include bibimbap, which literally means "mixed rice" (rice mixed with meat, vegetables, and red pepper paste), and naengmyeon (cold noodles).[217][218]

Instant noodles, or ramyeon, is a popular snack food. Koreans also enjoy food from pojangmachas (street vendors), which serve tteokbokki, rice cake and fish cake with a spicy gochujang sauce; gimbap, made of steamed white rice wrapped in dried green laver seaweed; fried squid; and glazed sweet potato. Soondae, a sausage made of cellophane noodles and pork blood, is widely eaten.

Additionally, some other common snacks include "Choco Pie", shrimp crackers, "bbeongtwigi" (puffed rice grains), and "nurungji" (slightly burnt rice). Nurungji can be eaten as it is or boiled with water to make a soup. Nurungji can also be eaten as a snack or a dessert.

Korea is unique among Asian countries in its use of metal chopsticks. Metal chopsticks have been discovered in archaeological sites belonging to the ancient Korean kingdoms of Goguryeo, Baekje and Silla.

Sports

North Korea and South Korea usually compete as two separate nations in international events. There are, however, a few examples of them having competed as one entity, under the name Korea.

While association football remains one of the most popular sports in South Korea, the martial art of taekwondo is considered to be the national sport. Baseball and golf are also popular. The board game Go, known in Korea as baduk, has also been popular for over a millennium, first arriving from China in the 5th century CE; baduk is played both casually and competitively.

Martial arts

Taekwon-Do

Taekwon-Do is Korea's most famous martial art and sport. It combines combat techniques, self-defence, sport and exercise. Taekwon-Do has become an official Olympic sport, starting as a demonstration event in 1988 (when South Korea hosted the Games in Seoul) and becoming an official medal event in 2000. The two major Taekwon-Do federations were founded in Korea. The two are the International Taekwon-Do Federation and the World Taekwondo Federation.

Hapkido

Hapkido is a modern Korean martial art with a grappling focus that employs joint locks, throws, kicks, punches and other striking attacks like attacks against pressure points. Hapkido emphasises circular motion, non-resisting movements and control of the opponent. Practitioners seek to gain advantage through footwork and body positioning to employ leverage, avoiding the pure use of strength against strength.

Ssireum

Ssireum is a traditional form of wrestling that has been practised in Korea for thousands of years, with evidence discovered from Goguryeo of Korea's Three Kingdoms Period (57 BCE to 688). Ssireum is the traditional national sport of Korea. During a match, opponents grip each other by sash belts wrapped around the waist and the thigh, attempting to throw their competitor to the sandy ground of the ring. The first opponent to touch the ground with any body part above the knee or to lose hold of their opponent loses the round.

Ssireum competitions are traditionally held twice a year, during the Dano Festival (the 5th day of the fifth lunar month) and Chuseok (the 15th day of the 8th lunar month). Competitions are also held throughout the year as a part of festivals and other events.

Taekkyon

Taekkyon is a traditional martial art, considered the oldest form of fighting technique of Korea. Practiced for centuries and especially popular during the Joseon period, two forms co-existed: one for practical use, the other for sport. This form was usually practised alongside Ssireum during festivals and competitions between villages. Nonetheless, Taekkyon almost disappeared during the Japanese Occupation and the Korean War.

Though lost in North Korea, Taekkyon has enjoyed a spectacular revival from the 1980s in South Korea. It is the only martial art in the world (with Ssireum) recognised as a National Treasure of South Korea and a UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage.

Comparison of North and South Korea

| Indicator | North Korea | South Korea |

|---|---|---|

| Formal name in English | Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK) | Republic of Korea (ROK) |

| Formal name | 조선민주주의인민공화국 Chosŏn Minjujuŭi Inmin Konghwaguk |

대한민국 Daehanminguk |

| Flag |  |

|

| Emblem |  |

|

| Capital | Pyongyang | Seoul |

| Official languages | Korean | |

| Official name for Korean alphabet (i.e., same script, different name) |

Chosŏn'gŭl | Hangul |

| Government | One-party state Hereditary dictatorship |

Representative democracy Presidential system |

| Leader | General Secretary of the Workers' Party of Korea |

President of South Korea |

| Formal declaration | 9 September 1948 | 15 August 1948 |

| Area | 120,540 km2 | 100,210 km2 |

| Population (2023 est.) | 26,160,821 | 51,784,059 |

| GDP total (2019 / 2023 est.) | $16 billion | $1.721 trillion |

| GDP/capita (2019 / 2023 est.) | $640 | $33,393 |

| Currency | Korean People's won (sign: ₩, ISO: KPW) | Korean Republic won (sign: ₩, ISO: KRW) |

| Calling code | +850 | +82 |

| Internet TLD | .kp | .kr |

| Drives on the | right | |

| Active military personnel | 1,106,000 | 639,000 |

| Military expenditure (2010/2022) | $10 billion | $46.4 billion |

See also

- Inter-Korean summits

- Korean name

- Korean natural farming

- Korean War

- List of Korean inventions and discoveries

- National Treasures of North Korea

- National Treasures of South Korea

- North Korea–South Korea relations

- Korean reunification

Notes

- ^ Kim Jong Un holds three concurrent positions: General Secretary of the Workers' Party, President of the State Affairs Commission and Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces.

- ^ $26,341 GDP for Korea, $1513 for Ghana.[168]

References

Citations

- ^ Castello-Cortes 1996, p. 498, South Korea.

- ^ Castello-Cortes 1996, p. 413, North Korea.

- ^ Bae, Kidong. 2002 Radiocarbon Dates from Palaeolithic Sites in Korea. Radiocarbon 44(2): 473–476.

- ^ 발해 유민 포섭. 우리역사넷 (in Korean). National Institute of Korean History. Archived from the original on 27 March 2019. Retrieved 13 March 2019.

- ^ a b "Korean". Oxford English Dictionary. Archived from the original on 7 October 2021. Retrieved 20 December 2013.

- ^ "youtube on 'Korea? Corea?'". YouTube. 12 January 2016. Archived from the original on 11 December 2021.

- ^ "Korea", Wiktionary, 7 June 2023, archived from the original on 13 June 2023, retrieved 13 June 2023

- ^ Haw, Stephen G. (2006). Marco Polo's China: A Venetian in the Realm of Khubilai Khan. Routledge. pp. 4–5. ISBN 9781134275427. Retrieved 29 September 2017.

- ^ a b c d Baxter, William & al. "Baxter–Sagart Old Chinese Reconstruction Archived 27 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine", pp. 43, 58 & 80. 20 February 2011. Retrieved 20 December 2013.

- ^ Till, Geoffrey; Bratton, Patrick (2012). Sea Power and the Asia-Pacific: The Triumph of Neptune?. Routledge. p. 145. ISBN 9781136627248. Retrieved 29 September 2017.

- ^ Seung-Yong, Yunn (1996). Religious culture in Korea. Hollym. p. 99. ISBN 9781565910843. Retrieved 29 September 2017.

- ^ 디지털 삼국유사 사전, 박물지 시범개발. 문화콘텐츠닷컴. Korea Creative Content Agency. Archived from the original on 19 November 2018. Retrieved 6 February 2017.

- ^ 이기환 (30 August 2017). [이기환의 흔적의 역사]국호논쟁의 전말 ... 대한민국이냐 고려공화국이냐. Kyunghyang Shinmun (in Korean). Archived from the original on 12 August 2019. Retrieved 2 July 2018.

- ^ Lee, Deok-il. [이덕일 사랑] 대~한민국. The Chosun Ilbo (in Korean). Archived from the original on 19 November 2018. Retrieved 2 July 2018.

- ^ First attested in the 13th-century Samguk yusa as 阿斯達 (MC Asjedat[9]). The name is credited to the 6th-century Book of Wei but does not appear in surviving passages.

- ^ Li, Jie (21 August 2002). "Some Discoveries of Fossils and Relics of Prehistoric Civilizations From Around the World". Pureinsight. Archived from the original on 12 October 2008. Retrieved 3 November 2009.

- ^ Vovin, Alexander (2017). "Origins of the Japanese Language". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Linguistics. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199384655.013.277. ISBN 978-0-19-938465-5.

- ^ Janhunen, Juha (2010). "RReconstructing the Language Map of Prehistorical Northeast Asia". Studia Orientalia (108).

... there are strong indications that the neighbouring Baekje state (in the southwest) was predominantly Japonic-speaking until it was linguistically Koreanized.

- ^ "Korea". Asian info. Archived from the original on 4 February 2012. Retrieved 3 November 2009.

- ^ Yi, Ki-baek (1984). A New History of Korea. Harvard University Press. pp. 23–24. ISBN 9780674615762. Retrieved 21 November 2016.

- ^ Walker, Hugh Dyson (2012). East Asia: A New History. AuthorHouse. p. 104. ISBN 9781477265161. Archived from the original on 18 August 2021. Retrieved 21 November 2016.[self-published source]

- ^ Roberts, John Morris; Westad, Odd Arne (2013). The History of the World. Oxford University Press. p. 443. ISBN 9780199936762. Archived from the original on 14 January 2023. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- ^ Gardner, Hall (27 November 2007). Averting Global War: Regional Challenges, Overextension, and Options for American Strategy. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 158–159. ISBN 9780230608733. Archived from the original on 17 April 2021. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- ^ de Laet, Sigfried J. (1994). History of Humanity: From the seventh to the sixteenth century. UNESCO. p. 1133. ISBN 9789231028137. Archived from the original on 14 January 2023. Retrieved 10 October 2016.

- ^ a b Walker, Hugh Dyson (20 November 2012). East Asia: A New History. AuthorHouse. pp. 6–7. ISBN 9781477265178. Retrieved 18 November 2016.[self-published source]

- ^ Tudor, Daniel (10 November 2012). Korea: The Impossible Country: The Impossible Country. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 9781462910229. Archived from the original on 14 January 2023. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- ^ Kotkin, Stephen; Wolff, David (4 March 2015). Rediscovering Russia in Asia: Siberia and the Russian Far East: Siberia and the Russian Far East. Routledge. ISBN 9781317461296. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- ^ Kim, Jinwung (2012). A History of Korea: From "Land of the Morning Calm" to States in Conflict. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. p. 35. ISBN 978-0253000781. Archived from the original on 14 January 2023. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- ^ Yi, Hyŏn-hŭi; Pak, Sŏng-su; Yun, Nae-hyŏn (2005). New history of Korea. Jimoondang. p. 201. ISBN 9788988095850. Archived from the original on 14 January 2023. Retrieved 29 July 2016. "He launched a military expedition to expand his territory, opening the golden age of Goguryeo."

- ^ Hall, John Whitney (1988). The Cambridge History of Japan. Cambridge University Press. p. 362. ISBN 9780521223522. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- ^ Embree, Ainslie Thomas (1988). Encyclopedia of Asian history. Scribner. p. 324. ISBN 9780684188997. Archived from the original on 28 March 2024. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- ^ Cohen, Warren I. (20 December 2000). East Asia at the Center: Four Thousand Years of Engagement with the World. Columbia University Press. p. 50. ISBN 9780231502511. Archived from the original on 4 December 2016. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- ^ Kim, Jinwung (5 November 2012). A History of Korea: From "Land of the Morning Calm" to States in Conflict. Indiana University Press. p. 35. ISBN 978-0253000781. Archived from the original on 14 January 2023. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

- ^ "Kings and Queens of Korea". KBS World Radio. Korea Communications Commission. Archived from the original on 28 August 2016. Retrieved 26 August 2016.

- ^ Walker, Hugh Dyson (20 November 2012). East Asia: A New History. AuthorHouse. p. 161. ISBN 9781477265178. Retrieved 8 November 2016.[self-published source]

- ^ White, Matthew (7 November 2011). Atrocities: The 100 Deadliest Episodes in Human History. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 78. ISBN 9780393081923. Archived from the original on 14 January 2023. Retrieved 8 November 2016.

- ^ Grant, Reg G. (2011). 1001 Battles That Changed the Course of World History. Universe Pub. p. 104. ISBN 9780789322333. Archived from the original on 24 January 2023. Retrieved 8 November 2016.

- ^ Bedeski, Robert (12 March 2007). Human Security and the Chinese State: Historical Transformations and the Modern Quest for Sovereignty. Routledge. p. 90. ISBN 9781134125975. Archived from the original on 14 January 2023. Retrieved 8 November 2016.

- ^ Yi, Ki-baek (1984). A New History of Korea. Harvard University Press. p. 47. ISBN 9780674615762. Archived from the original on 14 January 2023. Retrieved 29 July 2016. "Koguryŏ was the first to open hostilities, with a bold assault across the Liao River against Liao-hsi, in 598. The Sui emperor, Wen Ti, launched a retaliatory attack on Koguryŏ but met with reverses and turned back in mid-course. Yang Ti, the next Sui emperor, proceeded in 612 to mount an invasion of unprecedented magnitude, marshalling a huge force said to number over a million men. And when his armies failed to take Liao-tung Fortress (modern Liao-yang), the anchor of Koguryŏ's first line of defense, he had a nearly a third of his forces, some 300,000 strong, break off the battle there and strike directly at the Koguryŏ capital of P'yŏngyang. But the Sui army was lured into a trap by the famed Koguryŏ commander Ŭlchi Mundŏk, and suffered a calamitous defeat at the Salsu (Ch'ŏngch'ŏn) River. It is said that only 2,700 of the 300,000 Sui soldiers who had crossed the Yalu survived to find their way back, and the Sui emperor now lifted the siege of Liao-tung Fortress and withdrew his forces to China proper. Yang Ti continued to send his armies against Koguryŏ but again without success, and before long his war-weakened empire crumbled."

- ^ Nahm, Andrew C. (2005). A Panorama of 5000 Years: Korean History (Second revised ed.). Seoul: Hollym International Corporation. p. 18. ISBN 978-0930878689. "China, which had been split into many states since the early 3rd century, was reunified by the Sui dynasty at the end of the 6th century. Soon afterward, Sui China mobilized its army and invaded Koguryŏ. However, the people of Koguryŏ were united and able to repel the Chinese invasion. In 612, Sui troops invaded Korea again, but Koguryŏ forces fought bravely and destroyed Sui troops everywhere. General Ŭlchi Mundŏk of Koguryŏ completely wiped out some 300,000 Sui troops which came across the Yalu River in the battles near the Salsu River (now Ch'ŏngch'ŏn River) with his ingenious military tactics. Only 2,700 Sui troops were able to flee from Korea. The Sui dynasty, which wasted so much energy and manpower in aggressive wars against Koguryŏ, fell in 618."

- ^ Tucker, Spencer C. (23 December 2009). A Global Chronology of Conflict: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East [6 volumes]: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East. ABC-CLIO. p. 406. ISBN 9781851096725.

- ^ Walker, Hugh Dyson (20 November 2012). East Asia: A New History. AuthorHouse. p. 161. ISBN 9781477265178. Retrieved 4 November 2016.[self-published source]

- ^ Ring, Trudy; Watson, Noelle; Schellinger, Paul (12 November 2012). Asia and Oceania: International Dictionary of Historic Places. Routledge. p. 486. ISBN 9781136639791. Archived from the original on 14 January 2023. Retrieved 16 July 2016.

- ^ Injae, Lee; Miller, Owen; Jinhoon, Park; Hyun-Hae, Yi (15 December 2014). Korean History in Maps. Cambridge University Press. p. 29. ISBN 9781107098466. Archived from the original on 14 January 2023. Retrieved 17 July 2016.

- ^ Yi, Ki-baek (1984). A New History of Korea. Harvard University Press. p. 67. ISBN 9780674615762. Archived from the original on 14 January 2023. Retrieved 2 August 2016.

- ^ Kim, Djun Kil (30 May 2014). The History of Korea, 2nd Edition. ABC-CLIO. p. 49. ISBN 9781610695824. Retrieved 17 July 2016.

- ^ Pratt, Chairman Department of East Asian Studies Keith; Pratt, Keith; Rutt, Richard (16 December 2013). Korea: A Historical and Cultural Dictionary. Routledge. p. 135. ISBN 9781136793936. Retrieved 22 July 2016.

- ^ Yu, Chai-Shin (2012). The New History of Korean Civilization. iUniverse. p. 27. ISBN 9781462055593. Archived from the original on 24 January 2023. Retrieved 22 July 2016.[self-published source]

- ^ Kim, Jinwung (5 November 2012). A History of Korea: From "Land of the Morning Calm" to States in Conflict. Indiana University Press. p. 28. ISBN 978-0253000781. Retrieved 22 July 2016.

- ^ Ebrey, Patricia Buckley; Walthall, Anne; Palais, James B. (2006). East Asia: A Cultural, Social, and Political History. Houghton Mifflin. p. 123. ISBN 9780618133840. Archived from the original on 28 March 2024. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- ^ Kitagawa, Joseph (5 September 2013). The Religious Traditions of Asia: Religion, History, and Culture. Routledge. p. 348. ISBN 9781136875908. Archived from the original on 3 July 2023. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- ^ Ebrey, Patricia Buckley; Walthall, Anne; Palais, James B. (2013). East Asia: A Cultural, Social, and Political History, Volume I: To 1800. Cengage Learning. p. 104. ISBN 978-1111808150. Archived from the original on 24 January 2023. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- ^ Griffis, William Elliot (1885). Corea, Without and Within: Chapters on Corean History, Manners and Religion. Presbyterian Board of Publication. p. 251. Retrieved 25 September 2016.

Corea was not only the road by which the art of China reached Japan, but it is the original home of many of the art-ideas which the world believes to be purely Japanese..

- ^ Yayo, Metropolitan Museum of Art, archived from the original on 4 January 2020, retrieved 17 July 2011,

Metallurgy was also introduced from the Asian mainland during this time. Bronze and iron were used to make weapons, armor, tools, and ritual implements such as bells (dotaku)

- ^ Chon, Ho Chon. "Kitora Tomb Originates in Koguryo Murals". Choson Sinbo. No. 35. JP: Korea NP. Archived from the original on 26 February 2012.

- ^ "Yayoi", eMuseum, MNSU, archived from the original on 26 February 2011

- ^ "Japanese history: Jomon, Yayoi, Kofun". Japan guide. 9 June 2002. Archived from the original on 19 November 2018. Retrieved 21 May 2012.

- ^ "Asia Society: The Collection in Context". Asia society museum. Archived from the original on 19 September 2009. Retrieved 21 May 2012.

- ^ Pottery – MSN Encarta. Archived from the original on 29 October 2009. "The pottery of the Yayoi culture (c. 300 BCE – CE c. 250), made by a Mongol people who came from Korea to Kyūshū, has been found throughout Japan. "

- ^ "Kanji". Japan guide. 25 November 2010. Archived from the original on 10 May 2012. Retrieved 21 May 2012.

- ^ Noma, Seiroku (2003). The Arts of Japan: Late Medieval to Modern. Kodansha International. ISBN 978-4-7700-2978-2. Archived from the original on 15 February 2023. Retrieved 21 May 2012.

- ^ "Japanese Art and Its Korean Secret". Kenyon. 6 April 2003. Archived from the original on 9 July 2011. Retrieved 21 May 2012.

- ^ "Japanese Royal Tomb Opened to Scholars for First Time". National geographic. 28 October 2010. Archived from the original on 1 May 2008. Retrieved 21 May 2012.

- ^ A Brief History of Korea. Ewha Womans University Press. 1 January 2005. pp. 29–30. ISBN 9788973006199. Retrieved 21 November 2016.

- ^ Yu, Chai-Shin (2012). The New History of Korean Civilization. iUniverse. p. 27. ISBN 9781462055593. Archived from the original on 24 January 2023. Retrieved 21 November 2016.

- ^ Kim, Jinwung (2012). A History of Korea: From "Land of the Morning Calm" to States in Conflict. Indiana University Press. pp. 44–45. ISBN 978-0253000248. Archived from the original on 24 January 2023. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- ^ Wells, Kenneth M. (3 July 2015). Korea: Outline of a Civilisation. BRILL. pp. 18–19. ISBN 9789004300057. Archived from the original on 24 January 2023. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- ^ Old records of Silla 新羅古記(Silla gogi): ... 高麗舊將祚榮

- ^ Rhymed Chronicles of Sovereigns 帝王韻紀(Jewang ungi): ... 前麗舊將大祚榮

- ^ Solitary Cloud 孤雲集(Gounjib): ... 渤海之源流也句驪未滅之時本爲疣贅部落靺羯之屬寔繁有徒是名栗末小蕃甞逐句驪, 內徙其首領乞四羽及大祚榮等至武后臨朝之際自營州作孼而逃輒據荒丘始稱振國時有句驪遺燼勿吉雜流梟音則嘯聚白山鴟義則喧張黑姶與契丹濟惡旋於突厥通謀萬里耨苗累拒渡遼之轍十年食葚晚陳降漢之旗.

- ^ Solitary Cloud 孤雲集(Gounjip): ... 其酋長大祚榮, 始受臣藩第五品大阿餐之秩

- ^ Comprehensive Institutions 通典(Tongdian): ... 渤海夲栗末靺鞨至其酋祚榮立國自號震旦, 先天中 玄宗王子始去靺鞨號專稱渤海

- ^ Injae, Lee; Miller, Owen; Jinhoon, Park; Hyun-Hae, Yi (15 December 2014). Korean History in Maps. Cambridge University Press. pp. 64–65. ISBN 978-1107098466. Archived from the original on 24 January 2023. Retrieved 24 February 2017.

- ^ Kitagawa, Joseph (5 September 2013). The Religious Traditions of Asia: Religion, History, and Culture. Routledge. p. 348. ISBN 978-1136875908. Archived from the original on 3 July 2023. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- ^ Gernet, Jacques (31 May 1996). A History of Chinese Civilization. Cambridge University Press. p. 291. ISBN 978-0521497817. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

Korea held a dominant position in the north-eastern seas.

- ^ Reischauer, Edwin Oldfather (1955). Ennins Travels in Tang China. John Wiley & Sons Canada, Limited. pp. 276–283. ISBN 978-0471070535. Archived from the original on 28 March 2024. Retrieved 21 July 2016. "From what Ennin tells us, it seems that commerce between East China, Korea and Japan was, for the most part, in the hands of men from Silla. Here in the relatively dangerous waters on the eastern fringes of the world, they performed the same functions as did the traders of the placid Mediterranean on the western fringes. This is a historical fact of considerable significance but one which has received virtually no attention in the standard historical compilations of that period or in the modern books based on these sources. . . . While there were limits to the influence of the Koreans along the eastern coast of China, there can be no doubt of their dominance over the waters off these shores. . . . The days of Korean maritime dominance in the Far East actually were numbered, but in Ennin's time the men of Silla were still the masters of the seas in their part of the world."

- ^ Kim, Djun Kil (30 May 2014). The History of Korea, 2nd Edition. ABC-CLIO. p. 3. ISBN 978-1610695824.

- ^ Seth, Michael J. (2006). A Concise History of Korea: From the Neolithic Period Through the Nineteenth Century. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 65. ISBN 978-0742540057. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- ^ MacGregor, Neil (2011). A History of the World in 100 Objects. Penguin UK. ISBN 978-0141966830. Retrieved 30 September 2016.

- ^ Chŏng, Yang-mo; Smith, Judith G.; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, N.Y.) (1998). Arts of Korea. Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 230. ISBN 978-0870998508. Retrieved 30 September 2016.

- ^ Adams, Edward B. (1989). "The Legacy of Kyongju". The Rotarian. Vol. 154, no. 4. Rotary International. p. 28. ISSN 0035-838X. Retrieved 19 December 2018.

- ^ Ross, Alan (17 January 2013). After Pusan. Faber & Faber. ISBN 978-0571299355. Retrieved 30 September 2016.

- ^ Mason, David A. "Gyeongju, Korea's treasure house". Korea.net. Korean Culture and Information Service. Archived from the original on 3 October 2016. Retrieved 30 September 2016.

- ^ Adams, Edward Ben (1990). Koreaʾs Pottery Heritage. Vol. 1. Seoul International Pub. House. p. 53. ISBN 9788985113069. OCLC 1014620947. Archived from the original on 28 March 2024. Retrieved 19 December 2018.

- ^ DuBois, Jill (2004). Korea. Marshall Cavendish. p. 22. ISBN 978-0761417866. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

golden age of art and culture.

- ^ Randel, Don Michael (28 November 2003). The Harvard Dictionary of Music. Harvard University Press. p. 273. ISBN 978-0674011632. Archived from the original on 29 November 2023. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- ^ Hopfner, Jonathan (10 September 2013). Moon Living Abroad in South Korea. Avalon Travel. p. 21. ISBN 978-1612386324. Archived from the original on 11 November 2022. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- ^ Kim, Djun Kil (30 January 2005). The History of Korea. ABC-CLIO. p. 47. ISBN 978-0313038532. Retrieved 30 September 2016.

- ^ Mun, Chanju; Green, Ronald S. (2006). Buddhist Exploration of Peace and Justice. Blue Pine Books. p. 147. ISBN 978-0977755301. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- ^ McIntire, Suzanne; Burns, William E. (25 June 2010). Speeches in World History. Infobase Publishing. p. 87. ISBN 978-1438126807. Archived from the original on 11 November 2022. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- ^ Buswell, Robert E. Jr.; Lopez, Donald S. Jr. (24 November 2013). The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism. Princeton University Press. p. 187. ISBN 978-1400848058. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- ^ Poceski, Mario (13 April 2007). Ordinary Mind as the Way: The Hongzhou School and the Growth of Chan Buddhism. Oxford University Press. p. 24. ISBN 978-0198043201. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- ^ Wu, Jiang; Chia, Lucille (15 December 2015). Spreading Buddha's Word in East Asia: The Formation and Transformation of the Chinese Buddhist Canon. Columbia University Press. p. 155. ISBN 978-0231540193. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- ^ Wright, Dale S. (25 March 2004). The Zen Canon: Understanding the Classic Texts. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199882182. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- ^ Su-il, Jeong (18 July 2016). The Silk Road Encyclopedia. Seoul Selection. ISBN 978-1624120763. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- ^ Nikaido, Yoshihiro (28 October 2015). Asian Folk Religion and Cultural Interaction. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. p. 137. ISBN 978-3847004851. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- ^ Leffman, David; Lewis, Simon; Atiyah, Jeremy (2003). China. Rough Guides. p. 519. ISBN 978-1843530190. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- ^ Leffman, David (2 June 2014). The Rough Guide to China. Penguin. ISBN 978-0241010372. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- ^ DK Eyewitness Travel Guide: China. Penguin. 21 June 2016. p. 240. ISBN 978-1465455673. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- ^ Lee, Ki-Baik (1984). A New History of Korea. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 103. ISBN 978-0674615762.

When Parhae perished at the hands of the Khitan around this same time, much of its ruling class, who were of Koguryŏ descent, fled to Koryŏ. Wang Kŏn warmly welcomed them and generously gave them land. Along with bestowing the name Wang Kye ("Successor of the Royal Wang") on the Parhae crown prince, Tae Kwang-hyŏn, Wang Kŏn entered his name in the royal household register, thus clearly conveying the idea that they belonged to the same lineage, and also had rituals performed in honor of his progenitor. Thus Koryŏ achieved a true national unification that embraced not only the Later Three Kingdoms but even survivors of Koguryŏ lineage from the Parhae kingdom.

- ^ Rossabi, Morris (20 May 1983). China Among Equals: The Middle Kingdom and Its Neighbors, 10th–14th Centuries. University of California Press. p. 323. ISBN 9780520045620. Retrieved 1 August 2016.

- ^ Yi, Ki-baek (1984). A New History of Korea. Harvard University Press. p. 103. ISBN 9780674615762. Archived from the original on 14 January 2023. Retrieved 20 October 2016.