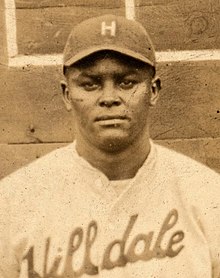

Biz Mackey

James Raleigh "Biz" Mackey (July 27, 1897 – September 22, 1965) was an American catcher and manager in Negro league baseball. He played for the Indianapolis ABCs, New York Lincoln Giants, Hilldale Daisies, Philadelphia Royal Giants, Philadelphia Stars, Washington / Baltimore Elite Giants, and Newark Dodgers / Eagles.

Mackey was regarded as black baseball's premier catcher in the late 1920s and early 1930s. His superior defense and outstanding throwing arm were complemented by batting skill which placed him among the Negro leagues' all-time leaders in total bases, runs batted in and slugging percentage, while hitting over .300 for his career. Mackey was elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 2006.

Baseball career

[edit]Mackey was born in Eagle Pass, Texas, to a sharecropping family that included two brothers.[3] He began playing baseball with his brothers on the Luling Oilers, a Prairie League team, in 1916 in his hometown of Luling. He joined the professional San Antonio Black Aces two years later. When the team folded in 1920, his contract was sold to the Indianapolis ABCs in time for the Negro National League's first season. After three years under manager C. I. Taylor, in which he hit .315, .317, and .344, he was picked up by Hilldale when the Eastern Colored League was organized in 1923.

In his first season with Hilldale, Mackey batted .423, winning the ECL batting title and pacing the team to the pennant, and followed with eight consecutive seasons batting .308 or better. In 1924, he finished third in the batting race as Hilldale repeated as champions, but lost to the Kansas City Monarchs 5 games to 4 in the first Negro League World Series with Mackey playing third base. At first platooning behind the plate with the aging Louis Santop, while also sharing time at shortstop with Pop Lloyd and Jake Stephens, he took over the full-time catching job in 1925. In that year's Negro League World Series, Mackey helped Hilldale to the title over the Monarchs with a .360 average. He drove in the lead run in the 11th inning of the first game, which Hilldale won in 12 innings. After scoring the winning run in a 2–1 victory in Game 5, his three hits in the deciding Game 6 clinched the title.

Mackey's barnstorming tours included a highly successful trip to Japan in 1927, during which he became the first player to hit a home run out of Meiji Shrine Stadium, doing so in three straight games. He was particularly well received on the tour and made later trips to Japan in 1934 and 1935. In 1931, he won his second batting title with a .359 average, as Hilldale also finished with the best record among eastern teams.

In voting for the first East–West All-Star Game in 1933, Mackey was selected at catcher over the young Josh Gibson, batting cleanup. He played in three more All-Star Games by 1938. In 1934, he batted only .299, as the Philadelphia Stars' won the NNL second-half pennant, but had a good postseason, batting .368 and driving in the first run of a 2–0 victory in Game 7 to defeat the Chicago American Giants four games to three.

By 1937, Mackey was managing the Baltimore Elite Giants, where he began mentoring 15-year-old Roy Campanella in the fine points of catching. Campanella later recalled:

- "In my opinion, Biz Mackey was the master of defense of all catchers. When I was a kid in Philadelphia, I saw both Mackey and Mickey Cochrane in their primes, but for real catching skills, I don't think Cochrane was the master of defense that Mackey was. When I went under his direction in Baltimore, I was 15 years old. I gathered quite a bit from Mackey, watching how he did things, how he blocked low pitches, how he shifted his feet for an outside pitch, how he threw with a short, quick, accurate throw without drawing back. I got all this from Mackey at a young age."

Mackey joined the Newark Eagles in 1939, replaced Dick Lundy as manager a year later, and continued his work with young players such as Monte Irvin, Larry Doby, and Don Newcombe. When Doby joined the Cleveland Indians of the American League in 1947, it was Mackey who recommended moving him from second base to center field.

Personality conflicts with Newark owner Effa Manley led to Mackey's departure from play after the 1941 season, moving to Los Angeles. While there, he worked at North American Aviation during World War II. He returned to the Eagles in 1945 when Manley had a conflict with his replacement, Willie Wells.[4] Mackey managed the team in 1946 as the Eagles won the Negro League World Series four games to three, again over the Monarchs, who featured pitcher Satchel Paige. Even in his forties, Mackey was still an effective player – he batted .307 in 1945, and appeared in the 1947 All-Star Game at age 50. When the Eagles moved to Houston in 1950, he retired from baseball following the season.

Later life

[edit]In the 1950s, Mackey moved to Los Angeles and began working as a forklift operator. In 1952, he was selected by a Pittsburgh Courier poll as the Negro leagues' greatest catcher, ahead of Josh Gibson. Mackey received more attention on May 7, 1959, when Campanella was honored at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum following his paralysis from a car accident. Mackey was introduced to the crowd of over 93,000 for an exhibition game between the Los Angeles Dodgers and New York Yankees.

Mackey lived in Los Angeles until his death in 1965. He is buried in that city's Evergreen Cemetery.[5] Through the 1990s, reference sources widely reported his death as having occurred in 1959; this seems to have resulted from Campanella's recollection in John B. Holway's 1988 book Blackball Stars that Mackey "passed away right after" the Coliseum event, an apparent error that Campanella repeated in other interviews. In 2006, Mackey was elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

Mackey's grandson Riley Odoms played 12 seasons for the National Football League's Denver Broncos.

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "MLB officially designates the Negro Leagues as 'Major League'". MLB.com. December 16, 2020. Retrieved November 29, 2024.

- ^ "With Taber on Mound Chester Beats Hilldale" Chester Times, Chester, PA, Tuesday, July 29, 1924, Page 6, Column 1

- ^ Santoliquito, Joseph (February 16, 2007). "Great-nephew keeps legacy alive for "Biz" Mackey". ESPN.com. Retrieved November 3, 2013.

- ^ Rainey, Chris. "Biz Mackey – Society for American Baseball Research". Retrieved January 10, 2024.

- ^ Biz Mackey's Grave Archived January 24, 2013, at the Wayback Machine Thedeadballera.com

- Holway, John B. (1988). Blackball Stars: Negro League Pioneers. Westport, Connecticut: Meckler Books. ISBN 0-88736-094-7.

- Riley, James A. (1994). The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues. New York: Carroll & Graf. ISBN 0-7867-0065-3.

- Holway, John (2001). The Complete Book of Baseball's Negro Leagues: The Other Half of Baseball History. Fern Park, Florida: Hastings House. ISBN 0-8038-2007-0.

- Martin, Douglas D. (1987). Biographical Dictionary of American Sports: Baseball. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-23771-9.

- Brockenbury, L.I. "Brock" (September 30, 1965). "Tying the Score". Los Angeles Sentinel, p. 28.

External links

[edit]- Biz Mackey at the Baseball Hall of Fame

- Career statistics from MLB, or Baseball Reference and Baseball-Reference Black Baseball stats and Seamheads

- Biz Mackey managerial career statistics at Baseball-Reference.com and Seamheads

- Negro League Baseball Players Association

- Biz Mackey at Find a Grave

- 1897 births

- 1965 deaths

- African-American baseball players

- National Baseball Hall of Fame inductees

- New York Lincoln Giants players

- Indianapolis ABCs players

- Hilldale Club players

- Baltimore Elite Giants players

- Baltimore Black Sox players

- Homestead Grays players

- Newark Eagles players

- Philadelphia Stars players

- Pittsburgh Crawfords players

- St. Louis Giants players

- Negro league baseball managers

- Baseball players from Maverick County, Texas

- People from Eagle Pass, Texas

- Burials at Evergreen Cemetery, Los Angeles