Concerto delle donne

The concerto delle donne[a] (lit. 'consort of ladies') was an ensemble of professional female singers of late Renaissance music in Italy. The term usually refers to the first and most influential group in Ferrara, which existed between 1580 and 1597.[b] Renowned for their technical and artistic virtuosity, the Ferrarese group's core members were the sopranos Laura Peverara, Livia d'Arco and Anna Guarini.

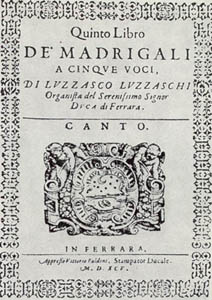

The Duke of Ferrara Alfonso II d'Este founded a group of mostly female singers for his chamber music series, musica secreta (lit. 'secret music'). These singers were exclusively noble women, such as Lucrezia and Isabella Bendidio. In 1580, Alfonso formally established the concerto delle donne for both his wife Margherita Gonzaga d'Este and reasons of prestige. The new group included professional singers of upper-class, but not noble, backgrounds, under the direction of the composers Luzzasco Luzzaschi and Ippolito Fiorini. Their signature style of florid, highly ornamented singing brought prestige to Ferrara and inspired composers of the time such as Lodovico Agostini, Carlo Gesualdo and Claudio Monteverdi.

The concerto delle donne revolutionized the role of women in professional music, and continued the tradition of the Este court as a musical center. Word of the ladies' ensemble spread across Italy, inspiring imitations in the courts of the Medici and Orsini. The founding of the concerto delle donne was among the most important events in the secular music in the late sixteenth century Italy. The musical innovations established in the court were important in the development of the madrigal, and eventually the seconda pratica.

Background

[edit]Northern Italy was a leading center of Renaissance music, which broadly covered the 15th and 16th centuries of Europe.[4] Regional courts, ruled by competing families—such as the Este, Gonzaga, and Medici—patronized secular music immensely, commissioning compositions and forming large ensembles.[5] Although the frottola style held early popularity, it was quickly overtaken by the madrigal in the 1520s.[6] The madrigal became the most important secular genre of 16th-century Italy, and possibly the entire Renaissance; according to J. Peter Burkholder, "through the madrigal, Italy became the leader in European music for the first time in history".[6] Unlike the frottola, composed exclusively by native Italians, the first leading madrigal composers were foreign Franco-Flemish musicians, referred to as Oltremontani (those from lit. '"over the mountains"'), such as Philippe Verdelot and Jacques Arcadelt.[7][8]

At the court in Ferrara, the Duke Alfonso II d'Este formed a group of mostly female singers by at least 1577.[9][10] They performed madrigals within the context of the Duke's ongoing musica secreta (lit. 'secret music'), a regular series of chamber music concerts performed for a private audience.[11][12] Although it is uncertain whether the group's members were amateur or professional musicians, they were noblewomen and would have attended court regardless.[10] These singers included sisters Lucrezia and Isabella Bendidio, as well as Leonora Sanvitale, and Vittoria Bentivoglio.[10] The professional bass singer Giulio Cesare Brancaccio also joined the ensemble.[10]

Formation

[edit]The Duke formally established the concerto delle donne[a] (lit. 'consort of ladies') in 1580.[13] He did not announce the creation of a new professional, all-female ensemble; instead, the group infiltrated and gradually dominated the musica secreta concerts.[14][15] This ensemble was created by the Duke in part to amuse his young new wife, Margherita Gonzaga d'Este who was musically-inclined herself, and in part to help the Duke achieve his artistic goals for the court.[16][17] Margherita's influence on the church through her brother-in-law, the cardinal Luigi d'Este, allowed the concerto to use church assets such as the San Vito convent in Ferrara.[18] The first recorded performance by the professional ladies was on 20 November 1580; Brancaccio joined the new group the next month.[10] By the 1581 carnival season, they were performing together regularly.[19]

This new "consort of ladies" was viewed as an extraordinary and novel phenomenon; most witnesses did not connect the concerto delle donne with the earlier group of ladies from the 1570s.[20] However, modern musicologists now view the earlier group as a crucial part of the creation and development of the social and vocal genre of the concerto delle donne.[20][14] The culture at the Italian courts of that time had a political dimension, as families aimed to present their greatness by non-violent means.[21]

Roster and duties

[edit]The most prominent member of the new ensemble was Laura Peverara, whose musical abilities prompted the Duke to specifically ask the Duchess to bring her from Mantua as part of her retinue.[15] She was particularly lauded for her skill in accompanied solo singing.[22] Peverara was joined by Livia d'Arco and Anna Guarini, daughter of the prolific poet Giovanni Battista Guarini.[10] The latter wrote poems for many of the madrigals which were performed by the ensemble,[23] and wrote texts for the balletto delle donne dances.[24] The well-known singer Tarquinia Molza was involved with the group, but modern scholars disagree on whether she sang with them or was solely as an advisor and instructor.[25][26][c] Whether Molza ever performed with them or not, she was ousted from any role in the group after her affair with the composer Giaches de Wert came to light in 1589.[27] After the dismissal of Brancaccio for insubordination in 1583, no more permanent male members of the musica secreta were hired;[15] however, the ensemble occasionally sang with male singers.[13]

The singers of the concerto delle donne were officially ladies-in-waiting of the Duchess Margherita, but were hired primarily as singers.[10][16] Despite their upper-class background, the singers would not have been welcomed into the court's inner circle had they not been such skilled performers.[28] D'Arco belonged to the nobility, but a minor family only. Peverara was the daughter of a wealthy merchant, and Molza came from a prominent family of artists.[29] The musicologist Thomasin LaMay posits that the women of the concerti delle donne provided sexual favors for members of the court,[30] but there is no evidence for this, and the circumstances of their marriages and dowries argues against this interpretation. The women were paid salaries and received other benefits, such as dowries and apartments in the ducal palace. Peverara received 300 scudi a year and lodging in the ducal palace for herself, her husband, and her mother – as well as a dowry of 10,000 scudi upon her marriage.[31]

The new singers played instruments, including the lute, harp, and viol,[32] but focused their energies on developing vocal virtuosity.[33] This skill became highly prized in the mid-sixteenth century, beginning with basses like Brancaccio, but by the end of the century virtuosic bass singing went out of style, and higher voices came into vogue.[34] The composer Luzzasco Luzzaschi directed and wrote music to showcase the ensemble,[32][35] and accompanied them on the harpsichord. The composer and lutenist Ippolito Fiorini was the maestro di cappella, in charge of the entire court's musical activities.[36] In addition to his duties to the overall court, Fiorini accompanied the concerto on the lute.[37]

Despite having married three times in the hopes of producing an heir, Alfonso II died in 1597 without issue, legitimate or otherwise. His cousin Cesare inherited the Duchy, but the city of Ferrara, which was legally a Papal fief, was annexed to the Papal States in 1598 through a combination of "firm diplomacy and unscrupulous pressure" by Pope Clement VIII.[11][38] The Este court had to abandon Ferrara in disarray and its music establishment was disbanded.[39] While the existence of the concerto delle donne was widely known, its detailed history was largely lost, dispersed between archival records,[1] until the beginning 20th century when the Italian literature critic Angelo Solerti drew attention to Ferrara's 16th century court culture.[40]

Music

[edit]Performance

[edit]The concerto delle donne transformed the musica secreta series. In the past, performers and audience members would alternate roles,[41] as the gatherings were "social music for the enjoyment of the singers themselves".[13] During the ascendancy of the concerto delle donne the roles within the musica secreta became fixed, resulting in "concert music for the pleasure of an audience".[13] The performances had a restricted audience; only selected dignitaries and few courtiers saw the concerto delle donne;[42] one such dignitary may have been the Russian ambassador Istoma Shevrigin, in 1581.[43]

The performers were thoroughly coached and rehearsed in their work, down to all hand gestures and facial movements.[44] The women performed up to six hours a day, either singing their own florid repertoire from memory, sight-reading from partbooks, or participating in the balletti as singers and dancers.[45] The ladies' musical duties included performing with the duchess' balletto delle donne, a group of female dancers who frequently crossdressed.[46][47]

Aside from Brancaccio, all the singers in the concerto were female sopranos.[48] There is no evidence that the ensemble used falsettists.[49] This fact is surprising, considering that castrati were shortly to become the biggest stars of a new art form, opera.[50] In 1607, Monteverdi's influential L'Orfeo featured four castrato roles out of a cast of nine, showing the new dominance of this vocal type.[51][d] It also contrasts with the court of Margherita's father, where Guglielmo Gonzaga actively sought out eunuchs.[53]

The elite, hand-selected audience members favored with admission to performances by the concerto delle donne demanded diversions and entertainment beyond the pleasures of beautiful music alone. During the concerts, members of the concerto's audience would sometimes play cards. The ambassador of the Grand Duke of Tuscany Orazio Urbani, having waited several years to see the concerto, complained that he was forced not only to play cards, distracting him from the performance, but also simultaneously admire and praise the women's music to their patron Alfonso.[54] After at least one concert, to continue the entertainment, a dwarf couple danced.[55] Alfonso was not as interested in these peripheral entertainments; in one instance he excused himself from the party to go sit under a tree to listen to the concerto, and follow along with the madrigal texts and musical scores, which were made available to listeners.[55]

Style

[edit]The greatest musical innovation of the concerto delle donne was its departure from one voice singing diminutions above an instrumental accompaniment to two or three highly ornamented voices singing varying diminutions at once.[56] Such ornaments were meticulously notated by the composers, leaving a detailed record of the concerto delle donne's performance practice.[57] Although traditionally such ornaments were improvised in performance, notation was used to coordinate and rehearse the multiple voices; the singers may have continued improvised diminutions in their solo repertoire.[58]

Specific ornaments used by the concerto delle donne, mentioned in a source from 1581, were such popular sixteenth-century devices as passaggi (division of a long note into many shorter notes, usually stepwise), cadenze (decoration of the penultimate note, sometimes quite elaborate), and tirate (rapid scales). Accenti (connection of two longer notes, using dotted rhythms), a staple of early Baroque music, are absent from the list.[54] In 1592 Giulio Caccini claimed that Alfonso asked him to teach his ladies the new accenti and passaggi styles.[59][60]

Repertoire

[edit]

Many Italian Renaissance composers wrote music either inspired by the concerto delle donne or specifically for them. Between 1581 and 1586 especially, Alfonso's court saw its most "vibrant and culturally productive period, during which its literary and musical talents were focused most keenly on providing repertoire for the ladies’ performances, both in private and as part of court spectacle".[61]

The output of the ducal printer, Vittorio Baldini, consisted largely of music written for the concerto delle donne.[62] Baldini's first publication for the Duke was Il lauro secco (1582), which was followed by Il lauro verde (1583), both containing music by the leading composers of Rome and Northern Italy.[63] Music in honor of the concerto was printed as far away as Venice, with Paolo Virchi's First Book à 5, published by Giacomo Vincenti and Ricciardo Amadino containing the madrigal which begins SeGU'ARINAscer LAURA e prenda LARCO / Amor soave e dolce / Ch'ogni cor duro MOLCE.[64] This capitalization is in the original, clearly spelling out the equivalent of the names Anna Guarini, Laura Peverara, Livia d'Arco, and Tarquinia Molza.[64]

Musically, their repertoire was written to display the skill of the upper-voiced singers; oftentimes lower static voices accompanied them in contrast.[2] Such works are characterized by a high tessitura, a virtuosic and florid style, and a wide vocal range.[65] There were two separate styles of madrigals written for and inspired by the concerto delle donne. The first is the "luxuriant" style of the 1580s, which set the poetry of Ferrarese natives—such as Tasso and G.B. Guarini—which were generally short and witty with single sections.[66] The second is music in the style of the seconda pratica, written in the 1590s, treated harmony with more freedom than the preceding prima pratica style .[67]

Specific personalities

[edit]

The chief composer for the concerto delle donne was their director, Luzzasco Luzzaschi,[68] who wrote works in both the "luxuriant" and seconda pratica styles.[67] Luzzaschi's book of madrigals for one, two, and three sopranos with keyboard accompaniment, published in 1601 as the well-known Madrigali per cantare e sonare, comprises works written throughout the 1580s.[69][70][e] Newcomb considers this publication the exemplar of the ladies' signature musical style.[70]

Musically, Luzzaschi's works are highly sectionalized and based on melodic themes, rather than harmonic structures. Luzzaschi lessens the sectionalizing effect of his compositional techniques by weakening cadences. His music includes progressive and conservative elements: although his use of vocal imitation creates dense polyphonic textures, akin to earlier 16th-century compositions, his individualistic use of jarring melodic leaps and harmonic dissonance are at odds with older conventions.[71] This freer use of dissonances were closely connected with the style of the concerto delle donne.[72][f]

Other composers who wrote for the concerto include Lodovico Agostini, whose third book of madrigals is among the first publication fully dedicated to the new singing style. He dedicated songs to Guarini, Peverara, and Luzzaschi.[73] Carlo Gesualdo also wrote music for the group while visiting Ferrara in 1594 to marry the Duke's niece Leonora d'Este;[74] much of Gesualdo's music for the group does not survive.[75] Other publications include De Wert's Seventh Book of Madrigals à 5 and Marenzio's First Book à 6,[34] while Monteverdi's Canzonette a tre voci was probably influenced by the group.[65] Some madrigals in the two-book Madrigaletti et napolitane by Giovanni de Macque were written with the Concerto delle donne in mind, due to their technically demanding content.[76]

Works written for the concerto delle donne were not limited to music: The poets Torquato Tasso and Giovanni Battista Guarini wrote works dedicated to the ladies in the concerto, some of which were later set by composers. Tasso wrote over seventy-five poems to Peverara alone.[77]

Influence

[edit]

While they were neither the first nor only female musicians in Ferrara,[1] the concerto delle donne was a revolutionary musical establishment that helped effect a shift in women's role in music; its success took women from obscurity to "the apex of the profession".[78] Women were openly brought to court to train as professional musicians,[79] and by 1600, a woman could have a viable career as a musician, independent of her husband or father.[78] New women's ensembles inspired by the concerto delle donne resulted in more positions for women as professional singers and more music for them to perform.[26] The concerto delle donne contested the viewpoint of some contemporaries that women were unfit to achieve noteworthy deeds.[80]

Despite Alfonso not publicizing the composed music[81] and the dissolution of the court in 1597, the musical style which was inspired by the concerto delle donne spread throughout Europe, and remained prominent for almost fifty years.[39][57] The concerto delle donne was so influential that other courts developed similar concerti and it became a cliché of northern Italian courts,[82][83][84] having one was a sign of prestige.[85] It heavily influenced the development of the madrigal and eventually the seconda practica.[86] The group brought Alfonso and his court international prestige, as the ladies' reputation spread throughout Italy and southern Germany; in 1619 the German composer Michael Praetorius described it as "the latest new Italian style for achieving a good manner of singing".[87] It functioned as a powerful tool of propaganda, projecting an image of strength and affluence.[82][88]

Having seen the concerto delle donne in Ferrara, Caccini created a rival group made up of his family and a pupil. This ensemble was sponsored by the Medici, and traveled as far abroad as Paris to perform for Marie de' Medici.[89] Francesca Caccini had much success composing and singing in the style of the concerto delle donne.[89] Rival groups were planned in Florence by the Medici, Rome by the Orsini, and Mantua by the Gonzaga.[90] There was even a rival group in Ferrara based in the Castello Estense, the very palace where the concerto delle donne performed. This group was formed by Alfonso's sister Lucrezia d'Este, Duchess of Urbino. She had lived at the Este court since 1576, and shortly after Margherita's marriage to Alfonso in 1579, Alfonso and his henchmen killed Lucrezia's lover. Lucrezia was unhappy about being replaced as the matron of the house by Margherita, and upset by the murder of her lover, leading to her desire to be separate from the rest of her family during her evening entertainments.[91][92]

Barbara Strozzi was among the last composers and performers in this style, which by the mid-seventeenth century was considered archaic.[32] At least one instrument used by the concerto delle donne, the harp L'Arpa di Laura in the Galleria Estense art gallery, has become famous.[93]

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b Also known as the concerto di donne or concerto delle (or di ) dame.[1]

- ^ The concerto delle donne may refer to any of the professional female singing ensembles throughout Italy during the late Renaissance; however, it most often refers to the ensemble in Ferrara, which was the earliest and most prominent one.[2] Musicologist Laurie Stras describes them as group "the group most widely recognized as the concerto delle dame"[3]

- ^ The musicologist Judith Tick believes the singer Tarquinia Molza sang with the group, but Anthony Newcomb says she was involved solely as an advisor and instructor.[25][26] The musicologist Karin Pendle only says that Molza "joined the ensemble".[10]

- ^ Outside of the ensemble, Alfonso employed at least two castrati, probably the Spanish brothers Domenico and Hernando Bustamente. Regardless, musicologist Nina Treadwell notes that the Ferrarese "recruitment of castrati waned towards the end of the century with the increased interest in female sopranos".[52]

- ^ This music may have been delayed from publication in order to maintain the secrecy of Alfonso's musica secreta, and to maintain control over it. Newcomb considers this publication the exemplar of the ladies' signature musical style.[69][70]

- ^ In Giovanni Artusi's socratic dialogue, the character defending Monteverdi connects haphazard treatment of dissonance with ornamental singing.[72]

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c Stras 2018, p. 2.

- ^ a b LaMay 2005, p. 367.

- ^ Stras 2018, p. 218.

- ^ Schulenberg 2000, pp. 99, 103–104.

- ^ Stolba 1994, p. 190.

- ^ a b Burkholder, Grout & Palisca 2014, p. 208.

- ^ Taruskin 2010, § "Vernacular Song Genres: Italy".

- ^ Burkholder, Grout & Palisca 2014, p. 210.

- ^ Fenlon 1980, p. 125.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Pendle 2001, p. 80.

- ^ a b Morton 2022, p. 156.

- ^ Newcomb 1980, p. 4.

- ^ a b c d Burkholder, Grout & Palisca 2014, p. 216.

- ^ a b Stark 1999, p. 190.

- ^ a b c Newcomb 1986, p. 96.

- ^ a b Ugolini 2020, p. 71.

- ^ Newcomb 1980, pp. 7, 106, 120.

- ^ Stras 2018, pp. 229–230.

- ^ Newcomb 1980, pp. 20–21.

- ^ a b Newcomb 1980, p. 20.

- ^ Stras 2018, p. 140.

- ^ Newcomb 1980, p. 56.

- ^ Arnold 1982, pp. 253–254.

- ^ Treadwell 2002, p. 28.

- ^ a b Newcomb 2001.

- ^ a b c Tick 2001.

- ^ Pendle 2001, p. 40.

- ^ Newcomb 1980, p. 7.

- ^ Newcomb 1980, p. 11.

- ^ LaMay 2002, p. 49.

- ^ Knighton & Fallows 1998, p. 95.

- ^ a b c Springfels.

- ^ Newcomb 1980, p. 19.

- ^ a b Newcomb 1980, p. 23.

- ^ HaCohen 2001, p. 630.

- ^ Fenlon 2001a.

- ^ Hammond 2004, p. 156.

- ^ Haskell 1980, p. 25.

- ^ a b Newcomb 1980, p. 153.

- ^ Stras 2018, p. 4.

- ^ Newcomb 1986, p. 97.

- ^ Savan 2018, p. 574.

- ^ Jensen et al. 2021, p. 49.

- ^ McClary 2012, p. 82.

- ^ Pendle 2001, p. 82.

- ^ Newcomb 1980, p. 35.

- ^ Treadwell 2002, p. 29.

- ^ Newcomb 1980, p. 183.

- ^ Newcomb 1980, p. 170.

- ^ Clapton 2006.

- ^ Whenham 2001.

- ^ Treadwell 2000, p. 43.

- ^ Sherr 1980.

- ^ a b Newcomb 1980, p. 25.

- ^ a b Newcomb 1980, p. 26.

- ^ Newcomb 1980, p. 59.

- ^ a b McClary 2012, p. 83.

- ^ Newcomb 1980, p. 57.

- ^ Newcomb 1980, p. 58.

- ^ Stark 1999, p. 193.

- ^ Stras 2018, p. 241.

- ^ Newcomb 1986, p. 106.

- ^ Newcomb 1980, pp. 28, 69, 84.

- ^ a b Newcomb 1980, p. 85.

- ^ a b Carter & Chew 2001.

- ^ Newcomb 1980, p. 116.

- ^ a b Newcomb 1980, pp. 115–116.

- ^ Treadwell 2000, p. 78.

- ^ a b Stark 1999, p. 155.

- ^ a b c Newcomb 1980, p. 53.

- ^ Newcomb 1980, pp. 120–125.

- ^ a b Newcomb 1980, p. 83.

- ^ Fenlon 2001b.

- ^ Bianconi 2001.

- ^ Watkins 1991, p. 300.

- ^ Shindle 2001.

- ^ Newcomb 1980, p. 189.

- ^ a b Newcomb 1986, p. 93.

- ^ Newcomb 1986, p. 98.

- ^ Ugolini 2020, p. 72.

- ^ Morton 2022, p. 157.

- ^ a b Newcomb 1986, pp. 97, 98, 99.

- ^ Tomlinson 2017, p. 4.

- ^ Cusick 1993, p. 17.

- ^ Treadwell 2004, p. 2.

- ^ Pendle 2001, p. 83; Cusick 1993, p. 17; Morton 2022, p. 156, reiterated by Newcomb 1980.

- ^ Wistreich 2017.

- ^ Stras 2018, p. 1.

- ^ a b Carter & Hitchcock 2001.

- ^ Coluzzi 2019, p. 335.

- ^ Newcomb 1980, p. 101.

- ^ Niwa 2005, p. 34.

- ^ Kuhn 2020, p. 94.

Sources

[edit]- Books

- Burkholder, J. Peter; Grout, Donald Jay; Palisca, Claude V. (2014). A History of Western Music (9th ed.). New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-91829-8.

- Clapton, Nicholas (2006). "Machines Made for Singing". Handel & the Castrati: The Story Behind the 18th-Century Superstar Singers; 29 March – 1 October 2006. London: Handel House Museum. OCLC 254055896.

- Fenlon, Iain (1980). Music and Patronage in Sixteenth-Century Mantua. Vol. 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-59475-000-7.

- Haskell, Francis (1980). Patrons and Painters: A study in the relations between Italian Art and Society in the Age of the Baroque. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-02540-8.

- Jensen, C. R.; Maier, I.; Shamin, S.; Waugh, D. C. (2021). Russia's Theatrical Past: Court Entertainment in the Seventeenth Century. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-05635-1.

- Knighton, Tess; Fallows, David (1998). Companion to Medieval and Renaissance music. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-21081-3.

- LaMay, Thomasin (2002). "Madalena Casulana: My Body Knows Unheard of Songs". In Borgerding, Todd (ed.). Gender, Sexuality, and Early Music. Abingdon-on-Thames: Routledge. pp. 41–72. ISBN 978-0-8153-3394-4.

- LaMay, Thomasin (2005). "Composing from the Throat: Madalena Casulana's Primo libro de madrigali, 1568". In LaMay, Thomasin (ed.). Musical Voices of Early Modern Women: Many-Headed Melodies. Burlington: Ashgate Publishing. pp. 365–397. ISBN 978-0-7546-3742-4.

- McClary, Susan (2012). Desire and Pleasure in Seventeenth-Century Music. Berkley: University of California Press.

- Newcomb, Anthony (1980). The Madrigal at Ferrara, 1579–1597. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-09125-9.

- Newcomb, Anthony (1986). "Courtesans, Muses, or Musicians: Professional Women Musicians in Sixteenth-Century Italy". In Bowers, Jane M.; Tick, Judith (eds.). Women Making Music: the Western Musical Tradition, 1150–1950. Champaign: University of Illinois Press. pp. 90–115. ISBN 978-0-252-01470-3.

- Pendle, Karin (2001). Women and Music: A History. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-21422-5.

- Stark, James (1999). Bel Canto: A History of Vocal Pedagogy. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-8614-3.

- Stras, Laurie (2018). Women and Music in Sixteenth-Century Ferrara. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-316-65045-5.

- Stolba, K Marie (1994). The Development of Western Music: A History (3rd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Companies. ISBN 0-697-29379-3.

- Taruskin, Richard (2010). "Chapter 17: Commercial and Literary Music". Music from the Earliest Notations to the Sixteenth Century. The Oxford History of Western Music. Vol. 1. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-538481-9.

- Treadwell, Nina (2000). Restaging the Siren: Musical Women in the Performance of Sixteenth-Century Italian Theater (PhD). University of Southern California. doi:10.25549/usctheses-c16-138553. OCLC 53291961.

- Treadwell, Nina (2002). "2 "Simil combattimento fatto da Dame": The Musico-theatrical Entertainments of Margherita Gonzaga's balletto delle donne and the Female Warrior in Ferrarese Cultural History". Gender, Sexuality, and Early Music. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-203-05549-6.

- Ugolini, Paola (2020). The Court and its Critics: Anti-court Sentiments in Early Modern Italy. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-1-4875-3216-1.

- Watkins, Glenn (1991). Gesualdo: The Man and His Music. Preface by Igor Stravinsky (2nd ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-816216-2.

- Articles

- Arnold, Denis (1982). "Review of Le settimo libro de' madrigali (1595)". Early Music. 10 (2): 253–255. ISSN 0306-1078.

- Coluzzi, Seth (23 September 2019). "Licks, Polemics, and the Viola Bastarda: Unity and Defiance in Monteverdi's Fifth Book". Early Music. 47 (3): 333–344. doi:10.1093/em/caz040.

- Cusick, Suzanne G. (1 April 1993). "Gendering Modern Music: Thoughts on the Monteverdi-Artusi Controversy". Journal of the American Musicological Society. 46 (1): 1–25. doi:10.2307/831804.

- HaCohen, Ruth (1 September 2001). "The Music of Sympathy in the Arts of the Baroque; or, the Use of Difference to Overcome Indifference". Poetics Today. 22 (3): 607–650. doi:10.1215/03335372-22-3-607.

- Hammond, Frederick (2004). "There is Nothing Like the dame". Early Music. 32 (1): 156–157 – via Project MUSE.

- Kuhn, Eva (2020). Agency of Musical Instruments: The Resonance of Instruments without Sounds in the Collection of Francesco II d’Este. 19th Biennial International Conference on Baroque Music. Birmingham. p. 94.

- Morton, Joëlle (22 December 2022). "Will Wonders Never Cease? The Viola Bastarda at the Ferrarese Court". Early Music. 50 (2): 155–168. doi:10.1093/em/caac036.

- Niwa, S. (1 February 2005). "'Madama' Margaret of Parma's patronage of music". Early Music. 33 (1): 25–38. doi:10.1093/em/cah039.

- Savan, Jamie (31 December 2018). "Revoicing a 'Choice Eunuch': The Cornett and Historical Models of Vocality". Early Music. 46 (4): 561–578. doi:10.1093/em/cay068.

- Schulenberg, David (2000). "History of European Art Music". In Rice, Timothy; Porter, James; Goertzen, Chris (eds.). The Garland Encyclopedia of World Music: Europe. Abingdon-on-Thames: Routledge. pp. 99–119. ISBN 0-8240-6034-2.

- Sherr, Richard (Spring 1980). "Gugliemo Gonzaga and the Castrati". Renaissance Quarterly. 33 (1). Renaissance Society of America: 33–56. doi:10.2307/2861534. ISSN 0034-4338. JSTOR 2861534.

- Springfels, Mary. "Newberry Consort Repertoire - Daughters of the Muse". Chicago: Newberry Library. Archived from the original on 13 May 2006. Retrieved 11 July 2006.

- Tomlinson, Gary (9 August 2017). "Consider the Madrigal". Per Musi (36). ISSN 2317-6377.

- Treadwell, Nina (March 2004). "She descended on a cloud 'from the highest spheres': Florentine monody 'alla Romanina'". Cambridge Opera Journal. 16 (1): 1–22. doi:10.1017/S0954586704001764. ISSN 1474-0621.

- Wistreich, Richard (5 July 2017). "'Inclosed in This Tabernacle of Flesh': Body, Soul, and the Singing Voice". Journal of the Northern Renaissance (8).

- Grove sources

- Bianconi, Lorenzo (2001). "Gesualdo, Carlo, Prince of Venosa, Count of Conza". Grove Music Online. Revised by Glenn Watkins. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.10994. ISBN 978-1-56159-263-0. Retrieved 11 April 2006. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Carter, Tim; Hitchcock, H. Wiley (2001). "(1) Giulio Romolo Caccini [Giulio Romano]". Grove Music Online. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.40146. ISBN 978-1-56159-263-0. Retrieved 11 April 2006. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Carter, Tim; Chew, Geoffrey (2001). "Monteverdi [Monteverde], Claudio". Grove Music Online. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.44352. ISBN 978-1-56159-263-0. Retrieved 11 April 2006. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Fenlon, Iain (2001a). "Fiorini [Fiorino], Ippolito". Grove Music Online. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.09702. ISBN 978-1-56159-263-0. Retrieved 11 April 2006. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Fenlon, Iain (2001b). "Agostini, Lodovico". Grove Music Online. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.00301. ISBN 978-1-56159-263-0. Retrieved 11 April 2006. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Newcomb, Anthony (2001). "Molza, Tarquinia". Grove Music Online. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.18918. ISBN 978-1-56159-263-0. Retrieved 11 April 2006. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Shindle, W. Richard (2001). "Macque, Giovanni de". Grove Music Online. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.17378. ISBN 978-1-56159-263-0. Retrieved 11 April 2006. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Tick, Judith (2001). "Women in music, §II: Western classical traditions in Europe & the USA 3. 1500–1800". Grove Music Online. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.52554. ISBN 978-1-56159-263-0. Retrieved 11 April 2006. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Whenham, John (2001). "Orfeo(i)". Grove Music Online. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.O005849. ISBN 978-1-56159-263-0. Retrieved 11 April 2006. (subscription or UK public library membership required)