Gio Ponti

This article needs additional or more specific images. (November 2024) |

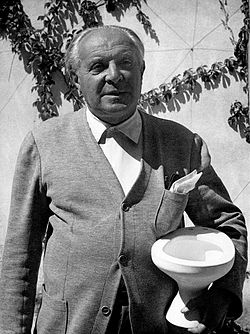

Gio Ponti | |

|---|---|

Ponti in the 1950s | |

| Born | 18 November 1891 Milan, Italy |

| Died | 16 September 1979 (aged 87) Milan, Italy |

| Alma mater | Polytechnic University of Milan |

| Occupation | Architect |

| Buildings |

|

Giovanni "Gio" Ponti (Italian pronunciation: [ˌdʒo pˈponti]; 18 November 1891 – 16 September 1979) was an Italian architect, industrial designer, furniture designer, artist, teacher, writer and publisher.[4]

During his career, which spanned six decades, Ponti built more than a hundred buildings in Italy and in the rest of the world. He designed a considerable number of decorative art and design objects as well as furniture.[5] Thanks to the magazine Domus, which he founded in 1928 and directed almost all his life, and thanks to his active participation in exhibitions such as the Milan Triennial, he was also an enthusiastic advocate of an Italian-style art of living and a major player in the renewal of Italian design after the Second World War.[6] From 1936 to 1961, he taught at the Milan Polytechnic School and trained several generations of designers. Ponti also contributed to the creation in 1954 of one of the most important design awards: the Compasso d'Oro, and was himself awarded the prize in 1956.[7][8] Ponti died on 16 September 1979.

His most famous works are the Pirelli Tower, built from 1956 to 1960 in Milan in collaboration with the engineer Pier Luigi Nervi, the Villa Planchart in Caracas and the Superleggera chair,[9] produced by Cassina in 1957.

Early life and education

[edit]Ponti was born in Milan in 1891[10] to Enrico Ponti and Giovanna (Rigone). His studies were interrupted by his military service during World War I. He served as a Capitan in the Pontonier Corps (Corps of Engineers) from 1916 to 1918 and was awarded both the Bronze Medal of Military Valor and the Italian Military Cross.[citation needed]

Ponti graduated with a degree in architecture from the Politecnico di Milano University in 1921.[11] The same year, he married Giulia Vimercati, with whom he had four children, Lisa, Giovanna, Letizia, and Giulio, and eight grandchildren.[citation needed]

Architecture and interior design

[edit]

Ponti began his architectural career in partnership with Mino Fiocchi and Emilio Lancia from 1923 through 1927, and then through 1933 with Lancia only, as Studio Ponti e Lancia PL. In these years he was influenced by and associated with the Milanese neoclassical Novecento Italiano movement. In 1925, Ponti participated in the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts in Paris, with the porcelain manufacturer. On this occasion, he made friends with Tony Bouilhet, director of the silversmith company Christofle. The family Bouilhet who entrusted him with his first architectural commission abroad, with the construction of the Ange Volant (1926–1928, in collaboration with Emilio Lancia and Tomaso Buzzi), a country house located on the edge of the Saint-Cloud golf course, on the outskirts of Paris. As he built his first building in Milan, via Randaccio (1925–1926), the Ange Volant was an opportunity for Ponti to experiment with his personal conception of the Italian-style house, the principles of which he gathered in his book La Casa all'Italiana published in 1933. Other outputs of the time include the 1928 Monument to the Fallen with the Novecento architects Giovanni Muzio, Tomaso Buzzi, Ottavio Cabiati, Emilio Lancia and Alberto Alpago Novello.

The 1930s were years of intense activity for Ponti. He was involved in many projects, particularly in his native city of Milan. With the construction of the Borletti funeral chapel in 1931, he started to adopt a modernist shift. By removing all ornament, Ponti moved towards formal simplification where he sought to make style and structure coincide. The ten "case tipiche" (typical houses), built in Milan between 1931 and 1938, were also close to Rationalist Modernism while retaining features of Mediterranean houses like balconies, terraces, loggias and pergolas. Spacious, equipped and built with modern materials, they met the requirements of the new Milanese bourgeoisie. The construction of the Rasini building (1933–1936) with its flat roofs marked the end of his partnership with Emilio Lancia around 1933. He then joined forces with engineers Antonio Fornaroli and Eugenio Soncini to form Studio Ponti-Fornaroli-Soncini which lasted until 1945.[12]

For the 1933 Fifth Triennial of Decorative Arts in Milan, Giovanni Muzio designed the Palazzo dell'Arte in Parco Sempione, a museum and theater to host the displays. Adjacent to the palace, a steel tower-spire was commissioned from Gio Ponti. The 108-meter-high (354 ft) Littoria Tower (or Lictor's Tower, but now Branca Tower), was meant to resemble the bundles that formed the fasces. It was topped by a panoramic restaurant. Putatively the tower height was limited by Mussolini so as not to exceed the height of the Madonnina statue atop the Duomo.[13][14]

With the first office building of the Montecatini chemical group (1935–1938), for which he used the latest techniques and materials produced by the firm, in order to reflect the company's avant-garde spirit, Ponti designed, on an unprecedented scale (the offices housed 1,500 workstations), a building in every detail, from architecture to furniture.[15]

Ponti is also involved in the project to expand the new university campus in Rome, led by the urban planner Marcello Piacentini by designing the School of Mathematics school, inaugurated in 1935.[16] Ponti chose bright and functional spaces with simple lines, including a fan-shaped building that housed three amphitheaters. From 1934 to 1942, he worked at the University of Padua, with the construction and interior design of the new Faculty of Arts, Il Liviano (1934–1940), then the artistic direction and interior design of the Aula Magna, the basilica and the rectorate of the Palazzo Bo.[17] In the late 1930s, Ponti deepened his research on Mediterranean housing by collaborating with writer and architect Bernard Rudofsky. Together, they imagined in 1938 the Albergo nel bosco on the island of Capri, a hotel designed as a village of house-bedrooms, all unique and scattered in the landscape.

At the turn of the 1940s, architectural projects continued initially for Ponti, with the construction of the Columbus Clinic (1939–1949) in Milan, and the interior design of the Palazzo del Bo at the University of Padua where he carried out a monumental fresco on the stairs leading to the rectorate.[17] From 1943, due to the Second World War, his activity as an architect slowed down. This period corresponded to a period of reflection in which Ponti devoted himself to writing and designing sets and costumes for theatre and opera, such as Igor Stravinsky's Pulcinella for the Triennial Theatre in 1940, or Christoph Willibald Gluck's Orfeo ed Euridice for the Milan Scala in 1947. He also planned a film adaptation of Luigi Pirandello's Enrico IV for Louis Jouvet and Anton Giulio Bragaglia.

After World War 2, with the emergence of the Italian economic boom, the 1950s were a busy time for Ponti, who traveled abroad. He participated in the redevelopment and interior design of several Italian liners (Conte Grande et Conte Biancamano, 1949, Andrea Doria and Giulio Cesare, 1950, Oceania, 1951), showcases the know-how of his country.[18] Construction continued in Milan. In 1952, he created a new agency with Antonio Fornaroli and his son-in-law Alberto Rosselli. This vast hangar was designed as an architecture laboratory, an exhibition space and a space for the presentation of studies and models. After the death of Rosselli, he continued to work with his longtime partner Fornaroli. A block away, in via Dezza, Ponti built a nine-story apartment building, which housed his family. From 1950 to 1955, he was also in charge of the urban planning project for the Harar-Dessiè social housing district in Milan with architects Luigi Figini and Gino Pollini. For this complex, he designed two buildings with highly colored profiles, one of which was designed in collaboration with the architect Gigi Gho.[4]

With the help of engineer Pier Luigi Nervi, a concrete specialist who advised him on the structure, he built with his studio and Arturo Danusso the Pirelli tower (1956–1960).[19] Facing Milan's main station, this 31-story, 127-meter-high (417 ft) skyscraper housed the headquarters of Pirelli, a company specializing in tyres and rubber products. At the time of its inauguration, and for a few months, it was the tallest building in Europe. Together with the Galfa Tower by Melchiorre Bega (1956–1959) and the Velasca Tower (1955–1961) of the BBPR Group, this skyscraper changed Milan's landscape. From 1953 to 1957, he built the Hotel della Città et de la Ville and the Centro Studi Fondazione Livio e Maria Garzanti, in Forlì (Italy), by the assignment of Aldo Garzanti, a famous Italian publisher.

In the 1950s, and thanks to his role in the Domus Magazine, Ponti was internationally known and commissions were multiplying, with constructions in Venezuela, Sweden, Iraq and projects in Brazil.[12] In New York City, he set up the Alitalia airline agency (1958) on Fifth Avenue and was entrusted with the construction of the 250-seat auditorium of the Time-Life building (1959).[4] In Caracas, Ponti had freedom to accomplish one of his masterpieces: the Villa Planchart (1953–1957), a house designed as a work of art on the heights of the capital, immersed in a tropical garden. Conceived as large-scale abstract sculpture, it can be seen from the inside as an uninterrupted sequence of points of view where light and color prevail. Outside, the walls were like suspended screens that defined the space of the house. At night, a lighting system highlighted its contours. All the materials and the furniture, chosen or designed by Ponti, were shipped from Italy.[20] The overall effect has been noted for its "lightness": "the Villa Planchard sits so lightly on the hillside above Caracas that it is known as the 'butterfly house.'"[21] A few miles away, Ponti designed for Blanca Arreaza, the Diamantina (1954–1956), so-called because of the diamond-shaped tiles that partially cover its facade. This villa has since been destroyed.

In the field of interior design, Ponti multiplied inventions and favoured multifunctional solutions; In 1951, he developed an ideal hotel room for the Milan Triennial, in which he presented a "dashboard" bed headboard composed of shelves, some of which were mobile, and control buttons for electricity or radio. He then applied this solution to domestic spaces and offices, with "organised walls". Next came the "fitted windows", for the manufacturer Altamira in particular and that he used for his apartment via Dezza.[4] With its vertical and horizontal frames through which shelves, bookcases and frames can be arranged, the "fitted window" became the fourth transparent wall of a room and ensured a transition between the inside and the outside.

The 1960s and 1970s were dominated by international architectural projects in places like Tehran, Islamabad and Hong Kong, where Ponti developed new architectural solutions: the façades of his buildings became lighter and seemed to be detached like suspended screens. With the church of San Francesco al Fopponino in Milan (1961–1964), he created his first façade with perforated hexagonal openings. The sky and light became important protagonists of his architecture. This theatricality was reinforced by the omnipresence of ceramics, whose uses he reinvented both indoors and outdoors. In collaboration with the Milanese firm Ceramica Joo, he created diamond-shaped tiles with which he covered most of his facades (Villa Arreaza in Caracas, 1954–1956, Villa Nemazee in Tehran, 1957–1964, Shui Hing department store in Hong Kong, 1963, San Carlo Borromeo Hospital Church, 1964–1967 and Montedoria building, 1964–1970 in Milan). With Ceramica D'Agostino, he designed tiles with blue and white or green and white motifs that once combined create different more than a hundred motifs. They were used for the interior decoration of the hotels Parco dei Principi in Sorrento (1960) and in Rome (1961–1964). The Hotel Parco dei Principi in Sorrento was one of the first design hotel in Italy. Ponti also offered to Domus readers detailed plans of a circular house called Il scarabeo sotto la foglia (1964– The beetle under a leaf). This small oval building was covered with white and green ceramic tiles, both inside and outside, including the roof. Its envelope reflected the surrounding landscape and blended into it, like the shell of a beetle. In 1966, collector Giobatta Meneguzzo built his version of the beetle under a leaf in the province of Vicenza and entrusted the Italian designer Nanda Vigo for the interior design. With the Bijenkorf department store in Eindhoven in the Netherlands (1966–1969), Ponti proposed another solution, by creating a tiled façade for an existing building. Modular, it was enlivened thanks to the non-uniform arrangement of its openings with various shapes. Lit from behind, the facade turned into a bright screen at night. Facing the building, Ponti designed a living square where the inhabitants could meet and rest on sculptures built for this purpose. Ponti also deepened his reflection on the skyscraper with a project of triangular and coloured towers (1967–1969).

In the last years of his life, Ponti was more than ever in search of transparency and lightness. He saw his facades as folded and perforated sheets of paper with geometric shapes. The 1970s began with the inauguration in 1970 of the Taranto Cathedral, a white rectangular building topped with a huge concrete facade perforated with openings, such that it is referred to locally as "the sail."[21] In 1971, he participated in the construction of the Denver Art Museum in Colorado, taking care of the building's exterior envelope. He also submitted in 1971 a project for the future Centre Georges-Pompidou in Paris by proposing to model an axis in the capital linking the Baltard pavilions in les Halles pavilions to the future modern art museum thanks to an art "garden".

- Architecture designed by Ponti photographed by Paolo Monti (Fondo Paolo Monti, BEIC)

-

Harar quarter, Milan (1950)

-

RAS building, Milan (1956–1960)

Decorative arts and industrial design

[edit]In 1923, Ponti was appointed artistic director of Richard Ginori, one of Italy's leading porcelain manufacturers, based in Milan and Sesto Fiorentino, changing the company's whole output through the involvement of some of the main Italian artists of the time, including the sculptor Salvatore Saponaro.[22][23] He completely renewed the iconographic repertoire by freely revisiting the classical tradition. He also rationalized the production system of the pieces while maintaining their high quality of execution. The pieces were presented at the first decorative arts biennial in Monza in 1923. With his new designs, he won the great prize for ceramics in 1925 at the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts in Paris.[24] After this major success, Ponti played a major role in the modernisation of Italian decorative arts, especially thanks to his involvement in the Monza Biennials and the Milan Triennials. In the 1920s, Ponti began numerous collaborations, notably with the silverware company Christofle, the glassmakers Venini and Fontana Arte. He also founded the Labirinto group, with Tomaso Buzzi, Pietro Chiesa and Paolo Venini, among others. The Labirinto unique piece furniture was made of luxurious materials; at the same time, he designed Domus Nova with Emilio Lancia, a furniture collection with simple lines that was produced in series and sold by the Milanese department store La Rinascente.[25]

In the 1930s, while Ponti continued to design unique pieces of furniture for specific interiors, and encouraged the promotion of quality series production. In 1930, he designed furniture and lighting for the glassmaker Fontana and became in 1933, together with Pietro Chiesa, the artistic director of the branch Fontana Arte. He created in particular a cylindrical lamp surrounded by crystal discs and mirrors and the famous Bilia Lamp.[26]

In the 1940s and early 1950s, Ponti turned to unique creations showcasing the skills of exceptional craftsmen. With the artist and enameller Paolo De Poli, they created enamelled panels and brightly colored furniture. In 1956, they imagined an imaginary and colorful bestiary, light decorative objects such as cut and folded paper. Other collaborations were established, in particular with the Dal Monte brothers, who specialised in the production of papier-mâché objects, the ceramist Pietro Melandri, the porcelain manufacturer Richard Ginori and the Venini glass factory in Murano. From 1946 to 1950, he designed many objects for this glassmaker: bottles, chandeliers, including a multicoloured chandelier. The bottles evoke stylized female bodies.[27] It was also in 1940 that he began working with the decorator and designer Piero Fornasetti. This fruitful collaboration, during which they designed furniture and many interiors where ornament and fantasy prevailed (Palazzo del Bo in Padua – 1940, Dulcioria pastry shop in Milan–1949, Sanremo casino – 1950, the liners Conte Grande – 1949 and Andrea Doria – 1950, etc.), spanned two decades.[28]

At the turn of the 1950s, Ponti deployed a prolific creation where he sought to combine aesthetic and functional requirements: the espresso machine for La Pavoni in 1948 and the Visetta sewing machine for Visa (1949), textiles for JSA, door handles for Olivari, a range of sanitary facilities for Ideal Standard, cutlery for Krupp Italiana and Christofle, lighting for Arredoluce and furniture for the Swedish department store Nordiska Kompaniet.[27] From its fruitful collaboration with Cassina, the Leggera and Superleggera (superlight) chairs, the Distex, Round, Lotus and Mariposa chairs are now among the classics of Italian design.[29] In 1957, the Superleggera chair designed for Cassina, and still produced today, was put on the market. Starting from the traditional chair model, originating from the village of Chiavari in Liguria, Ponti eliminated all unnecessary weight and material and assimilated the shape as much as possible to the structure, in order to obtain a modern silhouette weighing only 1.7 kg. the chair, which was very strong but also so light that it can be lifted by a child using just one finger.[29] Some of his furniture is now being reissued by Molteni&C. In the United States, he participated in the exhibition Italy at Work at the Brooklyn Museum in 1950, and created furniture for Singer & Sons, Altamira, and cutlery for Reed & Barton ("Diamond" flatware, 1958),[27] adapted for production by designer Robert H. Ramp).

Many models also emerged in the 1960s, such as the Continuum rattan armchair for Pierantonio Bonacina (1963), wooden armchairs for Knoll International (1964), the Dezza armchair for Poltrona Frau (1966), a sofa bed for Arflex, the Novedra armchair for C&B (1968) or the Triposto stool for Tecno (1968). He invented lighting fixtures for Fontana Arte, Artemide (1967), Lumi (1960), and Guzzini (1967), but also fabrics for JSA and a dinner service for Ceramica Franco Pozzi (1967).

In 1970, Ponti presented his concept of an adapted house (casa adatta) at Eurodomus 3 in Milan, where the house is centred around a spacious room with sliding partitions, around which the rooms and service areas gravitate. The space requirement for furniture and services was reduced to a minimum. The furniture also became flexible and space-saving in order to optimise space. The Gabriela chair (1971) with a reduced seat, as well as the Apta furniture series (1970) for Walter Ponti, illustrated this new way of life.

Ponti continued to create wall and floor coverings whose graphic rendering becomes a work of art in itself. Foliage patterns were developed on tiles for Ceramica D'Agostino. Together with this manufacturer, he also produced geometrically decorated and coloured tiles to cover the floors of the Salzburger Nachrichten newspaper's headquarters in Salzburg in 1976. A similar process was used in 1978 to cover the facade of the Shui Hing department store in Singapore. Finally, that same year, his ultimate decorative and poetic shapes, a bestiary of folded silver leaves, were interpreted by the silversmith Lino Sabattini. Ponti died on 16 September 1979.

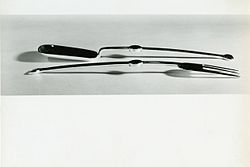

- Design by Ponti photographed by Paolo Monti

-

Dessert spoon and fork (Sabattini); photo 1963.

-

Cutlery, 1955–1958 ca.

-

Cutlery, 1955–1960 ca.

-

Ceramic sanitaries for Ideal Standard, 1954 ca.

Creative advocacy and activity

[edit]From the beginning of his career, Ponti promoted Italian creation in all its aspects. In a 1940 publication, he wrote that: "The Italians were born to build. Building is a characteristic of their race, it informs their mentality, commitment to their work and destiny, it is the expression of their existence, and the supreme and immortal mark of their history."[30]

From a simple participant, he became a member of the steering committee of the Monza Biennials in 1927, where he advocated for a closer bond between crafts and industry. Thanks to his involvement, the Biennale underwent tremendous development: renamed the Triennial of Art and Modern Architecture in 1930 and relocated to Milan in 1933, it became a privileged place to observe innovation at the international level.

Within the new multidisciplinary review of art, architecture and interior design Domus, which he founded in 1928 with the publisher Gianni Mazzochi and which he directed almost all his life, Ponti had the opportunity to spread his ideas.[31] The aim of this review was to document all forms of artistic expression in order to stimulate creation through an independent critical perspective. A mirror of the architectural and decorative arts trends, it introduced Italian readers to the modernist movement and creators such as Le Corbusier, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Jean-Michel Frank and Marcel Breuer. Ponti also presented the work of Charles Eames and of the decorator Piero Fornasetti. Over the years, the magazine became more international and played an important role in the evolution of Italian and international design and architecture. Still published today, Domus is a reference in the fields of architecture and design.

In 1941 Ponti resigned as editor of Domus and set up Stile magazine—an architecture and design magazine sympathetic to the fascist regime—which he edited until 1947.[32] In the magazine, which expressed clear support for fascist Italy and Nazi Germany, in reference to the regime, Ponti wrote: "our great allies give us an example of tenacious, very serious, organized and orderly application "(Stile, August 1941).[citation needed] Stile only lasted a few years and shut-down after the Aglo-American liberation of Italy and the defeat of The Rome-Berlin Axis.

In 1948 he returned to Domus, where he remained as editor until his death. His daughter Lisa Licitra Ponti soon joined the editorial team. In the 1950s, the review became more international and the reopening of borders encouraged confrontation with different cultural and visual worlds. Thanks to his involvement in numerous exhibitions, Ponti established himself as a major player in the development of post-war design and the diffusion of "Made in Italy".[citation needed]

In 1957, Ponti published Amate l'architettura (In Praise of Architecture), his seminal work where he defined the expression of a finished form (la forma finita) that was simple, light, and did not allow any possibility of extension, addition, repetition or superposition. This concept applied to architecture as well as art and design. It was symbolized by the hexagonal shape of the diamond that Ponti used in many of his creations.

In the 1950s and in the 1960s, Ponti multiplied events in Italy and abroad. In 1964, he organised a series of exhibitions in the Ideal Standard showroom in Milan, named "Espressioni", featuring a generation of talents such as Achille and Pier Giacomo Castiglioni, Enzo Mari, Bruno Munari, Ettore Sottsass, Nanda Vigo or the artists Lucio Fontana and Michelangelo Pistoletto. It was also in the mid-1960s that he befriended art critic Pierre Restany, who became a regular contributor to the Domus magazine. Ponti also coordinated the Italian and European editions of the Eurodomus design exhibitions, including the exhibition "Formes italiennes" in 1967 at the Galeries Lafayette in Paris. At Eurodomus 2 in Turin in 1968, Ponti presented a model of a city, Autilia, for which he imagined a continuous vehicle circulation system. The art historian Nathan Shapira, his student and disciple, organised that same year, with the help of Ponti, his first retrospective exhibition which travelled the United States for two years.

From 1936 to 1961 he worked as a professor on the permanent staff of the Faculty of Architecture at Politecnico di Milano University.

Awards

[edit]In 1934 he was given the title of "Commander" of the Royal Order of Vasa in Stockholm. He also obtained the Accademia d'Italia Art Prize for his artistic merits, as well as a gold medal from the Paris Académie d'Architecture. Finally, he obtained an honorary doctorate from the London Royal College of Art.[33]

Selected works and projects

[edit]Architecture and interior design

[edit]- 1924–1926: via Randaccio building, Milan, Italy

- 1926–1928: country house l'Ange volant, Paris Region, France

- 1928: Borletti building, via San Vittore, Milan, Italy

- 1928–1930: Via Domenichino building, Milan, Italy (interior design and furnishing of the Vimercati apartment in the building)

- 1931: Borletti funerary chapel, Milan, Italy

- 1931–1932: Interior design of the restaurant Ferrario, Milan stock exchange, Palazzo Mezzanotte, piazza degli affari, Milan, Italy

- 1931–1936: Case tipiche (typical houses), via de Togni, Milan, Italy (1931–1934, Domus Julia; 1932–1934, Domus Fausta; 1932–1936, Domus Carola)

- 1932–1935: School of Mathematics, university campus la Sapienza, Rome, Italy

- 1932–1936: ItalCima chocolate factory, via Crespi, Milan, Italy

- 1933: Littoria tower (today the Branca tower), Milan, Italy

- 1933–1936: Rasini building, bastioni di Porta Venezia, Milan, Italy

- 1933–1938: Case tipiche (typical houses), via Letizia and via del Caravaggio, Milan, Italy (1933–1936, Domus Serena; 1933–1937, Domus Livia, Domus Aurelia, Domus Honoria; 1938, Domus Flavia)

- 1934: De Bartolomeis villas, Val Seriana, Italy

- 1934: Room "Più leggero dell'aria" ("Lighter than air") at the Esposizione dell’aeronautica italiana, Palazzo dell'Arte, Milan, Italy

- 1934–1935: Domus Adele (Magnaghi and Bassanini building), viale Zugna, Milan, Italy

- 1934–1940: Faculty of the Arts, Il Liviano, University of Padua, piazza del Capitanato, Padua, Italy

- 1935–1936: Laporte house, via Benedetto Brin, Milan, Italy

- 1935–1936: Interior design and furnishing of the Italian cultural institute, Lützow-Fürstenberg Palace, Vienna, Austria

- 1935–1937: Paradiso del Cevedale hotel, Val Martello, Bolzano, Italy

- 1935–1938: First Montecatini building, via Turati, Milan, Italy

- 1936: Design of the universal exhibition of the catholic press, Vatican, Italy

- 1936–1938: Domus Alba, via Goldoni, Milan, Italy

- 1936–1942: Ferrania building (today Fiat), corso Matteotti, Milan, Italy

- 1936–1942: Artistic direction and interior design of the Aula Magna, basilica and administrative building of Palazzo del Bo, University of Padua, Padua, Italy

- 1938: San Michele hotel, Capri, Italy (project)

- 1938: Design of the "Mostra della Vittoria", Fiera di Padova, Padua, Italy

- 1938–1949: Columbus clinic, via Buonarroti, Milan, Italy

- 1939: Competition for the Palazzo dell'Acqua e della Luce ("Palace of Water and Light") for the E42, Rome, Italy (project)

- 1939–1952: Piazza San Babila building, Milan, Italy

- 1939–1952: RAI headquarters(ex-EIAR), corso Sempione, Milan, Italy

- 1947–1951: Second Montecatini building, largo Donegani, Milan, Italy

- 1949: Interior design of the ocean liners Conte Biancamano and Conte Grande for Società di Navigazione Italia, Genoa, Italy

- 1950: Interior design of the ocean liners Andrea Doria and Giulio Cesare for Società di Navigazione, Gruppo IRI-Finmare, Genoa, Italy

- 1950–1955: Urban planning and buildings for Ina, Harrar-Dessiè neighborhood, Milan, Italy

- 1951: Competition for the interior design of the ocean liners Asia and Vittoria (project)

- 1951: Interior design of the ocean liner Oceania for Lloyd Triestino, Trieste, Italy

- 1952: Architecture studio Ponti-Fornaroli-Rosselli, via Dezza, Milan, Italy

- 1952: Interior design of the ocean liner Africa for Lloyd Triestino, Trieste, Italy

- 1952: Interior design of the Casa di Fantasia, Piazza Piemonte, Milan, Italy

- 1952–1958: Italian cultural institute, Carlo Maurillo Lerici Foundation, Stockholm, Sweden

- 1953: Italian-Brazilian-Centre, Predio d'Italia, São Paulo, Brazil (project)

- 1953: Institute of nuclear physics, São Paulo, Brazil (project)

- 1953: Villa Taglianetti, São Paulo, Brazil (project)

- 1953–1957: Villa Planchart, Caracas, Venezuela

- 1954–1956: Villa Arreaza, Caracas, Venezuela

- 1955–1960: San Luca Evangelista church, via Vallazze, Milan, Italy

Major Achievements and Projects

[edit]- 1956–1957: Building, via Dezza, Milan, Italy

- 1956–1960: Pirelli tower, piazza Duca d'Aosta, Milan, Italy

- 1956–1962: Development board, Baghdad, Iraq

- 1957–1959: Carmelite convent, Bonmoschetto, Sanremo, Italy

- 1957–1964: Villa Nemazee (fa), Tehran, Iran

- 1958: Interior design of the Alitalia agency, Fifth Avenue, New York City, United States

- 1958–1962: RAS office building, via Santa Sofia, Milan, Italy

- 1959: Auditorium of the Time-Life Building, Sixth Avenue, New York City, United States

- 1960: Parco dei Principi hotel, Sorrento, Italy

- 1961: Design of the Mostra internazionale del lavoro, Italia'61, Turin, Italy

- 1961–1963: Facade of the Shui Hing department store, Nathan Road, Hong Kong

- 1961–1964: Parco dei Principi hotel, via Mercadante, Rome, Italy

- 1961–1964: San Francesco al Fopponino church, via Paolo Giovio, Milan, Italy

- 1962: Pakistan House hotel, Islamabad, Pakistan

- 1962–1964: Ministerial buildings, Islamabad, Pakistan

- 1963: Villa for Daniel Koo, Hong Kong

- 1964: Scarabeo sotto una foglia (Beetle under a leaf), villa Anguissola, Lido di Camaiore, Massa Carrara, Italy

- 1964–1967: San Carlo Borromeo hospital church, via San Giusto, Milan, Italy

- 1964–1970: Montedoria building, via Pergolesi, Milan, Italy

- 1964–1970: Cathedral, Taranto, Italy

- 1966: Canopy for the main basilica at the Oropa sanctuary, Biella, Italy

- 1966–1969: Facade of De Bijenkorf department store, Eindhoven, Netherlands

- 1967–1969: Colourful and triangular skyscrapers (project)

- 1970–1972: Denver Art Museum, Denver, Colorado, United States

- 1971: Competition for the Plateau Beaubourg, Paris, France (project)

- 1974: Facade for the Mony Konf building, Hong Kong

- 1976: Tile floors for the headquarters of the Salzburger Nachtrichten newspaper, Salzburg, Austria

- 1977–1978: Facade of the Shui Hing department store, Singapore

Decorative arts and design

[edit]- 1923–1938: Ceramics and porcelain for Richard Ginori, Doccia factory in Sesto Fiorentino, and San Cristoforo factory in Milan, Italy

- 1927: pewter and silver objects for Christofle, Paris, France

- 1927–1930: creation of two furniture collections, Il Labirinto and Domus Nova, Milan, Italy

- 1930: Furniture and objets for Fontana Arte, Milan, Italy Beginning of partnership with Fontana Arte.

- 1930–1933: Textiles for Vittorio Ferrari, Milan, Italy

- 1930–1936: Cutlery for Krupp Italiana, Milan, Italy

- 1940: Paintings and objects made from enamel on copper in collaboration with Paolo De Poli, Padua, Italy

- 1940: Sets and costumes for Pulcinella by Igor Stravinsky, Teatro dell'Arte, Milan, Italy

- 1940–1959: furniture and interior design in partnership with Piero Fornasetti

- 1941–1947: Furniture decorated with enamel in collaboration with Paolo De Poli, Padua, Italy

- 1942–1943: Film adaptation of the play Henry IV by Luigi Pirandello (project)

- 1944: Sets and costumes for the ballet Festa Romantica by Giuseppe Piccioli, la Scala, Milan, Italy

- 1945: Furniture for Saffa, "La casa entro l'armadio" (the house in the wardrobe), Milan, Italy

- 1945: Sets and costumes for the ballet Mondo Tondo by Ennio Porrino, la Scala, Milan, Italy

- 1946: Objects in papier-mâché in collaboration with Enrico and Gaetano Dal Monte, Faenza, Italy

- 1946–1950: Glass objects for Venini, Murano, Venice, Italy

- 1947: Sets and costumes for Orfeo ed Euridice by Christoph Willibald Gluck, la Scala, Milan, Italy

- 1948: Coffee machine La Cornuta for La Pavoni, Milan, Italy

- 1949: Sewing machine Visetta for Visa, Voghera, Italy

- 1950: Furniture for Singer & Sons, New York City, United States

- 1950–1960: Textiles for Jsa, Busto Arsizio, Varese, Italy

- 1951: Display of a standard hotel room for the IXth Milan Triennial, Milan, Italy

- 1951: 646 Leggera chair for Cassina, Meda, Milan, Italy

- 1951: Conca cutlery and other silver objects for Krupp Italiana, Milan, Italy

- 1953: Furniture and organized walls for Altamira, New York City, United States

- 1953: Furniture for Nordiska Kompaniet department store, Stockholm, Sweden

- 1953: 807 Distex armchair for Cassina, Meda, Milan, Italy

- 1953: Bathroom fittings for Ideal Standard, Milan, Italy

- 1953: Bodywork line Diamante for Carrozzeria Touring, Milan, Italy (project)

- 1953: Sets and costumes for Mitridate Eupatore by Alessandro Scarlatti, Milan, Italy

- 1953–1954: Folding chair for Cassina-Singer, Milan, Italy, later produced by Reguitti, Brescia, Italy

- 1954–1958: Diamante cutlery for Reed & Barton, Newport, Massachusetts, United States

- 1956: Round armchair for Cassina, Meda, Milan, Italy

- 1956: Door handles for Olivari, Borgomanero, Novara, Italy

- 1956: Light fittings for Arredoluce, Milan, Italy

- 1956: Enameled cooper objects and animals in collaboration with Paolo De Poli, Padua, Italy

- 1956–1957: Diamond-shaped tiles and ceramic pebbles for Ceramica Joo, Limito, Milan, Italy

- 1957: 699 Superleggera chair for Cassina, Meda, Milan, Italy

- 1959: Folding chair for Reguitti, Milan, Italy

- 1960: Wall light for Lumi, Milan, Italy

- 1960–1964: Tiling for Ceramica d'Agostino, Salerno, Italy

- 1963: Continuum armchair for Pierantonio Bonacina, Lurago d'Erba, Como, Italy

- 1964: Seat for Knoll International, Milan, Italy

- 1966: Dezza armchairs and divans for Poltrona Frau, Tolentino, Italy

- 1966: Bathroom fittings for Ideal Standard, Milan, Italy

- 1967: The Los Angeles Cathedral, sculpture

- 1967: Polsino lamp for Guzzini, Macerata, Italy

- 1967: Fato lamp for Artemide, Milan, Italy

- 1967: Tableware for Ceramica Franco Pozzi, Gallarate, Italy

- 1968: Novedra armchair for C&B Italia, Novedrate, Italy

- 1968: Triposto furniture for Tecno, Varedo, Italy

- 1970: Apta furniture for Walter Ponti, San Biagio, Mantua, Italy

- 1970: Textiles for Jsa, Busto Arsizio, Varese, Italy

- 1971: Gabriela chair for Walter Ponti, San Biagio, Mantua, Italy, later produced by Pallucco, Preganziol, Treviso, Italy

- 1971: Household linen for Zucchi, Milan, Italy

- 1973: Lamps for Reggiani, Milan, Italy

- 1973–1975: Tiling for Ceramica d'Agostino, Salerno, Italy

- 1978: Objects made from silver leaf in collaboration with Lino Sabattini, Bregnano, Como, Italy

References

[edit]- Celant, Germano (2011). Espressioni di Gio Ponti. Milan: Mondadori Electa. ISBN 9788837078775.

- Crippa, Maria Antonietta; Capponi, Carlo (2006). Gio Ponti e l'architettura sacra. Milan: Silvana editoriale.

- Lamia, Doumato (1981). Gio Ponti (Architecture series—bibliography). Monticello: Vance Bibliographies.

- Fiell, Charlotte; Fiell, Peter (1999). Design of the 20th Century. Cologne: Taschen. ISBN 3-8228-5873-0.

- Green, Keith Evan (2006). Gio Ponti and Carlo Mollino: Post-war Italian Architects and the Relevance of Their Work Today. Lewiston, New York: Edwin Mellen Press.

- Irace, Fulvio (1988). La Casa all'italiana. Milan: Mondadori Electa. ISBN 9788843524495.

- La Pietra, Ugo, Gio Ponti, New York: Rizzoli International, 1996

- Ponti, Lisa Licitra, Gio Ponti, The Complete Work, 1928–1978, Cambridge (Mass.): MIT Press, 1990

- Fabrizio Mautone, Gio Ponti. La committenza Fernandes, Electa Napoli, 2009, ISBN 978-88-510-0603-7

- Gio Ponti, In Praise of Architecture, NY: F.W. Dodge Corporation, 1960. Library of Congress number 59-11727

- Graziella Roccella, Gio Ponti: Master of Lightness, Cologne: Taschen, 2009, ISBN 978-3-8365-0038-8

- Romanelli, Marco; Ponti, Lisa Licitra, eds. (2003). Gio Ponti. A World. Milan: Abitare Segesta.

- Daniel Sherer, "Gio Ponti: The Architectonics of Design," Catalogue Essay for Retrospective Gio Ponti: A Metaphysical World, Queens Museum of Art, curated by Brian Kish, 15 Feb – 20 May 2001, 1–6.

- Daniel Sherer, "Gio Ponti in New York: Design, Architecture, and the Strategy of Synthesis," in Espressioni di Gio Ponti, ed. G. Celant. Catalogue essay for the Ponti Exhibition at the Triennale di Milano, 6 May – 24 July 2011 (Milan: Electa, 2011), 35–45.

- Mario Universo, Gio Ponti designer: Padova, 1936–1941, Rome: Laterza, 1989

Citations

[edit]- ^ Ponti, Gio (February 1961). "Villa Planchart, Caracas 1953–57". domusweb.it. Domus. Retrieved 30 September 2022.

- ^ "North Building". DenverArtMuseum.org. Denver Art Museum. Retrieved 30 September 2022.

- ^ "PALAZZO MONTECATINI". Olivari.it. OLIVARI B. S.P.A. Retrieved 30 September 2022.

- ^ a b c d Ponti, Lisa Licitra (1990). Gio Ponti: l'opera. Ponti, Gio, 1891–1979 (1st ed.). Milano: Leonardo. ISBN 8835500834. OCLC 23017967.

- ^ Ponti, Lisa Licitra (1990). Gio Ponti: l'opera. Ponti, Gio, 1891–1979 (1st ed.). Milano: Leonardo. ISBN 8835500834. OCLC 23017967.

- ^ "Treccani". Treccani.it.

- ^ "The ADI Compasso d'Oro Award". ADI Design Museum. Retrieved 24 September 2022.

- ^ "Compasso d'oro alla carriera (1956)". ADI Design Museum (in Italian). Retrieved 28 July 2024.

- ^ "Gio Ponti – 699 Superleggera". Italian Architecture. Retrieved 24 September 2022.

- ^ "Pónti, Giovanni nell'Enciclopedia Treccani". www.treccani.it (in Italian). Retrieved 24 September 2022.

- ^ Fiell, Charlotte; Fiell, Peter (2005). Design of the 20th Century (25th anniversary ed.). Köln: Taschen. p. 562. ISBN 9783822840788. OCLC 809539744.

- ^ a b Graziella, Roccella (2017). Gio Ponti 1891–1979: master of lightness (English ed.). Köln. ISBN 9783836564397. OCLC 1025334052.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Mussolini claimed on 28 October 1932, that "non si può superare il divino con l'umano" (We cannot exceed the divine with the human).

- ^ Lombardia Beni Culturali

- ^ Lucia, Miodini (2001). Gio Ponti: gli anni trenta. Milano: Electa. ISBN 8843577042. OCLC 49874443.

- ^ "Scuola di Matematica". Archi DiAP. Retrieved 4 August 2017.

- ^ a b Il miraggio della concordia: documenti sull'architettura e la decorazione del Bo e del Liviano: Padova 1933–1943. Nezzo, Marta (1966– ). [Treviso]: Canova. 2008. ISBN 9788884092052. OCLC 310391604.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ GMGprogettocultura (2016). Arte sulle motonavi: il varo dell'utopia. Chioggia: Il Leggio Libreria editrice.

- ^ Brevini, Franco (1951– ) (2005). Grattacielo Pirelli: un capolavoro di Gio Ponti per la Lombardia. Milano: Touring club italiano. ISBN 8836533825. OCLC 58466940.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Gio Ponti: la Villa Planchart a Caracas = Gio Ponti: Villa Planchart en Caracas. Ponti, Gio (1891–1979); Greco, Antonella; Rubini, Rubino. Roma: Kappa. 2008. ISBN 9788878909007. OCLC 234368228.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b Romanelli & Ponti 2003, p. 6.

- ^ "Il pellegrino stanco by Gio Ponti by Salvatore Saponaro | Blouin Art Sales Index". www.blouinartsalesindex.com. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- ^ "Il Novecento – Salvatore Saponaro". www.edixxon.com. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- ^ Ponti, Gio (1891–1979) (2015). Gio Ponti: la collezione del Museo Richard-Ginori della manifattura di Doccia = Gio Ponti: the collection of the Museo Richard-Ginori della manifattura di Doccia. Frescobaldi Malenchini, Livia; Giovannini, Maria Teresa; Rucellai, Oliva; Museo Ginori di Doccia. [Falciano]. ISBN 9788898855339. OCLC 929450430.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ La Pietra, Ugo (2009). Gio Ponti, l'arte si innamora dell'industria. Milan: Rizzoli.

- ^ Franco, Deboni (2013). Fontana Arte: Gio Ponti, Pietro Chiesa, Max Ingrand. Turin. ISBN 9788842222163. OCLC 881689184.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c Fulvio, Irace (2011). Gio Ponti. Ponti, Gio (1891–1979). Milano: 24 ore cultura. ISBN 9788861161382. OCLC 746301220.

- ^ Mauriès, Patrick, (1952– ) (2015). Piero Fornasetti: la folie pratique. Paris: Les Arts décoratifs. ISBN 9782916914558. OCLC 905906425.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Made in Cassina. Bosoni, Giampiero. [Paris]: Skira-[Flammarion]. 2008. ISBN 9782081219205. OCLC 470583524.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ BBCC. "Architetto e Designer Giovanni Ponti è nato oggi". www.beniculturalionline.it. Retrieved 24 September 2022.

- ^ Fiell, Charlotte; Fiell, Peter (2017). Domus: 1928–1939. Fiell, Charlotte, 1965– , Fiell, Peter; Irace, Fulvio. Köln. ISBN 978-3836526524. OCLC 929918224.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Design Museum: Gio Ponti Biography

- ^ "Gio Ponti". designboom.com. Archived from the original on 6 February 2012. Retrieved 3 November 2011.

External links

[edit]- Gio Ponti's works on the Italian public Television – RAI

- Gio Ponti Archives – Official Website

- INA Casa Harrar-Ponti by Gio Ponti in Rome (1951–1955) (with drawings and photos)

- Gio Ponti's inventions on Architonic Archived 7 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- 1891 births

- 1979 deaths

- 20th-century Italian architects

- Italian fascist architecture

- Modernist designers

- Italian furniture designers

- Italian military personnel of World War I

- Italian industrial designers

- Architects from Milan

- Polytechnic University of Milan alumni

- Academic staff of the Polytechnic University of Milan

- Commanders of the Order of Vasa

- Modernist architects from Italy

- Italian magazine editors

- Italian magazine founders

- Compasso d'Oro Award recipients

- Domus (magazine) editors