Harry S. Truman 1948 presidential campaign

| Harry S. Truman 1948 presidential campaign | |

|---|---|

| |

| Campaign | |

| Candidate |

|

| Affiliation | Democratic Party |

| Status |

|

| Key people |

|

| Slogan | Give 'em hell, Harry! |

| Theme song | "I'm Just Wild About Harry" |

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Senator from Missouri

33rd President of the United States First term Second term Presidential and Vice presidential campaigns Post-presidency  |

||

In 1948, Harry S. Truman and Alben W. Barkley were elected president and vice president of the United States, defeating Republican nominees Thomas E. Dewey and Earl Warren. Truman, a Democrat and vice president under Franklin D. Roosevelt, had ascended to the presidency upon Roosevelt's death in 1945. He announced his candidacy for election on March 8, 1948. Unchallenged by any major nominee in the Democratic primaries, he won almost all of them easily; however, many Democrats like James Roosevelt opposed his candidacy and urged former Chief of Staff of the United States Army Dwight D. Eisenhower to run instead.

Truman wanted U.S. Supreme Court Associate Justice William O. Douglas to be his running mate. Douglas declined, claiming a lack of political experience; in reality, his friend Thomas Gardiner Corcoran had advised him not to be a "number two man to a number two man".[1] Senator Barkley's keynote address at the 1948 Democratic National Convention energized the delegates and impressed Truman, who then selected Barkley as his running mate. When the convention adopted Truman's civil rights plank in a close vote of 651+1⁄2 to 582+1⁄2, many Southern delegates walked out of the convention. After order was restored, a roll call vote gave Truman a majority of delegates to be the nominee; Barkley was nominated the vice-presidential candidate by acclamation.

The Progressive Party nominated Henry A. Wallace, a former Democratic vice president, to run against Truman. Strom Thurmond, the governor of South Carolina, who had led a walkout of a large group of delegates from Mississippi and Alabama at the 1948 convention, also ran against Truman as a Dixiecrat, campaigning for states' rights. With a split of the Democratic Party, most polls and political writers predicted victory for Dewey and gave Truman little chance.

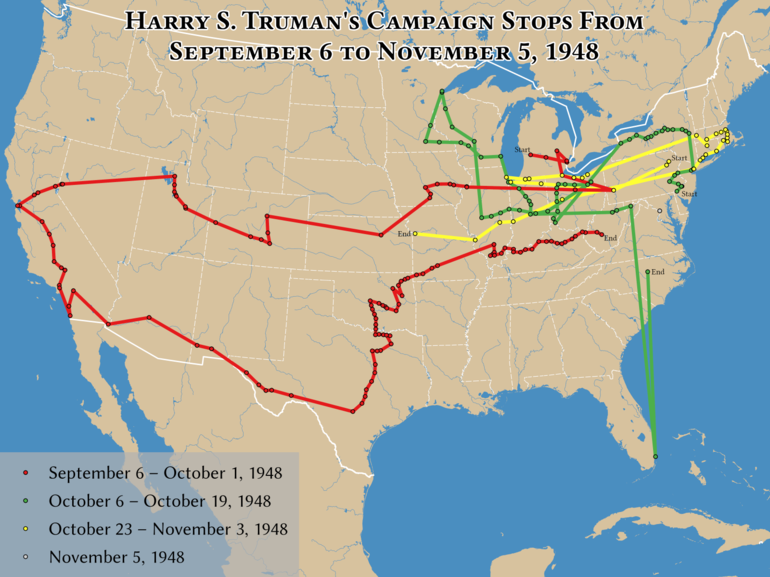

During the campaign, Truman mostly focused on blaming the Republican-controlled Congress for not passing his legislation, calling it a "do-nothing Congress." In early September 1948, Truman conducted various whistle-stop tours across the nation, covering over 21,928 miles (35,290 km) on the Ferdinand Magellan railcar. Of all of the speeches which he gave during his whistle-stop tour, only about 70 were broadcast on the radio even locally, and only 20 of them were heard nationally. During the final days of the campaign, the Truman campaign released a film titled The Truman Story showing newsreel footage of the whistle-stop tour. Although he received some endorsements, including that of Screen Actors Guild president Ronald Reagan, most broadcasting companies were sure of Dewey's victory. Ultimately, Truman won with 303 electoral votes to Dewey's 189 and Thurmond's 39. Before the results were released, an early edition of the Chicago Daily Tribune wrongly anticipated the result with the headline "Dewey Defeats Truman". Time magazine later described an image of Truman holding the newspaper as the "greatest photograph ever made of a politician celebrating victory."[2] Truman and Barkley were inaugurated on January 20, 1949. Truman's 1948 campaign and the election are most remembered for the failure of polls and Truman's upset victory.

Background

[edit]Harry S. Truman was born in Lamar, Missouri, in 1884.[3] After graduating from Independence High School in 1901, he enrolled at the Spalding's Commercial College, but dropped out within a year.[4] When the United States entered World War I in 1917, Truman joined Battery B, successfully recruiting new soldiers for the expanding unit, for which he was selected as their first lieutenant.[5] By July 1918, he became commander of the newly arrived Battery D of the 129th Field Artillery, 35th Division.[6] After the war, he was elected the Presiding Judge of Jackson County, Missouri, and later served as a senator from Missouri.[7] As a senator, he was head of the Senate Special Committee to Investigate the National Defense Program, known as the Truman Committee.[8][9]

By 1944, most of the advisors of the incumbent President Franklin D. Roosevelt believed that he might not live out a fourth term and that his vice president would likely become the next president. Most of Roosevelt's advisors viewed the incumbent Vice President Henry A. Wallace as too liberal.[10] In 1944, Roosevelt replaced Wallace from his ticket with Truman.[11] Despite showing little interest in being vice president, Truman was selected by the 1944 Democratic National Convention as the nominee. The Roosevelt–Truman ticket won the presidential election, defeating the Republican ticket of Thomas E. Dewey and John W. Bricker.[12] Truman was sworn in as vice president on January 20, 1945. He had been vice president for 82 days when Roosevelt died on April 12, making Truman the 33rd president.[13] Truman later said: "I felt like the moon, the stars, and all the planets had fallen on me."[14]

Truman asked Roosevelt's cabinet members to remain in their positions, telling them he was open to their advice. He emphasized a central principle of his administration: he would be the one making the decisions, and they were to support him.[15] During World War II, with the invasion of Japan imminent, he approved the schedule for dropping two atomic bombs to avoid a costly invasion of the Japanese mainland. It had been estimated the invasion could take a year and cause 250,000 to 500,000 American casualties. The United States bombed Hiroshima on August 6, and Nagasaki three days later, leaving approximately 105,000 dead;[16][17] Japan agreed to surrender the following day.[18] Truman said that attacking Japan in this way, instead of invading it, saved many lives on both sides. With the end of World War II, Truman implemented the Marshall Plan, allocating foreign aid for Western Europe. Apart from primaries and campaigning in 1948, Truman dealt with the Berlin Blockade, which is considered the first major diplomatic crisis of the Cold War.[19] During Truman's presidency, his approval ratings had dropped from 80 percent in early 1945 to 30 percent in early 1947. The 1946 mid-term election alarmed Truman when Republicans won control of both houses of Congress for the first time since the 1920s.[20] In 1947, Truman told his Secretary of Defense James Forrestal that, except for the "reward of service", he had found little satisfaction in being president.[21]

Gaining the nomination

[edit]Preparing for a run

[edit]In December 1947, former Vice President Wallace had announced via radio that he would seek the presidency in 1948 as a third-party candidate. He was dissatisfied with Truman's foreign policy, and in his announcement, made an attempt to link Truman to a war-oriented point of view. The previous year, Truman had demanded and received his resignation from the cabinet as the Secretary of Commerce.[22] Due to his declining popularity, Truman had initially decided not to run.[23] He considered former Chief of Staff of the Army General Dwight D. Eisenhower as an ideal candidate for the Democrats, and persuaded him to contest the presidency. In a public statement, however, Eisenhower declined all requests to enter politics, without disclosing his political party affiliation.[24][25] Momentum among Americans for Democratic Action (ADA) members and politicians grew for the Draft Eisenhower movement – to the extent that some Democratic politicians began organizing a "Dump Truman" effort to persuade Eisenhower to run as a Democrat.[26] According to Secretary of the Army Kenneth Royall, Truman even agreed to run as the vice-presidential nominee of Eisenhower, if he so desired, but all efforts to persuade him failed.[21]

In early 1948, Truman agreed to contest the presidency, asserting that he wanted to continue contributing to the welfare of the country.[24] His advisor, Clark Clifford, later said that the greatest ambition Truman had was to be elected in his own right. His candidacy faced opposition within the Democratic Party from the progressive movement led by Wallace, and the states' rights movement led by South Carolina Governor Strom Thurmond.[27] In November 1947, Democratic political strategist James H. Rowe wrote a memo titled "The Politics of 1948", highlighting the challenges and the road map for Truman's campaign.[28] Clifford edited and presented the forty-three page confidential memo to Truman,[29][28] which stated: "The Democratic Party is an unhappy alliance of Southern conservatives, Western progressives, and Big City labor."[30] Rowe accurately predicted Dewey would win the Republican nomination, calling him a "resourceful, intelligent and highly dangerous candidate".[30] Rowe also warned of the potential threat from Southern Democrats and Wallace.[30] The Rowe–Clifford memo advised Truman to project himself as a strong liberal and focus his campaign primarily on urban blacks, labor, and farmers – who made up the core of the New Deal coalition.[31] Although Truman did not trust Rowe because of their difference of opinion in the past,[28] he endorsed the strategy.[31]

In his 1948 State of the Union address, Truman emphasized civil rights, saying: "Our first goal is to secure fully the essential human rights of our citizens."[32] On March 8, 1948, Democratic National Committee Chair J. Howard McGrath officially declared Truman's candidacy.[33] He said: "The president has authorized me to say, that if nominated by the Democratic National Convention, he will accept and run." [34] The presidential primary contests began the next day with the New Hampshire primary.[35] Truman won the support of all unpledged delegates unopposed. He faced little opposition in the primary contests, as he was the sole major contender. He won almost all the contests by comfortable margins, receiving approximately 64 percent of the overall vote.[35] Despite his performance in the primaries, Gallup Poll indicated no matter how Truman might campaign, he would lose in November to any of four possible Republican nominees: Dewey, Arthur Vandenberg, Harold Stassen, or Douglas MacArthur.[36]

Historian and author Andrew Busch described the political scenario as:

Americans in 1948 had to render judgment on three major policy innovations. It was the first presidential election since depression, war, and the presence of FDR in which the nation could take stock of the New Deal direction of domestic policy. It was also the first election after the establishment of containment as the foreign policy of the United States and the first since Truman had made civil rights an important part of the federal policy agenda ... The presidential nominating system in 1948 was substantially different from the reformed system to which we are accustomed, and the differences were important. Primary elections influenced the nomination but did not control it; it was possible to seriously consider a genuine last-minute draft of a candidate; and the national conventions really mattered.[37]

Early developments

[edit]In early June, the University of California, Berkeley invited Truman to accept an honorary doctorate. Truman converted his California trip to a whistle-stop train tour through eighteen strategic states, campaigning from June 3.[38] The president's discretionary travel fund covered the costs because of a lack of donations to the Democratic National Committee.[39][40] Truman referred to it as a "non-political trip".[41] He focused on the eightieth Congress in his speeches, referring to it as "the worst congress".[42] As his tour progressed, the crowds grew significantly, from approximately a thousand in Crestline, Ohio, to a hundred thousand in Chicago, Illinois.[43] In Omaha, Nebraska, Truman's address at the Ak-Sar-Ben auditorium to the veterans of the 35th Division has been referred to as an embarrassment.[44][45] The auditorium had a capacity of ten thousand, but fewer than two thousand attended. Organizers failed to publicize that the auditorium was open to the public and not just veterans of the 35th Division.[46] Newspapers printed images of the nearly vacant auditorium, and columnists interpreted this as a further sign of Truman's dwindling popularity.[47] The same day, Truman watched a parade in his presidential car with Roy J. Turner, the governor of Oklahoma. When Battery D of the 129th Field Artillery passed by, Truman joined the veterans of his World War I military unit and marched with them for half a mile.[48] Two days later at Los Angeles, an estimated one million people gathered on Truman's way from the railroad station to the Ambassador Hotel. The Los Angeles Times reported that the crowd "clung to the roofs of buildings, jammed windows and fire escapes and crowded five deep along the sidewalk".[49]

Although Truman ran mostly unopposed in the primaries, the "Eisenhower craze" was in full swing among some Democrats a few weeks before the convention.[25] Franklin D. Roosevelt's son, James Roosevelt, campaigned for Eisenhower to contest the nomination and take Truman's place on the ticket.[50] Despite several refusals, Eisenhower was still being pursued by various political leaders.[25] Several polling agencies suggested Eisenhower was likely to defeat Dewey if he ran in place of Truman. Reacting to this at a news conference on July 1, Truman said he would not withdraw his candidacy even though no one had seriously challenged him in a single Democratic primary.[25] Still, Roosevelt made no secret of his intention to prevent Truman from becoming the nominee. Truman once told Roosevelt: "If your father knew what you were doing to me, he would turn over in his grave."[50]

With the convention approaching, Truman still had to decide on a running mate. He wanted one younger than him and strong on liberal issues. His initial choice was Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas.[51] Douglas was also the alternative candidate for most of the Eisenhower supporters, but he declined, claiming a lack of political experience; he also wanted to remain in the Supreme Court.[52] His friend Thomas Gardiner Corcoran had suggested him not to be a "number two man to a number two man".[1] A week before the convention, Roosevelt sent telegrams to all 1,592 delegates voting for the party nomination, asking them to arrive in Philadelphia two days early for a special Draft Eisenhower caucus attempting to make a strong joint appeal to Eisenhower.[53] Columnist Drew Pearson wrote: "If the Democrats failed to get Ike [Eisenhower] to run, every seasoned political leader in the Democratic Party is convinced Harry Truman will suffer one of the worst election defeats in history."[54] Humiliated by the draft, Truman called Roosevelt a "Demo-republican" and "double-dealer".[54] After Eisenhower declined to run yet again, various ADA members unsuccessfully tried to persuade Douglas to contest the nomination,[55] but many Truman supporters soon believed that Truman would be chosen as the Democratic nominee.[56][57]

Democratic convention

[edit]

The 1948 Democratic National Convention convened at the Philadelphia Convention Hall in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, from July 12 to July 15. The crowd was smaller than the Republican National Convention held a few weeks earlier.[58] Some delegates carried banners with the slogan "Keep America Human with Truman".[59] Viewing the first televised Democratic National Convention from the White House, Truman heard Senator Alben W. Barkley of Kentucky deliver a keynote address that energized the delegates in the convention hall.[60] After his speech, some delegates broke into a spontaneous demonstration and marched around the hall singing "My Old Kentucky Home" carrying banners inscribed with "Barkley for Vice-President".[61] When Senator Howard McGrath asked Truman his views on the speech, Truman replied: "If Barkley is what the convention wanted for the vice presidency, then Barkley is my choice too."[62] At 71, Barkley was older than Truman, and from Kentucky, neither of which helped to counteract the issue of Truman's age, nor bring a geographical balance to the ticket.[62] Barkley, however, was immensely popular within the Democratic Party, and political experts wrote that his presence on the ticket would help to cement the fractious Democratic coalition.[63] The following day, Truman called Barkley asking him to be his running mate, saying: "If I had known you wanted it the vice presidency, I certainly would have been agreeable."[62] Barkley agreed to be his running mate.[62]

July 14 was scheduled for Truman's nomination and his acceptance speech. Before his arrival, the Southern delegates were agitated when the convention adopted Truman's civil rights plan, which supported equal opportunity in employment and in the military.[64][65] Although Truman did not intend to alienate the South,[66] many Southern delegates from Mississippi were sent with binding instructions to leave the convention if it did not endorse the states' rights plank.[67] Soon after Senator Francis J. Myers read the civil rights plank, many Southern delegates rose in protest.[66] They demanded the convention to endorse their states' rights plank, which specifically called for the power of states to maintain segregation.[68] The convention adopted the civil rights plank in a vote of 651+1⁄2 to 582+1⁄2. Hubert Humphrey tried to control the situation with his "The Sunshine of Human Rights" address, saying: "We are not rushing on civil rights, we are 172 years late."[69][70] Soon after, Thurmond led a walkout of a large group of delegates from Mississippi and Alabama, yelling "Goodbye Harry".[65]

The Washington Post's correspondent Marquis Childs later called the walkout of delegates the "liquidation of one of the major parties".[71] Shortly after order was restored, Charles J. Bloch, a delegate from Georgia, shouted: "The South is no longer going to be the whipping boy of the Democratic Party," and called for the nomination of Senator Richard Russell as an alternative to Truman.[65][72] The remaining delegates then voted for presidential nomination, which formally made Truman the Democratic nominee, with 947+1⁄2 delegates to Russell's 266.[73][74][75] Although many remaining Southern delegates voted for Russell, a split vote in South Carolina gave the victory to Truman.[76] Barkley was nominated as the vice-presidential nominee by acclamation.[73] Truman was expected to deliver his acceptance speech at 10:00 p.m., but because of the walkout by some delegates the convention was behind schedule, and he did not give his speech until 2:00 a.m. on July 15.[77] Truman began his speech, electrifying the delegates by directly attacking the Republican platform, and praising Barkley – who was considered the most popular man in the hall.[78] He said:

I accept the nomination. And I want to thank this convention for its unanimous nomination of my good friend and colleague, Senator Barkley of Kentucky. He is a great man, and a great public servant. Senator Barkley and I will win this election and make these Republicans like it – don't you forget that! We will do that because they are wrong and we are right, and I will prove it to you in just a few minutes.[79][80]

He blamed the Republican-controlled Congress for not passing various of his legislative measures.[81] Although he did not mention his opponent Dewey, he criticized the Republican platform, contrasting them for actions of the eightieth Congress.[82] He said that he would call Congress back into session on July 26th, Turnip Day,[a] to pass legislation ensuring civil rights and social security and establishing a national healthcare program. "They [Congress] can do this job in fifteen days if they want to do it," he challenged.[84] The session came to be known as the Turnip Day Session.[84] Describing his reference of the eightieth Congress, Newsweek reported: "Nothing short of a stroke of magic could infuse the remnants of the party with enthusiasm, but the magic he had; in a speech bristling with marching words, Mr. Truman brought the convention to its highest peak of excitement."[82] American author and historian David Pietrusza later wrote that Truman's speech transformed a "hopelessly bedraggled campaign" into an "instantly energized effort capable of ultimate victory in November".[85] He referred to the speech as the first great political speech of the television era, and wrote that it moved politics from the radio age to the "ascendancy of the visual, propelling images as well as words immediately into the homes of millions of Americans".[85]

Campaign

[edit]It will be the greatest campaign any President ever made. Win, lose, or draw, people will know where I stand.

— Harry S. Truman[86]

Initial stages

[edit]

Soon after the convention Truman stated that the whole concept of his campaign was to motivate voters and galvanize support for the candidate and the party.[87] Republicans charged Truman with crude politics asserting his call for a special session of Congress was the "act of a desperate man".[88] Rather than directly attacking Dewey, Truman sought to continue blaming the Republican-controlled Congress.[87] On July 17, the Southern delegates who bolted the Democratic Convention convened and nominated Thurmond as the official States' Rights Democratic Party presidential nominee, with Fielding L. Wright, the governor of Mississippi, as their vice-presidential nominee.[89] They were soon nicknamed "Dixiecrats", and were perceived as a minor party having strong influence in the South.[90]

With the split within the Democratic Party, many pollsters believed Truman had little chance of winning. The initial issue Truman had to deal with was financing the campaign. The Democratic National Committee's funds were insufficient.[91] Moreover, the Dewey campaign had released a collection of quotes from a few well-respected Democratic politicians saying that Truman could not win, reducing the number of donors. A meeting was held at the White House on July 22 to form the campaign finance committee. Truman stated he would travel all over the country after Labor Day, and address every stop on the tour to campaign and raise money.[92] Soon after, the Democratic National Committee moved its headquarters from Philadelphia to New York City.[93]

Louis A. Johnson was named the campaign fundraiser and the finance chairman for the Democratic National Committee.[94] With Truman's declining polling numbers, Johnson's fundraising was crucial for the campaign. William Loren Batt, a member of Combined Munitions Assignments Board, headed a new campaign research unit formed to focus on local issues and trends in the cities where Truman was expected to give speeches.[95] A day before the special session of Congress, the Progressive Party formally nominated Wallace as their presidential nominee, with Glen H. Taylor, a senator from Idaho, as his running mate.[96]

Truman's close friend Oscar Ewing advised him to take his civil rights plan to its next logical step by desegregating the military by executive order rather than passing it through Congress.[97] Considering the suggestion to be a dangerous move, Truman initially hesitated, asserting that Southern Democrats would oppose it.[97] Ultimately, on July 26, 1948, Truman signed Executive Order 9980 creating a system of "fair employment practices" within the federal government without discrimination because of race, color, religion or national origin; and Executive Order 9981 re-integrating the segregated Armed Forces.[98] The following day, in the special session of Congress, he called for action on civil rights, economy, farm support, education, and housing development.[99][100] Republican legislators strongly opposed these measures, but the Dewey campaign partially supported Truman's civil rights plan, trying to separate themselves from the conservative record of Congress.[101] On July 31 Truman and Dewey met for the first and only time during the campaign at the dedication of Idlewild Airport (now John F. Kennedy International Airport) in New York City.[102] After speeches were given by both the major party candidates, Truman humorously whispered to Dewey: "Tom, when you get to the White House, for God's sake, do something about the plumbing."[103]

Truman selected the 1921 popular song "I'm Just Wild About Harry" as his campaign song.[104] His opponents mockingly sang the parody song, with the title "I'm Just Mild About Harry".[105] In early August, when the special session of Congress was about to end, Truman claimed in his weekly press conference that the eightieth Congress had failed to pass legislation he had proposed to curb inflation.[106] When a reporter asked him, "Do you think it [Congress] had been a 'do-nothing' Congress?" Truman replied, "Entirely".[107] In a memo to Clark Clifford, Batt provided an overview of events and challenges that the Truman campaign might face. He suggested Truman to campaign in close contact with voters both in August and after Labor Day in September.[108] At the outset of the fall campaign, Truman's advisers urged him to focus on critical states decided by narrow margins in 1944, and make his major addresses in the twenty-three largest metropolitan areas. It was decided he should make three long campaign tours – one each through the Midwest, the far West, and the Northeast – and a shorter trip to the South.[109]

Whistle-stop tour

[edit]Truman formally began his campaign on Labor Day with a one-day tour of Michigan and Ohio. In a speech at Grand Rapids, Michigan, he attacked Republicans, claiming that few "special privilege" groups controlled them.[110] Grand Rapids was a Republican stronghold, yet around 25 thousand people attended to listen to him.[110] His six stops in Michigan drew approximately half a million people.[111] On September 13, a fundraiser was held at the White House with about 30 invited potential donors. Truman asked them for help, saying his campaign did not have the funds to buy radio time, and often had to cut an important part of a speech as a result.[112] He began his whistle-stop tour in an 83-foot (25 m) private armored railway car called the Ferdinand Magellan on September 17.[113] While boarding the train, Senator Barkley asked him if he was to carry the fight to the Republicans, to which Truman replied: "We're going to give 'em hell".[113]

Apart from Truman and his campaign team, about a hundred other officials boarded the train, including many journalists.[114] Clifford, David Bell, George Elsey, and Charles Murphy were responsible for writing Truman's major speeches.[115] The tour was divided into three segments – first cross-country to California for fifteen days, a six-day tour of the Middle West, followed by a final ten days in the Northeast with a return trip to Missouri. Initially, Truman planned to travel in all 48 states but later decided to campaign only in swing states and Democratic-leaning states, avoiding Deep South states that heavily favored Dixiecrats.[116]

The train departed on September 17 from Pittsburgh, and headed west. The first major stop was in Dexter, Iowa, where Truman delivered a speech on September 18 at the National Plowing Contest.[117] He called the Republican Party "gluttons of privilege", and said the Democratic Party represents the common people. He said: "I'm not asking you to vote for me, vote for yourselves, vote for your farms, vote for the standard of living you have won under a Democratic administration."[118] Meanwhile, Dewey was also conducting a whistle-stop tour on his train titled the "Dewey Victory Special".[119] Thousands attended his speeches, but author Zachary Karabell wrote that the crowd could hardly be called excited; they had no intensity or sense of the importance of the moment.[120] While campaigning, both major candidates did not mention each other by name, but attacked the other's platform. Truman continued blaming the "do nothing" Congress and called Republicans a special-interest group.[121] Author Donald R. McCoy observed that: "[Truman's] voice was flat and nasal, his prepared texts were often stilted, and his gestures were limited to chopping hand motions, which were not always appropriate to what he was saying."[122]

During a speech in Salt Lake City, he said: "Selfish men have always tried to skim the cream from our natural resources to satisfy their own greed. And ... [their] instrument in this effort has always been the Republican Party."[121] In a busy schedule, Truman delivered four or five speeches a day.[123] Most of the train stops featured a local brass band that played "Hail to the Chief" or the "Missouri Waltz".[124] Robert Donovan, a correspondent at the New York Herald Tribune, later characterized Truman's campaign as "sharp speeches fairly criticizing Republican policy and defending New Deal liberalism".[125] In shorter speeches of about ten minutes, he praised and endorsed the local candidate for congressional election, and gave the rest of the speech covering local and general topics.[126] The size of the crowd increased in each subsequent town as people started seeing Truman as a fearless underdog.[127] His speeches were not covered extensively by radio or television. During one speech, a man from the crowd yelled, "Give 'em hell, Harry!", as the news accounts of his promise to Barkley spread across the country.[126] Truman replied: "I don't give them Hell. I just tell the truth about them, and they think it's Hell."[128] Soon after, many people started yelling and repeating "Give 'em hell, Harry!", which by late September had become a well-known campaign slogan.[127]

While Truman campaigned on the train, Senator Barkley traveled by airplane and campaigned across the nation, though he also avoided campaigning in the Deep South.[129] While addressing a crowd of about a hundred thousand on September 28 in Oklahoma, Truman answered the Republican charges of communism in government. He called that the charges were a "smoke screen" of Republican tactics to hide their failure to deal with other issues.[130] Considering the importance of a speech and its effect on the campaign, the Democratic National Committee decided to pay for nationwide radio time. The next day, Truman gave his hundredth speech from the rear platform of the train. He spoke at sixteen stops, addressing more than half a million people.[131]

During the early days of October, Truman kept his specific attacks on the Congress, backed up with the daily facts supplied by Batt's research team.[132] On October 11, he gave eleven speeches at different stops over fifteen hours.[133] While addressing a crowd at Springfield, Illinois, the next day, he claimed Democrats to be "practical folks", and said that Republicans are afraid to tell the people their stand on specific issues. He remarked: "The Republicans know they can't run on their record – that record is too bad. But you ought to know about their record. And since they won't tell you, I will."[134]

In his letter to his sister, Mary Jane, Truman asserted his firm belief in their victory. He wrote: "We've got 'em on the run and I think we'll win."[135] By the end of his tour, he had delivered 352 speeches covering 21,928 miles (35,290 km).[116][136][137] Truman campaigned much more actively than Dewey. Although the candidates had only a slight difference in the number of states visited, Truman had a clear lead in the number of campaign stops, having made 238 stops to Dewey's 40.[b][139]

1 – cross-country to California (Red)

2 – tour of the Middle West (Green)

3 – final ten days in the Northeast with a return trip to Missouri (Yellow)

Media and polls; the final days

[edit]

As Truman's whistle-stop tour continued the size of the crowd increased. The large, mostly spontaneous gatherings at Truman's whistle-stop events were an important sign of a change in the campaign's momentum, but this shift mostly went unnoticed by polling agencies.[140] Except for Louis H. Bean and Survey Research Center's (SRC) polls, most of the other polls conducted during the fall campaign polled Dewey having a decisive lead over Truman.[141][142] Dewey's campaign strategy was to avoid major mistakes and act presidential, which likely helped keep his polling numbers high.[143] Elmo Roper, a major pollster, announced that his organization would discontinue polling since it had already predicted Dewey's victory by a large majority of electoral votes.[144] He said that his whole inclination was to predict Dewey's victory by a heavy margin, and wanted to devote his time and efforts in other things.[145] His latest poll showed Dewey leading by an "unbeatable" 44 percent to Truman's 31 percent.[144]

In early October, when Newsweek in an election survey asked fifty major political writers their prediction, all of them chose Dewey to win.[146] When Truman read the article, he said: "I know every one of these fifty fellows. There isn't a single one of them has enough sense to pound sand in a rat hole."[147] Truman's wife, Bess Truman, was doubtful of Truman's victory, and even asked White House aide Tom Evans: "Does he [Truman] really think he can win?"[148] Editors of major media corporations predicted that, in the wake of the expected Democratic defeat nationally, the South would regain its influence in the Democratic Party.[149]

Of all the speeches Truman gave in September and October, only about seventy were broadcast on the radio even locally; twenty were heard nationally.[150] The New York Herald Tribune reported: "The voters are turning out to see the President of the United States; turning out in larger numbers than they will see candidate Dewey."[151] Most of the major newspapers like The New York Times, the Los Angeles Times, and The Washington Star endorsed Dewey.[146] The only major editorial endorsing Truman was in The Boston Post, under the heading "Captain Courageous".[152] The Boston Post called Truman "humbly honest, homespun and as doggedly determined to do what is best for America as Abraham Lincoln".[152] Truman arrived back at the White House in early October and conducted some meetings with the Democratic National Committee's research division.[153]

On October 3, Truman met with the campaign team to discuss strategy and concluded that the campaign needed a new approach to illustrate his effort for peace and security in the world.[153] He decided to send Chief Justice Fred M. Vinson on a diplomatic mission to Moscow attempting to negotiate an end to the Cold War with Soviet premier Joseph Stalin. Vinson initially disagreed, asserting that members of the court should confine themselves to their duties, especially in an election year, but he finally agreed to go.[154] As soon as the news of Truman's "Vinson mission" was released, several of his advisors, including Clifford and Elsey, vehemently opposed it, resulting in Truman immediately withdrawing the plan.[155]

Several editors and columnists accused Truman for appeasing the Soviet Union by using foreign policy for political gain.[156] Time magazine wrote: "His attempted action was shocking because it showed that he had no conception whatever of the difference between the President of the United States and a U.S. politician."[156] Even many Democrats strongly anticipated a victory for Dewey and did not campaign to obtain votes for Truman.[157] On October 10, Truman continued with the final segment of his whistle-stop tour by visiting rural counties in Ohio, Indiana, and Wisconsin.[158] The same day, he received a telegram from Thurmond insisting on a debate, but Truman's campaign ignored it as Thurmond's polling numbers were under two percent, even less than Wallace.[159] The next day, Dewey also went on a seven-day tour of the Midwest.[160] With no policies from Dewey to rebut, Truman focused on making campaign promises.[161] As his tour progressed, a crowd of several thousand waited hours for Truman at various stops.[162] Assured of his victory, Truman said that there are going to be "a lot of surprised pollsters".[163] His direct approach stood out more favorably compared to Dewey's strategy. Truman discussed specific issues and solutions, while Dewey mostly discussed general problems.[157]

It is not just a battle between two parties. It is a fight for the very soul of the American government.

With two weeks to election day, polls showed Dewey's lead reduced by six percent, yet polling within the Truman campaign showed Truman winning with 340 electoral votes to Dewey's 108 and Thurmond's 42.[165] Truman moved closer to the progressive left, drawing crowds with Wallace's message.[166] At the packed Chicago Stadium, he delivered a speech to a crowd of 24,000, considered to be his most influential speech during the campaign.[167] One author of the speech, David Noyes, later said that its aim "was to provoke Dewey into fighting back, a strategy Truman accepted".[167] Days before the election, he campaigned in Massachusetts at various stops attended by millions of people.[168] The campaign team released a film called The Truman Story on October 27, using existing newsreel footage of his whistle-stop tour. It was an instant success compared to The Dewey Story, released by the Republican campaign team.[169] On October 31, two days before election day, former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt urged voters to vote for Truman in a nationally broadcast radio address. Soon after, various leading authors, including Nobel Prize winner Sinclair Lewis, endorsed Truman.[140] The president of Screen Actors Guild, Ronald Reagan, also endorsed him, saying he was "more than a little impatient with those promises the Republicans made before they got control of Congress a couple of years ago".[170]

Election day

[edit]

On the afternoon of election day, Truman went to the Elms Hotel to stay away from the media; only his family and the Secret Service knew his location.[171] Assured of Dewey's victory, the head of the Secret Service, James Maloney, reached New York to provide security to him. About 9:00 p.m., just before Truman was about to retire, he called his advisor Jim Rowley to his room, and asked to be wakened if anything important happened.[172] Initial counting showed Truman leading in the popular vote,[173] but news commentators predicted a Dewey victory.[174] Sometime near midnight, Truman woke up, switched on the radio, and heard the National Broadcasting Company commentator H. V. Kaltenborn saying: "Although the president is ahead by 1,200,000 votes, he is undoubtedly beaten."[175] At four in the morning, Rowley woke Truman saying "We've won!"[176] At 9:30 a.m. he was declared the winner in Illinois and California.[177]

Truman received 303 electoral votes to Dewey's 189 and Thurmond's 39.[178][179] He narrowly carried Ohio, Illinois, and California, the three most crucial states to both the campaigns. He won 28 states and 49+1⁄2 percent of the popular vote.[180][181] In congressional races, Democrats won control of both the houses with 54 Senate seats for the Democrats and 42 for the Republicans. In the House of Representatives the Democratic victory was overwhelming: 263 seats to 171.[182] In an upset defeat, Dewey officially conceded at 11:00 a.m. on November 3. Truman's triumph astonished the nation and most of the pollsters. On its cover Newsweek called Truman's victory startling, astonishing and "a major miracle".[183] Truman became the first candidate to lose in a Gallup Poll but win the election.[184] His close friend Jerome Walsh recalls Truman on the election night:

He [Truman] displayed neither tension nor elation. For instance someone remarked bitterly that if it hadn't been for Wallace, New York and New Jersey would have gone Democratic by good majorities. But the President dismissed this with a wave of his hand. As far as Henry was concerned, he said, Henry wasn't a bad guy; he was doing what he thought was right and he had every right in the world to pursue his course.[185]

In his victory speech on November 3, he called it "a victory by the Democratic party for the people". An early edition of the Chicago Daily Tribune had printed the headline DEWEY DEFEATS TRUMAN, boldly anticipating a victory for Dewey.[2] On November 4 Truman stepped out onto the rear platform of the Ferdinand Magellan during a brief stop in St. Louis, Missouri.[186] Holding the Chicago Daily Tribune he posed for reporters to capture the moment. Time magazine later called it the "greatest photograph ever made of a politician celebrating victory".[2] Author and Truman's biographer David McCullough later wrote:

Like some other photographs of other presidents – of Theodore Roosevelt in a white linen suit at the controls of a steam shovel in Panama, or Woodrow Wilson at Versailles, or Franklin Roosevelt, chin up, singing an old hymn beside Winston Churchill on board the Prince of Wales in the dark summer of 1941 – this of Harry Truman in 1948 would convey the spirit of both the man and the moment as almost nothing else would.[187]

Results

[edit]| Presidential candidate | Party | Home state | Popular vote | Electoral vote |

Running mate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | Percentage | Vice-presidential candidate | Home state | Electoral vote | ||||

| Harry S. Truman (Incumbent) | Democratic | Missouri | 24,179,347 | 49.55% | 303 | Alben W. Barkley | Kentucky | 303 |

| Thomas E. Dewey | Republican | New York | 21,991,292 | 45.07% | 189 | Earl Warren | California | 189 |

| Strom Thurmond | States' Rights Democratic | South Carolina | 1,175,930 | 2.41% | 39 | Fielding L. Wright | Mississippi | 39 |

| Henry A. Wallace | Progressive/American Labor | New York | 1,157,328 | 2.37% | 0 | Glen H. Taylor | Idaho | 0 |

| Norman Thomas | Socialist | New York | 139,569 | 0.29% | 0 | Tucker Powell Smith | Michigan | 0 |

| Claude A. Watson | Prohibition | California | 103,708 | 0.21% | 0 | Dale Learn | Pennsylvania | 0 |

| Edward A. Teichert | Socialist Labor | Pennsylvania | 29,244 | 0.06% | 0 | Stephen Emery | New York | 0 |

| Farrell Dobbs | Socialist Workers | Minnesota | 13,613 | 0.03% | 0 | Grace Carlson | Minnesota | 0 |

| Other | 3,504 | 0.01% | — | Other | — | |||

| Total | 48,793,535 | 100% | 531 | 531 | ||||

| Needed to win | 266 | 266 | ||||||

Source

- Electoral Vote: "1948 Electoral College Results". National Archives and Records Administration. November 5, 2019. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- Popular Vote: Leip, Dave. "1948 Presidential General Election Results". Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

Aftermath and legacy

[edit]

President Truman and Vice President-elect Barkley were inaugurated on January 20, 1949 – the first nationally televised inauguration.[188] In his second term as president, Congress ratified the 22nd Amendment, making a president ineligible for election to a third term or for election to a second full term after serving more than two remaining years of a term of a previously elected president.[189] As Truman was eligible to run in 1952, he contested the New Hampshire primaries, but lost to Senator Estes Kefauver.[190] During the Korean War, his approval rating had dropped to approximately twenty percent. A few days after the New Hampshire primary, Truman formally announced he would not seek a second full term.[191] Truman was eventually able to persuade Adlai Stevenson to run, and the governor gained the nomination at the 1952 Democratic National Convention.[192] Stevenson lost the 1952 presidential election to the Republican nominee – Dwight D. Eisenhower – in a landslide.[193]

Truman's 1948 campaign and the election are most remembered for the failure of polls, which predicted an easy win for Governor Dewey.[194] One reason for the press's inaccurate projection was that polls were conducted primarily by telephone, but many people, including much of Truman's populist base, did not own a telephone. The Gallup Poll had assumed that the final stages of the campaign would have no significant impact on the result.[195] However, post-election surveys concluded that one of every seven voters had made up their mind within the last fortnight of the campaign.[196] The Social Science Research Council report stated: "the error in predicting the actual vote from expressed intention to vote was undoubtedly an important, although not precisely measurable, part of the over-all error of the forecast."[197]

Truman single-handedly coordinated his campaign, making a direct appeal to farmers, who traditionally voted for the Republican Party.[198] Leverett Saltonstall, a Republican senator from Massachusetts, argued that overconfidence had led the Republicans to "put on a campaign of generalities rather than interesting the people in what a Republican administration could and would do for them if elected".[199] The Rowe–Clifford memo was later described by The Washington Post as "one of this century's most famous political memorandums".[28] Author Irvin Ross argued that Truman's success in holding together the Roosevelt coalition helped him organize a successful campaign.[200] McCullough noted that when it came to his message, Truman had just one strategy: "attack, attack, attack, carry the fight to the enemy's camp".[109] Years later, President Lyndon B. Johnson, who was first elected to the senate in the 1948 election, said:

The American people love Harry Truman, not because he gave them hell, but because he gave them hope.[201]

See also

[edit]Notes and references

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ July 26 is referred to as Turnip Day in Missouri, as the turnip crop is traditionally sown on that day. Truman himself was a farmer for eleven years prior becoming a politician.[83]

- ^ The number of campaign stops (238 for Truman and 40 for Dewey) are from September 2 till the election day. It differs from the number of days spent in the state, or his overall number of tours.[138]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Murphy 2003, p. 259.

- ^ a b c Baime 2020, p. 342.

- ^ McCullough 1992, pp. 36–37.

- ^ Ferrell 2013, pp. 25–26.

- ^ Offner 2002, p. 6.

- ^ McCullough 1992, p. 115.

- ^ Baime 2020, p. 30.

- ^ Riddle 1964, pp. 16–17.

- ^ Baime 2020, p. 32.

- ^ McCullough 1992, pp. 294–295.

- ^ McCullough 1992, pp. 305–307.

- ^ Busch 2012, pp. 98–100.

- ^ McCullough 1992, pp. 345–347.

- ^ Parks 1991, p. 23.

- ^ McCullough 1992, p. 348.

- ^ McCullough 1992, pp. 459–464.

- ^ Dallek 2008, pp. 24–28.

- ^ Baime 2020, p. 5.

- ^ Baime 2020, p. x.

- ^ Karabell 2001, p. 34.

- ^ a b McCullough 1992, p. 584.

- ^ Yarnell 1974, pp. 2–4.

- ^ Ross 1968, p. 69.

- ^ a b McCullough 1992, pp. 584–586.

- ^ a b c d Busch 2012, p. 104.

- ^ Busch 2012, p. 79.

- ^ Lemelin 2001, pp. 39–40.

- ^ a b c d Baime 2020, p. 95.

- ^ Sitkoff 1971, p. 597.

- ^ a b c Baime 2020, p. 96.

- ^ a b Lemelin 2001, p. 6.

- ^ Gardner 2002, p. 65.

- ^ Ross 1968, p. 70.

- ^ Karabell 2001, p. 59.

- ^ a b SAGE Publications 2009, pp. 397–398.

- ^ McCullough 1992, p. 608.

- ^ Busch 2012, p. 2.

- ^ Busch 2012, p. 80.

- ^ Baime 2020, p. 124.

- ^ Bray 1964, p. 1.

- ^ Goldzwig 2008, p. 21.

- ^ Busch 2012, p. 206.

- ^ McCullough 1992, p. 624.

- ^ Karabell 2001, p. 131.

- ^ Ross 1968, p. 83.

- ^ McCullough 1992, p. 625.

- ^ Karabell 2001, pp. 131–133.

- ^ Goldzwig 2008, p. 24.

- ^ McCullough 1992, p. 628.

- ^ a b Baime 2020, p. 127.

- ^ McCullough 1992, p. 635.

- ^ Baime 2020, p. 144.

- ^ Baime 2020, p. 142.

- ^ a b Baime 2020, p. 143.

- ^ Donovan 1977, p. 404.

- ^ The New York Times 1948, p. 19.

- ^ Logansport Pharos-Tribune 1948, p. 1.

- ^ McCullough 1992, p. 636.

- ^ Donaldson 1999, p. 160.

- ^ McCullough 1992, p. 637.

- ^ Karabell 2001, p. 156.

- ^ a b c d McCullough 1992, p. 638.

- ^ Karabell 2001, pp. 156–157.

- ^ McCullough 1992, pp. 638–639.

- ^ a b c Baime 2020, p. 147.

- ^ a b Karabell 2001, pp. 157–158.

- ^ Busch 2012, pp. 104–108.

- ^ Busch 2012, pp. 106–107.

- ^ Murphy 2020, p. 77.

- ^ Busch 2012, p. 107.

- ^ Baime 2020, p. 148.

- ^ Busch 2012, p. 108.

- ^ a b Karabell 2001, p. 159.

- ^ Donaldson 1999, p. 164.

- ^ Gullan 1998, p. 101.

- ^ McCullough 1992, p. 641.

- ^ McCullough 1992, pp. 641–643.

- ^ Pietrusza 2014, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Truman 2003, p. 53.

- ^ Brown 1948, pp. 300–301.

- ^ Lee 1963, p. 256.

- ^ a b Pietrusza 2014, p. 4.

- ^ Batt & Balducchi 1999, p. 82.

- ^ a b Truman 2003, p. 59.

- ^ a b Pietrusza 2014, p. 1.

- ^ McCullough 1992, p. 653.

- ^ a b Truman 2003, p. 4.

- ^ McCullough 1992, p. 644.

- ^ Gullan 1998, pp. 104–105.

- ^ Savage 1997, p. 122.

- ^ Baime 2020, pp. 174–176.

- ^ Baime 2020, p. 186.

- ^ Baime 2020, p. 175.

- ^ Baime 2020, p. 176.

- ^ Baime 2020, p. 177.

- ^ Gullan 1998, pp. 106–107.

- ^ a b Baime 2020, pp. 178–181.

- ^ Baime 2020, p. 179.

- ^ McCullough 1992, p. 651.

- ^ Gullan 1998, pp. 108–109.

- ^ Donaldson 1999, p. 168.

- ^ Karabell 2001, pp. 188–189.

- ^ Donovan 1977, p. 413.

- ^ Jasen 2002, p. 98.

- ^ Matviko 2005, p. 41.

- ^ Baime 2020, p. 200.

- ^ McCullough 1992, p. 652.

- ^ Karabell 2001, p. 191.

- ^ a b Busch 2012, p. 128.

- ^ a b Baime 2020, p. 214.

- ^ McCullough 1992, p. 657.

- ^ Baime 2020, p. 269.

- ^ a b McCullough 1992, p. 656.

- ^ Truman Library (b), p. 3.

- ^ Murphy 1948, p. 2.

- ^ a b McCullough 1992, p. 654.

- ^ Karabell 2001, p. 210.

- ^ Karabell 2001, p. 211.

- ^ Karabell 2001, p. 206.

- ^ Karabell 2001, p. 202.

- ^ a b Truman 2003, p. 85.

- ^ Goldzwig 2008, p. 18.

- ^ Truman Library (a), pp. 1–6.

- ^ Goldzwig 2008, p. 52.

- ^ McCullough 1992, p. 661.

- ^ a b McCullough 1992, p. 663.

- ^ a b Baime 2020, p. 248.

- ^ McCullough 1992, p. 664.

- ^ Karabell 2001, p. 217.

- ^ McCullough 1992, pp. 679–680.

- ^ McCullough 1992, p. 680.

- ^ White 2014, p. 184.

- ^ McCullough 1992, pp. 688–689.

- ^ Truman 2003, p. 115.

- ^ White 2014, p. 203.

- ^ White 2014, p. 10.

- ^ Karabell 2001, p. 212.

- ^ Holbrook 2002, p. 61.

- ^ Holbrook 2002, p. 60.

- ^ a b Baime 2020, p. 296.

- ^ Visser 1994, p. 48.

- ^ Rosenof 1999, p. 63.

- ^ Ross 1968, p. 166.

- ^ a b Lemelin 2001, p. 42.

- ^ Frantz 1995, p. 86.

- ^ a b McCullough 1992, p. 694.

- ^ Karabell 2001, p. 218.

- ^ Ferrell 2013, p. 20.

- ^ Karabell 2001, p. 228.

- ^ Karabell 2001, p. 213.

- ^ Karabell 2001, p. 242.

- ^ a b McCullough 1992, pp. 697–698.

- ^ a b Baime 2020, pp. 264–278.

- ^ McCullough 1992, pp. 685–687.

- ^ McCullough 1992, pp. 687–689.

- ^ a b McCullough 1992, p. 687.

- ^ a b Bogardus 1949, p. 80.

- ^ Donaldson 1999, pp. 182–183.

- ^ Baime 2020, p. 274.

- ^ Karabell 2001, p. 243.

- ^ Donaldson 1999, p. 183.

- ^ McCullough 1992, p. 699.

- ^ McCullough 1992, p. 696.

- ^ Baime 2020, p. v.

- ^ McCullough 1992, pp. 697–702.

- ^ Karabell 2001, p. 245.

- ^ a b McCullough 1992, pp. 700–701.

- ^ McCullough 1992, pp. 701–703.

- ^ Baime 2020, p. 185.

- ^ Baime 2020, p. 297.

- ^ McCullough 1992, p. 705.

- ^ McCullough 1992, pp. 705–706.

- ^ McCullough 1992, p. 706.

- ^ Bray 1964, p. 38.

- ^ McCullough 1992, p. 707.

- ^ McCullough 1992, pp. 706–708.

- ^ McCullough 1992, p. 709.

- ^ Karabell 2001, p. 7.

- ^ Savage 1997, p. 138.

- ^ Brown 1948, pp. 558–562.

- ^ Gullan 1998, p. 176.

- ^ McCullough 1992, p. 711.

- ^ McCullough 1992, pp. 709–710.

- ^ Sitkoff 1971, p. 613.

- ^ McCullough 1992, p. 708.

- ^ McCullough 1992, pp. 718–719.

- ^ McCullough 1992, p. 718.

- ^ McCullough 1992, p. 723.

- ^ SAGE Publications 2009, p. 19.

- ^ SAGE Publications 2009, p. 399.

- ^ Busch 2012, p. 189.

- ^ Busch 2012, p. 183.

- ^ The New York Times 1952, p. 26.

- ^ McDonald et al. 2001, pp. 141–142.

- ^ Ross 1968, p. 250.

- ^ Ross 1968, pp. 250–251.

- ^ Ross 1968, pp. 251–252.

- ^ Bogardus 1949, pp. 81–83.

- ^ Ross 1968, p. 260.

- ^ Ross 1968, p. 263.

- ^ Truman 2003, p. 224.

Works cited

[edit]Books

[edit]- Baime, A. J. (2020). Dewey Defeats Truman – The 1948 Election and the Battle for America's Soul. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-1-328-58506-6. OL 29821320M.

- Brown, C. Edgar, ed. (1948). Democracy At Work – Being The Official Report of The Democratic National Convention. Democratic Political Committee of Pennsylvania. OL 32092434M. Retrieved November 8, 2021 – via the Internet Archive.

- Busch, Andrew E. (2012). Truman's Triumphs – The 1948 Election and the Making of Postwar America. University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-1866-8. LCCN 2012020593. OL 26379614M. Retrieved November 8, 2021 – via the Internet Archive.

- Dallek, Robert (2008). Harry S. Truman. Times Books. ISBN 978-0-8050-6938-9. LCCN 2008010193. OL 18500662M. Retrieved November 14, 2021 – via the Internet Archive.

- Donaldson, Gary (1999). Truman Defeats Dewey. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-2075-1. LCCN 98024424. OL 364156M. Retrieved November 8, 2021 – via the Internet Archive.

- Donovan, Robert J. (1977). Conflict and Crisis – The Presidency of Harry S. Truman, 1945–1948. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-05636-5. LCCN 77009584. OL 21351731M. Retrieved November 8, 2021 – via the Internet Archive.

- Ferrell, Robert H. (2013). Harry S. Truman – A Life. University of Missouri Press. ISBN 978-0-8262-6045-1. Retrieved November 8, 2021 – via the Internet Archive.

- Frantz, Douglas (1995). Friends in High Places – The Rise and Fall of Clark Clifford. Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 978-0-316-29162-0. LCCN 95002361. OL 1271143M. Retrieved November 8, 2021 – via the Internet Archive.

- Gardner, Michael R. (2002). Harry Truman and Civil Rights. Southern Illinois University Press. ISBN 978-0-8093-2425-5. LCCN 2001041154. OL 3949738M. Retrieved November 8, 2021 – via the Internet Archive.

- Goldzwig, Steven R. (2008). Truman's Whistle-Stop Campaign. Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 978-1-60344-398-2. OL 26148568M. Retrieved November 8, 2021 – via the Internet Archive.

- Gullan, Harold I. (1998). The Upset That Wasn't – Harry S Truman and the Crucial Election of 1948. Ivan R. Dee Publisher. ISBN 978-1-56663-206-5. LCCN 98026167. OL 365819M. Retrieved November 8, 2021 – via the Internet Archive.

- Jasen, David A. (2002). A Century of American Popular Music – 2000 Best-loved and Remembered Songs (1899–1999). Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-93700-9. Retrieved November 8, 2021 – via the Internet Archive.

- Karabell, Zachary (2001). The Last Campaign – How Harry Truman Won the 1948 Election. Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-307-42886-8. OL 7426117M. Retrieved November 8, 2021 – via the Internet Archive.

- Matviko, John W., ed. (2005). The American President in Popular Culture. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-32705-6. LCCN 2005006570. OL 17174066M. Retrieved November 8, 2021 – via the Internet Archive.

- McCullough, David (1992). Truman. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-86920-5. LCCN 92005245. OL 1704072M. Retrieved November 8, 2021 – via the Internet Archive.

- Murphy, Bruce Allen (2003). Wild Bill – The Legend and Life of William O. Douglas. Random House. ISBN 978-0-394-57628-2. LCCN 2002023114. OL 3559985M. Retrieved November 8, 2021 – via the Internet Archive.

- Offner, Arnold A. (2002). Another Such Victory – President Truman and the Cold War, 1945–1953. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-4254-2. OL 7929507M. Retrieved November 8, 2021 – via the Internet Archive.

- Parks, Arva Moore (1991). Harry Truman and the Little White House in Key West. Centennial Press. ISBN 978-0-9629402-0-0. LCCN 93144349. OL 1478363M. Retrieved November 8, 2021 – via the Internet Archive.

- Riddle, Donald H. (1964). The Truman Committee – A Study in Congressional Responsibility. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-608-30714-5. LCCN 63016306. OL 5884350M. Retrieved November 8, 2021 – via the Internet Archive.

- Ross, Irwin (1968). The Loneliest Campaign – The Truman Victory of 1948. New American Library. ISBN 978-0-8371-8353-4. LCCN 68018257. OL 19806779M. Retrieved November 8, 2021 – via the Internet Archive.

- Savage, Sean J. (1997). Truman and the Democratic Party. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-2003-4. LCCN 96049954. OL 28536604M. Retrieved November 8, 2021 – via the Internet Archive.

- Truman, Harry S. (2003). Neal, Steve (ed.). Miracle of '48 – Harry Truman's Major Campaign Speeches & Selected Whistle-Stops. Southern Illinois University Press. ISBN 978-0-8093-2557-3. LCCN 2003010658. OL 3675149M. Retrieved November 8, 2021 – via the Internet Archive.

- White, Philip (2014). Whistle Stop – How 31,000 miles of Train Travel, 352 Speeches, and a Little Midwest Gumption Saved the Presidency of Harry Truman. University Press of New England. ISBN 978-1-322-24235-4. OL 28301464M. Retrieved November 8, 2021 – via the Internet Archive.

- Yarnell, Allen (1974). Democrats and Progressives – The 1948 Presidential Election as a Test of Postwar Liberalism. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-02539-4. LCCN 73083060. OL 26361502M. Retrieved November 8, 2021 – via the Internet Archive.

- Guide to U.S. Elections (6th ed.). SAGE Publications. 2009. ISBN 978-1-60426-536-1. LCCN 2009033938.

Journals and articles

[edit]- Batt, William L.; Balducchi, David E. (1999). "Origin of the 1948 Turnip Day Session of Congress". Presidential Studies Quarterly. 29 (1). Wiley: 80–83. doi:10.1111/1741-5705.00020. ISSN 0360-4918. JSTOR 27551960.

- Bogardus, Emory S. (1949). "Public Opinion and the Presidential Election of 1948". Social Forces. 28 (1). Oxford University Press: 79–83. doi:10.2307/2572103. ISSN 0037-7732. JSTOR 2572103.

- Bray, William J. (1964). "Recollections of the 1948 Campaign". Harry S. Truman Library and Museum. Political File. Archived from the original on July 4, 2021. Retrieved June 29, 2021.

- Holbrook, Thomas M. (2002). "Did the Whistle-Stop Campaign Matter?". PS: Political Science & Politics. 35 (1). American Political Science Association: 59–66. doi:10.1017/S104909650200015X. ISSN 1049-0965. JSTOR 1554764. S2CID 154881179.

- Knowles, Clayton (July 7, 1948). "Eisenhower Stand Buoys Truman Men". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on December 30, 2018. Retrieved October 16, 2021.

- Lee, R. Alton (1963). "The Turnip Session of the Do-Nothing Congress – Presidential Campaign Strategy". The Southwestern Social Science Quarterly. 44 (3): 256–267. ISSN 0038-4941. JSTOR 42867014.

- Lemelin, Bernard (2001). "The U.S. Presidential Election of 1948 – The Causes of Truman's 'Astonishing' Victory". Revue française d'études américaines. 87: 38–61. doi:10.3917/rfea.087.0038. ISSN 0397-7870.

- McDonald, Daniel G.; Glynn, Carroll J.; Kim, Sei-Hill; Ostman, Ronald E. (April 2001). "The Spiral of Silence in the 1948 Presidential Election". Communication Research. 28 (2): 139–155. doi:10.1177/009365001028002001. ISSN 0093-6502. S2CID 13165150.

- Murphy, Charles S. (December 6, 1948). "Some Aspects of the Preparation of President Truman's Speeches for the 1948 Campaign". Harry S. Truman Library and Museum. Truman Administration File. Archived from the original on July 4, 2021. Retrieved June 29, 2021.

- Murphy, John M. (2020). "The Sunshine of Human Rights – Hubert Humphrey at the 1948 Democratic Convention". Rhetoric and Public Affairs. 23 (1): 77–106. doi:10.14321/rhetpublaffa.23.1.0077. ISSN 1094-8392. JSTOR 10.14321/rhetpublaffa.23.1.0077. S2CID 216286175.

- Pietrusza, David (2014). "Harry S. Truman's Speech at the 1948 Democratic National Convention – Harry S. Truman (July 15, 1948)" (PDF). Library of Congress. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 22, 2021. Retrieved June 23, 2021.

- Rosenof, Theodore (1999). "The Legend of Louis Bean: Political Prophecy and the 1948 Election". The Historian. 62 (1): 63–78. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6563.1999.tb01434.x. ISSN 0018-2370. JSTOR 24450539.

- Sitkoff, Harvard (1971). "Harry Truman and the Election of 1948: The Coming of Age of Civil Rights in American Politics". The Journal of Southern History. 37 (4): 597–616. doi:10.2307/2206548. ISSN 0022-4642. JSTOR 2206548.

- Visser, Max (1994). "The Psychology of Voting Action: On the Psychological Origins of Electoral Research, 1939-1964". Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences. 30: 43–52. doi:10.1002/1520-6696(199401)30:1<43::AID-JHBS2300300105>3.0.CO;2-D. hdl:2066/213365. ISSN 0022-5061.

- "List of Campaign Speeches". Truman Administration File. Harry S. Truman Library and Museum. Archived from the original on July 4, 2021. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- "List to board President's special train, Toledo, Ohio". President's Secretary's Files. Harry S. Truman Library and Museum. Archived from the original on July 4, 2021. Retrieved June 29, 2021.

- "Persist In Movement To Draft Eisenhower". Logansport Pharos-Tribune. July 7, 1948. Archived from the original on December 2, 2021. Retrieved December 2, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Eisenhower Wins". The New York Times. November 5, 1952. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on November 13, 2021. Retrieved November 13, 2021.

Further reading

[edit]- Dean, Virgil W. (1993). "Farm Policy and Truman's 1948 Campaign". The Historian. 55 (3): 501–516. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6563.1993.tb00908.x. ISSN 0018-2370. JSTOR 24448612.

- Miscamble, Wilson D. (1980). "Harry S. Truman, the Berlin Blockade and the 1948 Election". Presidential Studies Quarterly. 10 (3). Center for the Study of the Presidency and Congress: 306–316. ISSN 0360-4918. JSTOR 27547587.

External links

[edit] Media related to Harry S. Truman 1948 presidential campaign at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Harry S. Truman 1948 presidential campaign at Wikimedia Commons- President Harry Truman 1948 Presidential Acceptance Speech – (C-SPAN)

- 1948 election campaign collection – (Harry S. Truman Presidential Library and Museum)

- The Truman Story – (British-Pathe)

- The Dewey Story – (C-SPAN)

- President Truman Inauguration speech – (C-SPAN)

- Harry S. Truman's post-presidential interviews – (Attr. – Screen Gems Collection, Harry S. Truman Presidential Library and Museum (in Public Domain); National Archives Catalog record)