History of Portland, Maine

| History of Maine |

|---|

|

| Periods |

| Topics |

| Places |

|

|

The History of Portland, Maine, begins when Native Americans originally called the Portland peninsula Məkíhkanək meaning "At the fish hook" in Penobscot[1][2] and Machigonne (meaning "Great Neck")[3] in Algonquian. The peninsula and surrounding areas were home to members of the Algonquian-speaking Aucocisco branch of the Eastern Abenaki tribe, who died largely due to the introduction of foreign illnesses during colonization. Some were forcibly relocated to current day New Hampshire and Canada during European settlement.[4]

Native Americans

[edit]There is evidence of Native American presence in what is now called Maine as early as 11,000 BCE. At the time of European contact in the sixteenth century, Algonquian speaking people inhabited present-day Portland. French explorer Samuel de Champlain identified these people as the "Almouchiquois," a polity stretching from the Androscoggin River to Cape Ann and culturally distinct from their Wampanoag and Abenaki neighbors. According to Captain John Smith in 1614, a semi-autonomous band called the “Aucocisco” inhabited "the bottome of a large deepe Bay, full of many great Iles." This bay would later come to be known as Casco Bay, and include the future site of Portland.[5]

A combination of warfare and disease decimated Native peoples in the years preceding English colonization, creating a "shatter zone" of devastation and political instability in what would become southern Maine. The introduction of European goods in the 1500s disrupted long-standing Native trade relationships in the northeast. Starting around 1607, Micmacs began raiding their southern neighbors from the Gulf of Maine to Massachusetts in an effort to corner the lucrative fur trade and monopolize access to European goods. The arrival of foreign pathogens only served to compound the violence in the region. A particularly notorious pandemic between 1614 and 1620 ravaged the population of coastal New England with mortality rates at upwards of 90 percent. In this chaotic milieu, groups like the Almouchiquois disappear from the historical record, as they were likely displaced or incorporated into other tribes. However, larger Native communities maintained a presence in the Casco Bay area until King George's War in the 1740s. French military defeat and increasing English settler migration to the area from primarily southern New England impelled most Native Americans to migrate toward the protection of New France, or further up the coast where they remain today.[6]

European settlement

[edit]

The first European to attempt settlement was Christopher Levett, an English naval captain who was granted 6,000 acres (24 km2) from the King of England in 1623 to found a permanent settlement in Casco Bay. Levett proposed naming it York after York, England, the town of his birth. Levett was a member of the Plymouth Council for New England and an agent for Sir Ferdinando Gorges, Lord Proprietor of Maine. Levett sailed from England to arrive on the Isles of Shoals in October, 1623. He then spent a month with David Thompson at Piscataqua where he assembled men who had arrived earlier to survey the Gulf of Maine for a suitable site to build a trading house. Levett left some of these men at Casco when he returned to England in midsummer 1624.[7] He wrote a book about his voyage, hoping to generate support for the settlement.[8] But his efforts yielded little interest, and Levett never returned to Maine. He did sail to Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1630 to confer with Governor John Winthrop, but died during return passage to England. It's unknown what became of the men he left behind at Machigonne. Fort Levett, built in 1894 on Cushing Island in Portland Harbor, is named for him.[9][10]

The next (and first permanent) settlement came in 1633 when George Cleeve and Richard Tucker established a fishing and trading village. The town was then renamed Casco. In 1658, the Massachusetts Bay Colony took control of the area, changing its name again, this time to Falmouth after Falmouth, England, the site of an important Parliamentary victory in the English Civil War. An obelisk monument at the end of Congress Street, where it meets the Eastern Promenade, commemorates the four historical names of Portland. [11][12]

Raid on Portland (1676)

[edit]In 1676, the village was completely destroyed by the Abenaki people during King Philip's War. When English colonists returned in 1678, they erected Fort Loyal on India Street to ward off future attacks.

Battle of Falmouth (1690)

[edit]

The village was again destroyed in 1690 during King William's War by a combined force of 400-500 French and Indians in the Battle of Falmouth. Portland's peninsula was deserted for more than ten years after the attack. Massachusetts built another fort to the north of the Presumpscot River in present-day Falmouth called Fort New Casco in 1698. Fort New Casco was successfully defended during the Northeast Coast Campaign (1703) of Queen Anne's War. Fort Loyal at the base of India Street was used throughout King George's War and then repaired during the French and Indian War in 1755.[13]

American Revolution

[edit]On October 18, 1775, the community was destroyed yet again, bombarded for 9 hours during the Revolutionary War by the Royal Navy's HMS Canceaux under command of Lieutenant Henry Mowat.[14] The Burning of Falmouth left three-quarters of the town in ashes -- and its citizens committed to independence. When rebuilt, the community's center shifted from India Street to where the Old Port district is today. [15][16]

Trade and shipping center

[edit]

Following the war, a section of Falmouth called The Neck developed as a commercial port and began to grow rapidly as a shipping center. In 1786, the citizens of Falmouth formed a separate town in Falmouth Neck and named it Portland. Portland's economy was greatly stressed by the Embargo Act of 1807 (prohibition of trade with the British), which ended in 1809, and the War of 1812, which ended in 1815. In 1820, Maine became a state and Portland was selected as its capital. Reuben Ruby and other free African Americans founded the Abyssinian Meeting House in 1828 on Newbury Street in the East End. In 1832, the capital was moved to Augusta. [17]

In 1851, Maine led the nation by passing the first state law to prohibit the sale of alcohol except for "medicinal, mechanical or manufacturing purposes." The law subsequently became known as the Maine law as 18 states quickly followed Maine. Portland was a center for protests against the law, and the protests culminated on June 2, 1855 in the Portland Rum Riot. Between 1,000 and 3,000 people opposed to the law gathered because Neal S. Dow, the mayor of Portland and a Maine Temperance Society leader, had authorized a shipment of $1,600 of "medicinal and mechanical alcohol." The protesters believed, falsely, that this shipment was for private use. When the protesters failed to disperse, Dow ordered the militia to fire. One man was killed and seven were wounded. Following the outcome of the Portland Rum Riot, the Maine law was repealed in 1856. [18]

The Cumberland and Oxford Canal extended waterborne commerce from Portland harbor to Sebago Lake and Long Lake in 1832. Portland became the primary ice-free winter seaport for Canadian exports upon completion of the Grand Trunk Railway to Montreal in 1853. The city's major passenger rail terminal, Union Station, was opened in 1888. In the 19th century, The Portland Company manufactured more than 600 steam locomotives. Portland became a 20th-century rail hub as five additional rail lines merged into Portland Terminal Company in 1911. Canadian export traffic was diverted from Portland to Halifax, Nova Scotia following nationalization of the Grand Trunk system in 1923; and 20th-century icebreakers later enabled ships to reach Montreal throughout the winter. [19]

In 1880, the Portland Longshoremans Benevolent Society was formed. A primarily Irish and Irish-American trade union, it organized between 400 and nearly 1,400 dockworkers for higher wages and went on short strikes in 1911 and 1913. Membership peaked in 1919 as a result of World War I and Europe's need for Canadian grain.

Regional cosmopolitan capital

[edit]

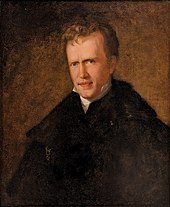

Portland's period of greatest cosmopolitan prominence was in the first four decades of the nineteenth century, when the city was "a rival, and not a satellite of either Boston or New York."[20] In that period, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow got his start as a young poet and John Neal held a central position in leading American literature toward its great renaissance,[21][22] having founded Maine's first literary periodical, The Yankee, in 1828.[23] Other notable literary or artistic figures who got their start or were at their prime in that period include Grenville Mellen, Nathaniel Parker Willis, Seba Smith, Elizabeth Oakes Smith, Benjamin Paul Akers, Charles Codman, Franklin Simmons, John Rollin Tilton, and Harrison Bird Brown.

The Great Fire and rebuilding

[edit]

The Great Fire of July 4, 1866, ignited during the Independence Day celebration, destroyed most of the commercial buildings in the city, half the churches and hundreds of homes. More than 10,000 people were left homeless. After this fire, Portland was rebuilt with brick and took on a Victorian appearance. Prosperous citizens began building mansions in the city's fashionable West End. [24]

The quality and style of architecture in Portland is in large part due to the succession of well-known 19th-century architects who worked in the city. Alexander Parris (1780–1852) arrived about 1800 and endowed Portland with numerous Federal style buildings, although some were lost in the 1866 fire. Charles A. Alexander (1822–1882) designed numerous Victorian mansions. Henry Rowe (1810–1870) specialized in Gothic cottages. George M. Harding (1827–1910) designed many of the commercial buildings in the Old Port of Portland, Maine, as well as ornate residential buildings. Around the turn of the century, Frederick A. Tompson (1857–1919) also designed many of city's residential buildings. [25]

But by far the most influential and prolific architects of the West End area were Francis H. Fassett (1823–1908) and John Calvin Stevens (1855–1940). Fassett was commissioned to build the Maine General Hospital Building (now a wing of the Maine Medical Center) and the Williston West Church as well as many other churches, schools, commercial buildings, apartment buildings, private residences, and his own duplex home on Pine Street. From the early 1880s to the 1930s Stevens worked in a wide range of styles from the Queen Anne and Romanesque popular at the beginning of his career, to the Mission Revival Style of the 1920s, but the architect is best known for his pioneering efforts in the Shingle and Colonial Revival styles, examples of which abound in this area.

In 1895–1896, electric streetcars replaced horse-drawn carriages as the primary method of transportation into and around Portland. A week-long strike disrupted transportion beginning on July 12, 1916 and lasted until July 17. The laborers, with widespread community support, won union recognition and other improvements.[26]

Second World War

[edit]Casco Bay became destroyer base Sail when the United States Navy began escorting HX, SC, and ON convoys of the Battle of the Atlantic. Destroyer tender USS Denebola (AD-12) provided repair services at Portland from 12 September 1941 until 5 July 1944.[27] Convoy escorts as large as battleships used the large protected anchorage adjacent to good railway facilities for delivery of supplies. Sailors on shore leave enjoyed Portland's recreational opportunities, and the waters offshore were suitable for gunnery practice. Construction of facilities began in the summer of 1941,[28] and ultimately included a Fleet Post Office, Naval Dispensary, Navy routing office, Navy Relief Society office, registered publications issuing office, Port Director, Portland harbor entrance control post, Maritime Commission depot, and headquarters for the Portland sections of the naval local defense force and inshore patrol. There was a Navy recruiting station, an armed forces induction station, and a naval training center. Radio direction finder and LORAN training was at the fleet signal station; and the naval receiving station included schools for destroyer communications officers and signalman, radioman, and quartermaster strikers. Unused piers adjacent to the Grand Trunk Railway yard were converted to training facilities for combat information center (CIC), night visual lookouts, surface and aircraft recognition, search and fire control radar operators, gunnery spotting, anti-aircraft machine guns, and anti-submarine warfare (ASW) attack. Little Chebeague Island was used for a fire fighters school; and torpedo control officers were trained near the navy supply pier, naval fuel annex, and Casco Bay Naval Auxiliary Air Facility (NAAF) seaplane base built on Long Island.[29]

Decline and revival

[edit]

The erection of the Maine Mall, an indoor shopping center established in the suburb of South Portland during the 1970s, had a significant effect on Portland's downtown. Department stores and other major franchises, many from Congress Street or Free Street, either moved to the nearby mall or went out of business. This was a mixed blessing for locals, protecting the city's character (chain stores are often uninterested in it now) but led to a number of empty storefronts. Residents had to venture out of town for certain products and services no longer available on the peninsula.[citation needed]

But now the old seaport is attracting residents and investment. Because of the city government's emphasis on preservation, much of the opulent Victorian architecture of Portland's rebuilding has been restored. In 1982, the area was entered on the National Register of Historic Places. In modern lifestyle surveys, it is often cited as one of America's best small cities to live in.

Portland is currently experiencing a building boom. In recent years, Congress Street has become home to more stores and eateries, spurred on by the expanding Maine College of Art and the conversion of office buildings to high-end condos. Rapid development is occurring in the historically industrial Bayside neighborhood, as well as the emerging harborside Ocean Gateway neighborhood at the base of Munjoy Hill.[30][31][32]

On November 1, 2014, a fire killed 6 people on Noyes Street near the University of Southern Maine campus.

Street namesakes

[edit]In 1995, a two-year study was completed, during which it was discovered that fifty of the city's 850 streets were named for particular subjects.[33] Allen Avenue is named for landowner Solomon Allen. Bramhall Street is named for George Bramhall, who owned a large tannery near the Western Promenade. Clark Street, meanwhile, is named for early settler Thaddeus Clark.[34]

Old postcards of Portland

[edit]-

Northeast from City Hall c. 1910

-

Monument Square c. 1908

-

State Street c. 1906

-

Western Promenade c. 1908

West End architecture

[edit]-

A house on Chadwick Street

-

A view down Carroll Street

-

A Vaughan Street residence

-

The West Mansion on the Western Promenade

See also

[edit]- Timeline of Portland, Maine, history

- Fort Gorges

- Fort Scammel

- Maine Historical Society & Museum

- McLellan-Sweat Mansion

- Munjoy Hill

- Portland City Hall

- Portland Museum of Art

- Portland Observatory

- Railroad history of Portland, Maine

- St. Lawrence and Atlantic Railroad

- Wadsworth-Longfellow House

- Victoria Mansion

- Portland Freedom Trail

- Abyssinian Meeting House

References

[edit]- ^ "Penobscot Dictionary entry". Penobscot Dictionary. the Penobscot Indian Nation, the University of Maine, and the American Philosophical Society. Retrieved 29 November 2023.

- ^ "Penobscot Dictionary Project". University Of Maine Library System. Retrieved 29 November 2023.

- ^ History of Portland, Maine, Maine Resource Guide, archived from the original on January 31, 2013

- ^ "The Almouchiquois". Falmouth Historical Society. Retrieved 29 November 2023.

- ^ Bruce J. Borque, Twelve Thousand Years: American Indians in Maine (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2002), 16; Emerson W. Baker, “Finding the Almouchiquois: Native American Families, Territories, and Land Sales in Southern Maine,” Ethnohistory 51, no. 1 (Winter 2004): 73-100; John Smith, A Description of New England (1616): An Online Electronic Text Edition, Paul Royster, ed., 36.

- ^ Christopher Levett, A Voyage into New England: Begun in 1623, and Ended in 1624 (London, 1628); Neal Salisbury, °Manitou and Providence: Indians, Europeans, and the Making of New England, 1500-1643 (New York, Oxford University Press, 1982), 50-84; David L. Ghere, "The 'Disappearance of the Abenaki in Western Maine: Political Organization and Ethnocentric Assumptions," American Indian Quarterly 17, no. 2 (Spring 1993): 193-207.

- ^ Anderson, Robert Charles (2024). "1623". American Ancestors. 25 (3). American Ancestors: 40–45.

- ^ Christopher Levett, of York: The Pioneer Colonist in Casco Bay, James Baxter Phinney,1893

- ^ The Maine Reader: The Down East Experience from 1614 to the Present, Charles E. Shain, 1997

- ^ Christopher Levett: The First Owner of the Soil of Portland, Collections of the Maine Historical Society, 1893

- ^ Austin J. Coolidge & John B. Mansfield, A History and Description of New England; Boston, Massachusetts 1859

- ^ Joseph Conforti, "Creating Portland: History and Place in Northern New England;" Lebanon, New Hampshire 2005

- ^ p.431

- ^ Louis Arthur Norton, "Henry Mowat: Miscreant of the Maine Coast," Maine History, March 2007, Vol. 43 Issue 1, pp 1-20,

- ^ "Colin Woodard, Why the Royal Navy burned Portland in 1775; The Working Waterfront 2009". Archived from the original on 2008-10-12. Retrieved 2008-08-05.

- ^ James L. Nelson, "Burning Falmouth," MHQ: Quarterly Journal of Military History, Autumn 2009, Vol. 22 Issue 1, pp 62-69

- ^ Austin J. Coolidge & John B. Mansfield, A History and Description of New England; Boston, Massachusetts 1859

- ^ William Willis, History of Portland, Maine from 1632 to 1865; Bailey & Noyes, Portland, Maine 1865

- ^ William Willis, History of Portland, Maine from 1632 to 1865; Bailey & Noyes, Portland, Maine 1865

- ^ Sears, Donald A. (1978). John Neal. Boston, Massachusetts: Twayne Publishers. p. 124, quoting Edward C. Kirkland. ISBN 080-5-7723-08.

- ^ Kayorie, James Stephen Merritt (2019). "John Neal (1793-1876)". In Baumgartner, Jody C. (ed.). American Political Humor: Masters of Satire and Their Impact on U.S. Policy and Culture. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. p. 87. ISBN 9781440854866.

- ^ Sears, Donald A. (1978). John Neal. Boston, Massachusetts: Twayne Publishers. p. 123. ISBN 080-5-7723-08.

- ^ Richards, Irving T. (1933). The Life and Works of John Neal (PhD). Harvard University. p. 576. OCLC 7588473.

- ^ "George J. Varney, History of Portland, Maine; Boston, Massachusetts 1886". Archived from the original on July 9, 2012. Retrieved 2008-08-05.

- ^ William Willis, History of Portland, Maine from 1632 to 1865; Bailey & Noyes, Portland, Maine 1865

- ^ Babcock, Robert H. "Will You Walk? Yes, we'll Walk!: Popular Support for a Street Railway Strike in Portland, Maine." Labor History, vol. 35, no. 3, 1994, pp. 372-398.

- ^ Mooney, James L. Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships (1959-1981)

- ^ Morison, Samuel Eliot (1975). History of United States Naval Operations in World War II, Volume I The Battle of the Atlantic 1939-1943. Little, Brown and Company. p. 68.

- ^ "U.S.Navy Activities World War II by State". U.S. Naval Historical Center. Retrieved 2012-03-07.

- ^ "Bayside is a journey of many 'next steps'". Portland Press Herald (Blethen Maine Newspapers, Inc.). 2006-10-16. Archived from the original on 2006-10-22. Retrieved 2006-11-13.

- ^ Bouchard, Kelley (2006-10-06). "Riverwalk: Parking garage due to rise; luxury condos to follow". Portland Press Herald (Blethen Maine Newspapers, Inc.). Retrieved 2006-11-13.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Turkel, Tux (2007-02-06). "An urban vision rises in Bayside". Portland Press Herald (Blethen Maine Newspapers, Inc.). Archived from the original on 2007-12-26. Retrieved 2007-02-27.

- ^ Herald, Marketing DepartmentPortland Press (2015-12-02). "The word on the street (names)". Press Herald. Retrieved 2023-08-08.

- ^ The Origins of the Street Names of the City of Portland, Maine as of 1995 – Norm and Althea Green, Portland Public Library (1995)

Further reading

[edit]- Chen, Xiangming, ed. Confronting Urban Legacy: Rediscovering Hartford and New England's Forgotten Cities (2015) excerpt

- Michael C. Connolly. Seated by the Sea: The Maritime History of Portland, Maine, and Its Irish Longshoremen (University Press of Florida; 2010) 280 pages; Focuses on the years 1880 to 1923 in a study of how an influx of Irish immigrant workers transformed the city's waterfront.