History of Tottenham Hotspur F.C.

Tottenham Hotspur Football Club is a football club based in Tottenham, north London, England. Formed in 1882 as "Hotspur Football Club" by a group of schoolboys, it was renamed to "Tottenham Hotspur Football Club" in 1884, and is commonly referred to as "Tottenham" or "Spurs". Initially amateur, the club turned professional in 1895. Spurs won the FA Cup in 1901, becoming the first, and so far only non-League club to do so since the formation of the Football League. The club has won the FA Cup a further seven times, the Football League twice, the League Cup four times, the UEFA Cup twice and the UEFA Cup Winners' Cup in 1963, the first UEFA competition won by an English team. In 1960–61, Tottenham became the first team to complete The Double in the 20th century.

Tottenham played in the Southern League from 1896 until 1908, when they were elected to the Football League Second Division. They won promotion to the First Division the following year, and stayed there until the late 1920s. The club played mostly in the Second Division until the 1950s, when it enjoyed a revival, reaching a peak in the 1960s. Fortunes dipped after the early 1970s, but resurged in the 1980s. Tottenham was a founding member of the Premier League in 1992; they finished in mid-table most seasons, but now rank as one of the top six clubs.

Of the club's thirty-two managers, John Cameron was the first to win a major trophy, the 1901 FA Cup. Peter McWilliam added a second FA Cup win for the club in 1921. Arthur Rowe developed the "push and run" style of play in the 1950s and led the club to its first league title. Bill Nicholson oversaw the Double winning side as well as the most successful period of the club's history, in the 1960s and early 1970s. Later managers include Keith Burkinshaw, the second most successful in terms of major trophies won, with two FA Cups and a UEFA Cup, and Terry Venables, under whom the club won the FA Cup in 1991.

Spurs played their early games on public land at Tottenham Marshes, but by 1888 they were playing on rented ground at Northumberland Park. In 1899, the club moved to White Hart Lane, where a stadium was gradually developed. Spurs remained there until 2017. Its replacement, Tottenham Hotspur Stadium, was completed in 2019 on the same site; during its construction, home matches were played at Wembley Stadium.

Formation

[edit]On the 5th of September, 1882, the subscriptions to the club were commenced to be received, and the same, augmented by a small sum from the Cricket Club, were expended in purchasing wood for goal and flag posts, material for flags, tape (there were no cross-bars then), stationery and stamps, and later, a ball. The goal posts, one of which is still in existence, were of amateur make and made by Mr. Casey, the father of two of the members, and painted blue and white; the first ball was given by the big brother of the same two members, and he had some time back suggested the name of 'Hotspur' when the Cricket Club started.

The actual founders of the Football Club were: J. Anderson, T. Anderson, E. Beavan, R. Buckle, H.D. (Sam or Ham) Casey, L.R. Casey, F. Dexter, S. Leaman, J.H. Thompson, Jnr., P. Thompson, and E. Wall. R. Buckle was captain, H.D. Casey the vice-captain, J.H. Thompson, Jnr. the secretary, and L.R. Casey the treasurer.

The Hotspur Football Club was formed in 1882 by a group of schoolboys from Saint John's Middle Class School and Tottenham Grammar School. Mostly aged 13 to 14, the boys were members of the Hotspur Cricket Club formed two years earlier.[1] Robert Buckle with his two friends Sam Casey and John Anderson conceived the idea of a football club so they could continue to play sport during the winter months. Club lore states that the boys gathered one night under a lamppost along Tottenham High Road about 100 yards/metres from the now-demolished White Hart Lane ground, and agreed to form a football club.[2] The date of their meeting is unknown, so the Hotspur Football Club is taken to have been formed on 5 September 1882, when the eleven boys had to start paying their first annual subscriptions of sixpence.[3] By the end of the year the club had eighteen members.[1] Although the name Northumberland Rovers was mooted, the boys settled on the name Hotspur. As with the cricket club, it was chosen in honour of Sir Henry Percy (better known as Harry Hotspur, the rebel of Shakespeare's Henry IV, part 1), whose Northumberland family once owned land in the area, including Northumberland Park in Tottenham, where the club is located.[4]

The boys initially held their meetings under lampposts in Northumberland Park or in half-built houses on the adjoining Willoughby Lane in Tottenham. In August 1883 the boys sought the assistance of John Ripsher, the warden of Tottenham YMCA and Bible-class teacher at All Hallows Church, who became the first president of the club and its treasurer.[5][6] A few days later he presided over a meeting of twenty-one club members in the basement kitchen of the YMCA at Percy House or its annex on the High Road, which became the club's first headquarters. Ripsher, who continued as president until 1894, supported the boys through the club's formative years, reorganising it and establishing the club's ethos.[7] The stability he provided in the early years helped the club survive, unlike many others of the period that did not.[8] Ripsher found new premises for the club when the boys were evicted in 1884 after a YMCA council member was accidentally hit by a soot-covered football: first at 1 Dorset Villa, a church-owned property on Northumberland Park where they stayed for two years, then to the Red House on High Road around 1885–86 after they were again asked to leave, this time for playing cards in church.[9][10] The Red House, which stood beside the entrance gate to White Hart Lane but was demolished in 2016 during the ground's redevelopment,[11] was the club's headquarters until its move to 808 High Road in 1891. It was later bought by the club in 1921 and became its official address (748 Tottenham High Road) in 1935.[12][13] In April 1884, owing to letters for another London club named Hotspur being misdirected to North London, the club was renamed Tottenham Hotspur Football Club to avoid any further confusion.[14][15] The team were referred to as "Spurs" in press reports as early as 1883[16][17] (the use of "Spurs" for a team called Hotspur predates the formation of Tottenham Hotspur),[a] and they have also been called "the Lilywhites" after the white jerseys they have worn since the late 19th century.[18][19]

Early years

[edit]

The boys played their early matches on public ground at Tottenham Marshes, where they needed to mark out and prepare their own pitch, and on occasions had to defend against other teams who might try to take it over.[2] Local pubs were used as dressing rooms. Robert Buckle was the team's first captain,[20] and for two years the boys largely played games among themselves, but the number of friendly fixtures against other clubs gradually increased. The first recorded match took place on 30 September 1882 against a local team named the Radicals, a game Hotspur lost 2–0.[21] The first game reported by the local press was on 6 October 1883 against Brownlow Rovers, which Spurs won 9–0.[16] The team played their first competitive match on 17 October 1885 against St Albans, a company works team, in the London Football Association Cup. The match was attended by 400 spectators, and Spurs won 5–2.[22] In the early days Spurs were essentially a schoolboy team, sometimes playing against adults, but older players later joined, and the squad strengthened as they absorbed players from other local clubs.[3] Some of the early members such as Buckle, Sam Casey, John Thompson and Jack Jull stayed with the club for many years as players, committee members or directors; for example Jull played until 1896, while Buckle served in various roles on the club committee and was on the first board of directors of Tottenham formed in 1898 until he left in 1900.[23][24]

Spurs attracted the interest of the local community soon after their formation, and the number of spectators for their matches grew to 4,000 within a few years. As their games were played on public land, no admission fees could be charged for spectators. In 1888 Tottenham moved their home fixtures from the Tottenham Marshes to Northumberland Park, where they rented an enclosed ground and were able to charge for admission and control the crowd. The first match there was on 13 October 1888, a reserve match that yielded gate receipts of 17 shillings.[23] A week later they were beaten 8–2 by Old Etonians in their first senior game at the ground.[20] Spectators were usually charged 3d a game, raised to 6d for cup ties. By the early 1890s, a cup tie may draw a few thousand paying supporters.[23] In the early days there were no stands except for a couple of wagons as seats and wooden trestles for spectators to stand on, but for the 1894–95 season, the first stand with just over 100 seats and a changing room underneath was built on the ground.[25] The club attempted to join the Southern League in 1892 but failed when it received only one vote.[26] Instead, the club played in the short-lived Southern Alliance for the 1892–93 season.[27]

Spurs initially played in navy-blue shirts with a letter H on a scarlet shield on the left breast and white breeches.[28] The club colours were changed in 1884 or 1885 to light blue and white halved jerseys and white shorts, inspired by watching Blackburn Rovers win the FA Cup at the Kennington Oval in 1884, before returning to the original dark blue shirts for the 1889–90 season.[29] From 1890 to 1895, the club had red shirts and blue shorts, changed in 1895 to chocolate brown and gold narrow striped shirts and dark-blue shorts.[30] Finally, in the 1898–99 season, the strip was changed to the now familiar white shirts and navy-blue shorts.[31]

Professional status

[edit]The club became unwittingly involved in a controversy known as the Payne Boots Affair in October 1893. A reserve player from Fulham, Ernie Payne, agreed to play for Spurs but arrived without any kit as it had apparently been stolen at Fulham. As no suitable boots could be found, the club gave him 10 shillings to buy his boots. Fulham then complained to the London Football Association that Tottenham had poached their player, and accused them of professionalism breaching amateur rules. On the latter charge, the London Football Association found Tottenham guilty, as the payment for the boots was judged an "unfair inducement" to attract the player to the club.[23] Spurs were suspended for a fortnight, had to forfeit their second-round match against Clapham Rovers in the FA Amateur Cup and were therefore eliminated from the competition.[32] Despite the punishment, the controversy had an unexpected positive effect on the club. Press coverage of the incident raised the national profile of what was then a local amateur club, and gained them sympathy for what many thought was unfair treatment. Invitations from other clubs to play games increased, and attendance at their matches rose.[33] The publicity also brought on board local businessman John Oliver, who became chairman in 1894 after Ripsher retired, and provided funding for the club.[34]

With an increasing number of teams to play against, the quality of Spurs' opposition also improved. To compete against better teams, the club committee, led by the second club president John Oliver, agreed that the club should turn professional. Robert Buckle made the proposal at a meeting on 16 December 1895, which was accepted after a vote, and the club gained its professional status on 20 December 1895. Spurs made a failed attempt to join the Football League, but they were admitted to Division One of the Southern League in mid-1896.[35] They also participated in other leagues, initially the United League and later Western League, in which they did not always field the full first team.[23][36] The team was almost entirely rebuilt over the next two years; the first two professional players, Jock Montgomery and J. Logan, were quickly recruited from Scotland (a number of Scottish footballers would have significant influences in the club's history), and in 1897 they signed their first international, Jack Jones.[36]

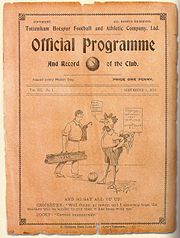

On 2 March 1898, Spurs decided to become a limited company—the Tottenham Hotspur Football and Athletic Company—to raise funds and to limit the personal liability of its members. Eight thousand shares were issued at £1 each, but only 1,558 were taken up by the public in the first year.[37] A board of directors was formed with Oliver as chairman, but he retired after the company reported a loss of £501 at the end of the season in 1899.[23] Charles Roberts took over as chairman and remained in the post until 1943.[38]

Soon after the club became a limited company, on 14 March 1898, Frank Brettell was appointed the first manager of Spurs.[39] He signed several players from northern clubs, including Harry Erentz, Tom Smith and, in particular, John Cameron, who signed from Everton in May 1898 and was to have a considerable impact on the club. Cameron became player-manager the following February after Bretell left to take a better-paid position at Portsmouth, and led the club to its first trophies: the Southern League title in 1899–1900 and the 1901 FA Cup. In his first year as manager, Cameron signed seven players: George Clawley, Ted Hughes, David Copeland, Tom Morris, Jack Kirwan, Sandy Tait and Tom Pratt. The following year Sandy Brown replaced Pratt, who wanted to return to the North despite being the top goalscorer. They, together with Cameron, Erentz, Smith and Jones, formed the 1901 Cup-winning team.[40]

Move to White Hart Lane

[edit]

On Good Friday 1898 a match was held against Woolwich Arsenal at Northumberland Park, attended by a record crowd of 14,000. In the overcrowded ground, fans climbed up onto the roof of the refreshment stand to get a better view. The stand then collapsed under their weight causing a few injuries, which prompted the club to start looking for a new ground. In 1899 the club moved a short distance to a piece of land behind the White Hart pub.[41] The White Hart Lane site, actually located behind Tottenham High Road, was a nursery owned by the brewery chain Charringtons. The club initially leased the ground from Charringtons, but development of the ground was restricted by the terms of the lease. In 1905, after issuing shares towards the cost of purchase, Spurs bought the freehold for £8,900 and paid a further £2,600 for a piece of land at the northern end.[42] By then the ground had a covered stand on the west side and earth mounds on the other three sides.[43]

The ground was never officially named, but it became popularly known as White Hart Lane, also the name of a local thoroughfare.[44] The first game at White Hart Lane was a friendly against Notts County on 4 September 1899 that Spurs won 4–1,[45] and the first competitive game on the ground was held five days later against Queens Park Rangers, a game won by Spurs 1–0.[46] With an effective attacking triangle of Jones, Kirwan and Copeland, Tottenham won 11 games in their first 13 games in the 1908–09 season. On 28 April 1900, they finished top of the Southern League, and won the club their first trophy.[47] After the win, the club was dubbed "Flower of the South" by the press.[48]

1901 FA Cup

[edit]Tottenham first took part in the FA Cup in the 1894–95 season, but never got beyond the third round proper in six years.[49] In the 1901 FA Cup, Spurs managed to reach the final after beating Preston North End, Bury, Reading and West Bromwich Albion; all apart from Reading were Football League Division One teams of the 1900–01 season. The final against Division One Sheffield United was played at Crystal Palace and attended by 110,820 spectators, at that time the largest crowd ever for a football match.[50] The game ended in a 2–2 draw, with both of Spurs' goals coming from Sandy Brown, and a disputed goal from Sheffield. The final was the first to be filmed, and it contained the first referee decision demonstrated by film footage to be incorrect, as it showed that the ball did not cross the line for the Sheffield goal.[50][51]

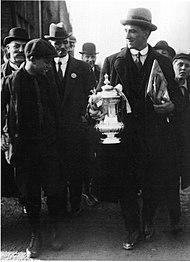

In the replay at Burnden Park, Bolton on 27 April 1901, Spurs won 3–1 with goals from Cameron, Smith and another by Brown. By winning the FA Cup, Spurs became the only non-League club to have achieved the feat since the formation of the Football League in 1888.[52] The club also inadvertently introduced the tradition of tying ribbons in the colours of the winning team on the FA Cup when the wife of a Spurs director tied blue and white ribbons to the handles of the cup.[53] The win started a trend for Spurs' success in years ending in a one, with further FA Cup wins in 1921, 1961, 1981 and 1991, the League Cup in 1971, the league in 1951, and in 1961, which is the double winning year.[54]

Following the 1901 Cup win, Spurs failed to repeat the success in the next few seasons but they were runners-up in the Southern League twice, and won the London League in the 1902–03 season as well as the Western League in the 1903–04 season.[55][56] They went on their first overseas tour, to Austria and Hungary, in May 1905.[57] Cameron left on 13 March 1907, citing "differences with the directorate",[23][58] and he was replaced in April 1907 by Fred Kirkham, a referee with no managerial experience. Kirkham was disliked by players and fans alike, and he left on 20 July 1908 after a year as manager.[59]

Early decades in the Football League (1908–1949)

[edit]Election to the Football League

[edit]Tottenham resigned from the Southern League in 1908 and sought to join the Football League. Their initial application was unsuccessful, but after the resignation of Stoke from the league for financial reasons, Tottenham won election to the Second Division of the Football League for the 1908–09 season to replace them.[60] As Spurs had no manager following Kirkham's departure, the directors took on the role of choosing the team, while the club secretary Arthur Turner was tasked with overseeing the team's affairs.[61] Spurs played their first league game in September 1908 against Wolverhampton Wanderers and won 3–0, with their first ever goal in the Football League scored by Vivian Woodward.[62] Woodward was also instrumental in the club's immediate promotion to the First Division after finishing runners-up in their first year. Before the start of the following season, Woodward left football to pursue other interests, although he soon returned to the game and joined Chelsea. Spurs struggled in their first year in the First Division, but avoided relegation by beating Chelsea in the last game of the season with goals from Billy Minter and a former Chelsea player Percy Humphreys, sending their opponents down instead.[63]

The club started an ambitious plan to redevelop White Hart Lane in 1909, beginning with the construction of the West Stand designed by Archibald Leitch. The North and South stands were then built in the early 1920s, with the East Stand completed in 1934, bringing the capacity of the finished stadium to almost 80,000.[42] A bronze cockerel was placed on top of the West Stand in 1909. The cockerel was adopted as an emblem because Harry Hotspur, after whom the club was named, was believed to have gained the nickname wearing fighting spurs in battles, and spurs were also worn by fighting cock.[64] Tottenham had initially used spurs as a symbol in 1900, as Harry Hotspur was said to have charged into battles by digging in his spurs to make the horse go faster, a symbol that evolved into a fighting cock.[65]

In April 1912 Jimmy Cantrell, Bert Bliss and Arthur Grimsdell arrived at the club.[66] Late that year Peter McWilliam was appointed manager. He became a significant and popular figure at the club, managing the team in two separate periods, both interrupted by world wars.[67] The first significant signing by McWilliam was winger Fanny Walden, who was signed for a record £1,700 in April 1913,[68] later signings included goalkeeper Bill Jaques and right-back Tommy Clay.[69] McWilliam's record in the early years was poor, and Tottenham were bottom of the league at the end of the 1914–15 season when league football was suspended owing to the First World War that had started a year earlier. During the war years, White Hart Lane was taken over by the government and turned into a factory for making gas masks, gunnery and protection equipment.[70] The London clubs organised their own matches, and Tottenham played their home games at Arsenal's Highbury and Clapton Orient's Homerton grounds.[71]

When football resumed in 1919, the First Division was expanded from 20 to 22 teams. The Football League offered one of the additional places to 19th-placed Chelsea, who would otherwise have been relegated with Spurs for the 1915–16 season, and the other, controversially, to Arsenal, who had finished only sixth in Division Two the previous season.[72][73] This decision cemented a bitter rivalry that continues to this day,[30] a rivalry that had begun six years earlier when Arsenal relocated from Plumstead to Highbury, a move opposed by Tottenham, who considered Highbury their territory, as well as by Clapton Orient and Chelsea.[74][75] Matches between the two clubs, called the North London derby, became the most fiercely-contested derby in London.[76]

Interwar years

[edit]

In the first season after the war McWilliam took Tottenham straight back to Division One when they became Division Two Champions of the 1919–20 season. They won with what was then a league record of 70 points, losing only 4 games all season with 102 goals scored.[77] Two players signed that season, Jimmy Dimmock and Jimmy Seed, became crucial members of the team together with Grimsdell.[78] Other notable players of the period include Tommy Clay, Bert Smith and Charlie Walters. The following year Spurs reached their second FA Cup final after beating Preston North End in the semi-final with two goals from Bliss. On 23 April 1921, in a game dominated by Walters, Spurs beat Wolverhampton Wanderers 1–0 in the final at Stamford Bridge, with 20-year-old Dimmock scoring the winning goal.[79][80] They also won their first Charity Shield the same year. Following their FA Cup victory in 1921, Spurs players started to wear the cockerel emblem on their shirts.[30]

At McWilliam's instigation a nursery club was established at Northfleet in about 1922, an arrangement that was formalised in 1931 and lasted until the Second World War.[81][82] Thirty-seven Spurs players, nine of whom became internationals, started their playing career at Northfleet. They include Bill Nicholson, Ron Burgess, Taffy O'Callaghan, Vic Buckingham and Ted Ditchburn.[82]

In the 1921–22 season, Spurs finished second to Liverpool in the league, their first serious challenge for the title. After the success of the two post-war seasons, Spurs only managed to finish mid-table in the next five. The team had begun to deteriorate, and new signings Jack Elkes and Frank Osborne could not overcome weaknesses in other positions.[83] They were in first place for a while in 1925, until Grimsdell broke his leg and they dropped down the table.[80] McWilliam left for Middlesbrough in February 1927 when Middlesbrough offered him significantly better pay while the Tottenham board refused his request for a smaller increase.[84] Billy Minter, who first joined the club as a player in 1907 and became the first player to score 100 goals for the club in 1919,[85] took over as manager. In the 1927–28 season, his first full season in charge, Spurs were unexpectedly relegated despite finishing with 38 points, only 6 points behind 4th-placed Derby County. One factor in their relegation may have been the sale of Jimmy Seed to Sheffield Wednesday—Wednesday had looked certain to be relegated, but Seed helped them escape, beating Tottenham twice along the way, and they went on to win the League Championship title in each of the next two seasons.[86]

Minter struggled to return Spurs to the top flight despite signing Ted Harper in February 1929. Harper was a prolific goalscorer in the few years he was at the club; his 36 league goals scored in a season in 1930–31 remained a record until 1963, when it was broken by Jimmy Greaves.[87][88] The stress of being manager affected Minter's health; he resigned, and was given another position at the club in November 1929.[89] Percy Smith was appointed manager at the start of 1930, and he strengthened the team with imported and home-grown talents including George Hunt, Willie Hall and Arthur Rowe. The team, aided by the goal-scoring exploits of Hunt, were nicknamed the "Greyhounds" in the 1932–33 season as they raced up the Second Division from near the bottom of the table, and won promotion after finishing second to Stoke City.[90] Spurs only managed to stay in Division One for two seasons; injuries (especially to Rowe and Hall) left the team weakened and at the bottom of the table in the 1934–35 season by April 1935. Smith then resigned, claiming that the club's directors had interfered with his team selection.[91]

Jack Tresadern took over from caretaker manager Wally Hardinge in July 1935, but failed to lift the club out of the Second Division in the three years of his tenure. He promoted centre-forward Johnny Morrison in place of fans' favourite George Hunt, and decided to sell Hunt to rival Arsenal in 1937, a decision that made him unpopular. He left in April 1938 for Plymouth Argyle when it became apparent that he would likely be sacked at the end of the season.[92] Peter McWilliam was brought back as manager, and he tried to rebuild the team by promoting young players from Northfleet including Nicholson, Burgess and Ditchburn, but his second stint at the club was again interrupted by world war.[67] Spurs also failed to advance beyond the quarter-finals of the FA Cup in the 1930s, getting that far three years running from 1935 to 1938. Despite Tottenham's lack of success in this period, 75,038 spectators still squeezed into White Hart Lane in March 1938 for a cup tie against Sunderland—the club's largest gate until it was surpassed in 2016 when more than 85,000 attended the 2016–17 UEFA Champions League home match against Monaco held at Wembley Stadium.[93]

War and post-war lull

[edit]On 3 September 1939 Neville Chamberlain declared war, and league football was abandoned with only three games played. Nevertheless, matches continued to be arranged and played during the Second World War. The London clubs first played in the Wartime League and Football League War Cup, and Spurs won the Regional League South 'C' in 1940. After a reorganisation in 1941, they also competed in the Football League South. Owing to the difficult wartime conditions, Spurs along with other London clubs refused to travel long distances for the matches drawn up by the Football League and decided to run their own competitions: London War League and London War Cup. They (eleven London clubs and five other clubs from the south) were temporarily expelled from the Football League; after paying a £10 fine they were readmitted, but they played in the Football League South in the way the London clubs had suggested.[94] McWilliam went back to the North during the war and the team was managed by Arthur Turner; under him Spurs won the regional league twice.[95][96] Charles Robert who had been chairman since 1898 died in 1943, and he was replaced by Fred Bearman.[97] As it was difficult to field a full squad in the war years, many young players, among them Sonny Walters, Les Medley, Les Bennett and Arthur Willis, gained their first playing experience for the club in this period.[94] Spurs also shared White Hart Lane with Arsenal when Highbury was requisitioned by the government and used as an Air Raid Precautions centre.[98]

After the war ended, McWilliam decided that he was too old to return to the club, and a former Arsenal player Joe Hulme was given the job of managing Tottenham. Hulme failed to win promotion for the club, although Spurs managed to stay in the top half of the Second Division for the three seasons he was manager,[97] and they reached the semi-final of the FA Cup in 1948.[99] Players who joined the squad under Hulme include Eddie Baily, Len Duquemin, Harry Clarke and Charlie Withers. Football was popular in the post-war era, and although in the three post-war seasons during which Spurs languished in the Second Division, some games still drew large crowds, particularly for cup ties.[100] Hulme was sacked after he refused a suggestion to resign following an illness in March 1949.[99]

Arthur Rowe and title win (1949–1958)

[edit]League title

[edit]In May 1949 Rowe became Spurs manager at a salary of £1,500 a year. He inherited the squad assembled by Hulme except for the one crucial signing he made when he took over, Alf Ramsey.[101] Rowe introduced a new style of play, Push and run, which proved to be highly successful, and transformed the players into a team that were hard to beat in the 1949–50 season. Rowe started his tenure as manager with a 4–1 victory at Brentford, the beginning of an unbeaten run of 23 League and Cup games between 27 August 1949 and 14 January 1950. With a free-scoring attack force, the team won the Second Division convincingly with six games yet to play. They ended the season nine points in front, elevating them back into the top flight.[102][103]

After a shaky start to their 1950–51 season when they were trounced 4–1 at home by the Blackpool side of Stanley Matthews, Tottenham won eight consecutive games in October and November that included a 7–0 defeat of Jackie Milburn's Newcastle.[102] Some considered the team of this season the best in Tottenham's history;[104] guarding the goal was Ditchburn, one of Spurs' best ever goalkeepers, who was aided in defence by Ramsey, Clarke, and Willis; also influential were the captain Burgess and Nicholson, with the five forwards of Baily, Medley, Duquemin, Bennett and Walters completing the regular starting eleven.[102][105] They finished the season ahead of Manchester United by three points, having won their First Division Championship title in the penultimate game of the season by beating Sheffield Wednesday with a solitary goal from Duquemin. That was Tottenham's first ever League title.[106]

Spurs Way

[edit]The push and run tactics developed by Rowe were successful in his early years as manager.[107] Rowe credited McWilliam for learning to play a quick passing game,[108] which he developed into a style involving players playing in triangles, quickly laying the ball off to a teammate and running past the marking tackler to collect the return pass. Keeping to Rowe's maxim of "make it simple, make it quick", this method proved an effective way of moving the ball at pace with players' positions and responsibilities being totally fluid. It became an attractive fast-moving attacking style of play regarded by Tottenham fans to be the Spurs Way, which was adjusted and perfected in the later period under Bill Nicholson.[102][109]

The great fallacy is that the game is first and last about winning. It is nothing of the kind. The game is about glory, it is about doing things in style and with a flourish, about going out and beating the lot, not waiting for them to die of boredom.

Spurs finished second in the 1951–52 season, beaten to the title by a young Manchester United team. A bad winter and the poor state of the White Hart Lane pitch were contributory, as the "push and run" style of play required a good firm playing surface. The following years witnessed a period of decline, as great players aged but younger players such as Tony Marchi and Tommy Harmer were not yet experienced enough, and with injuries and other teams adapting to Spurs' revolutionary style of play, it meant a struggle for the once-dominant team.[102][111] Spurs could only finish tenth in the 1952–53 season. The "push and run" team also started to disperse; Medley, Willis, Bennett and Burgess left to join other teams while Nicholson moved into coaching.[102] In 1954 Rowe signed future captain Danny Blanchflower for a club record fee of £30,000. Blanchflower won the FWA Footballer of the Year twice while at Tottenham.[112]

Post-Rowe

[edit]The stress of managing the team had affected Rowe's health, and he suffered a breakdown in 1954; he resigned after falling ill again the following year. Rowe's assistant and long-time club servant Jimmy Anderson stepped into the breach as manager, but the season ended with Spurs in the lower half of the table.[113] With Blanchflower in the team, Ramsey was dropped from the line-up, and he soon left to start his managerial career with Ipswich Town, later guiding England to a World Cup win.[114] Spurs were almost relegated at the end of the 1955–56 season, finishing just two points above the drop zone. In the 1956–57 season, under the guidance of Bill Nicholson as coach, the creative pairing of Blanchflower and Harmer, and the scoring prowess of Bobby Smith, the club experienced a revival and finished in second place, albeit eight points behind the winners, the "Busby Babes" of Manchester United. Tottenham also fared well in the following season, finishing third.[115][116] As manager, Anderson started to build a new team by signing, bringing in or promoting some of the players who became members of the team that saw major success later: Cliff Jones, Terry Medwin, Peter Baker, Ron Henry, Terry Dyson, Maurice Norman and Smith.[117]

Bill Nicholson and the glory years (1958–1974)

[edit]

In October 1958, with the pressure of a poor start to the season and failing health, Anderson resigned, to be replaced by Bill Nicholson.[118] Nicholson had joined Tottenham as an apprentice in 1936, and the following sixty-eight years saw him serve the club in every capacity from boot room to president. He became the most successful Spurs manager, guiding Tottenham to major trophy success three consecutive seasons in the early 1960s: the double in 1961, the FA Cup and European Cup semi-final in 1962 and the Cup Winners' Cup in 1963.[119][120]

In Nicholson's first game as manager, on 11 October 1958, Spurs beat Everton 10–4, their then record win,[121] but the team finished 18th in the league in his first season in charge. In the following 1959–60 season, Spurs improved to third place in the league, two points behind the champions Burnley. They also beat Crewe Alexandra 13–2 in the 1959–60 FA Cup with five goals coming from Les Allen. It remains the highest scoring FA Cup tie of the 20th century and is still the club's record win.[122][123] In his first two years in charge, Nicholson made several signings—Dave Mackay and John White, the two influential players of the Double-winning team, as well as Allen and goalkeeper Bill Brown.[123]

Double winners

[edit]

The 1960–61 season started with a 2–0 home win against Everton, the beginning of a run of eleven wins.[124] The winning run was interrupted by a 1–1 draw against Manchester City, followed by another four wins before the unbeaten streak was broken by a loss to Sheffield Wednesday at Hillsborough in November.[125] It remained the best ever start by any club in the top flight of English football until it was surpassed by Manchester City in 2017.[126] The title was won on 17 April 1961 when Spurs beat the eventual runners-up Sheffield Wednesday at home 2–1, with three games still to play.[127]

In this Double-winning season only seventeen players were used in all forty-nine league and cup games, three of them playing only once.[116][128] The team was built around the quartet of Blanchflower, Mackay, Jones, and White; completing the side were Smith (top scorer of the season), Allen, Henry, Norman, Baker, Dyson and Brown, with Medwin, Marchi, and a young Frank Saul among the reserves.[128][129] Spurs reached the final of the 1960–61 FA Cup, beating along the way Sunderland 5–0 in the sixth-round replay and Burnley 3–0 in the semi-final. Spurs met Leicester City in the 1961 FA Cup final and won 2–0, with Smith scoring the first and setting up the second for Dyson,[127] helped in part by Leicester being effectively reduced to ten men owing to injury (no substitutions were allowed at that time). Spurs became the first team in England to win the Double in the 20th century, and the first since Aston Villa achieved the feat in 1897.[128][130]

First European triumph

[edit]

Tottenham competed for the first time in a European competition in the 1961–62 European Cup. Their first opponents were Górnik Zabrze, who beat Spurs 4–2. After the match the Polish press described Spurs players as "no angels"; in response, in the return leg at White Hart Lane, some Spurs fans dressed up as angels holding placards with slogans such as "Glory be to shining White Hart Lane", and other fans joined in by singing the refrains of "Glory Glory Hallelujah". Spurs won 8–1 to the sound of fans singing "Glory glory hallelujah, and the Spurs go marching on", which became an anthem for Tottenham from that night onwards.[131] Spurs eventually lost in the semi-final to the holders Benfica, who went on to win the competition.[132]

A month later Spurs won the FA Cup again after beating Burnley in the 1962 FA Cup final.[133] The first goal of the game was scored by Jimmy Greaves, who was signed in December 1961 for £99,999 (so as not to be the first £100,000 player).[134] Greaves became the top goal scorer for Tottenham with 220 league goals and 321 goals in all appearances for the club, and the most prolific scorer ever in the top tier of English football.[135]

In the 1962–63 European Cup Winners' Cup, Spurs reached the final, beating Rangers 8–4 on aggregate, Slovan Bratislava 6–2, and OFK Belgrade 5–2 on aggregate. Spurs' 5–1 win in the Cup Winners' Cup final against Atlético Madrid in Rotterdam on 15 May 1963, during which Terry Dyson scored a goal from 25 yards out, made Tottenham the first British team to win a European trophy.[136]

Continuing success

[edit]By 1964 the Double-winning side was beginning to break up owing to age, injuries and transfers. Captain Danny Blanchflower hung up his boots that spring at the age of 38, troubled by a knee injury, and Dave Mackay was sidelined for a long period with his leg broken twice—the first occurred during Spurs' defence of the Cup Winners' Cup against Manchester United, resulting in the 10-men Spurs being eliminated from the competition.[137] In the summer of 1964, John White was tragically killed by lightning on a golf course.[138] Nicholson rebuilt the team with new players, most of them imports, including Alan Mullery, Pat Jennings, Cyril Knowles, Mike England, Terry Venables, Jimmy Robertson, Phil Beal, Joe Kinnear, and Alan Gilzean who formed a goal-scoring partnership with Greaves.[139] The rebuilding culminated in a win at the 1967 FA Cup final over Chelsea with goals from wingers Robertson and Saul, and a third-place finish in the league.[140][141]

The team failed to make much of an impact in the following two seasons, reaching only in 1969 the semi-final of the League Cup, a competition created in 1960 but one in which Tottenham did not participate until 1966.[142] Mackay, Jones and Robertson left the club in 1968, followed by Venables in 1969. In their place came the home-grown players Steve Perryman, Ray Evans and John Pratt,[142] and new signing Martin Chivers. Martin Peters also arrived from West Ham United for a record fee of £200,000 in 1970 in part-exchange for a reluctant Greaves,[142][143] while Ralph Coates was signed in the summer of 1971 for £192,000 from Burnley.[144] Gilzean recreated the goal-scoring partnership with Chivers that he had with Greaves, this time aided by the blindside runs of Peters.[145] The revitalised team reached the League Cup final in 1971, where they beat Aston Villa 2–0 to win their first League Cup with Chivers scoring both goals.[145] They won the League Cup again in 1973 after beating Norwich City by a single goal from Coates in the final.[146]

The 1971 Cup win and a third-place finish in the 1970–71 season earned Spurs a place in the inaugural UEFA Cup. They reached the final after a battling performance to draw against A.C. Milan at the San Siro stadium in the second leg of the semi-final, giving them a 3–2 win on aggregate.[147] In the first leg of the UEFA Cup final against Wolverhampton Wanderers, Chivers scored twice to give Spurs a 2–1 lead. In the return leg at White Hart Lane, team captain Mullery headed in a goal in his last game for the club for a 3–2 win on aggregate.[148][149] With this victory, Spurs became the first British team to win two different European trophies.[147] In total Nicholson had won eight major trophies in sixteen years; his spell in charge was the most successful period in the club's history.[119]

Decline and revival under Keith Burkinshaw (1974–1984)

[edit]Although Tottenham managed to reach four cup finals in four years and winning three of them from 1971 to 1974, the team began to decline as Nicholson was unable to sign the players he wanted, in part because of his refusal to meet the demands for under-the-counter payments.[150] The early seventies was also the beginning of a period of increasing football violence; rioting by Spurs fans in Rotterdam in their loss to Feyenoord in the 1974 UEFA Cup final added to his disillusionment. Nicholson resigned after a poor start to the 1974–75 season and a 4–0 loss to Middlesbrough in the League Cup, but his tenure ended on a sour note. He had sought to be succeeded by Blanchflower as manager and Johnny Giles as player-coach, but the chairman Sidney Wale was angered by Nicholson contacting the pair without informing him first. The club then severed all ties with a £10,000 payoff, even though Nicholson had wanted to stay on as an advisor, and refused him a testimonial (Nicholson was later brought back as advisor by Keith Burkinshaw and was only given a testimonial in 1983 under a different chairman).[151][152]

Terry Neill was appointed manager by the board, and Spurs narrowly avoided relegation at the end of the 1974–75 season. Spurs performed better the following season, in which Glenn Hoddle played his first game for the club. A former Arsenal player, Neill was never accepted by the fans, and he left to manage Arsenal in mid-1976, replaced by his assistant Keith Burkinshaw whom he had recruited the previous year.[153][154]

Relegation

[edit]In Burkinshaw's first year as manager in the 1976–77 season, Tottenham slipped out of the First Division after 27 years in the top flight. Many of the early '70s Cup-winning team had by now left or retired. This was followed in the summer of 1977 by the sale of their Northern Ireland international goalkeeper Pat Jennings for a bargain £45,000 to Arsenal as Burkinshaw had started to use Barry Daines, a move that shocked the club's fans and one that Burkinshaw later admitted was a great error. Jennings played on for another seven seasons for Spurs' arch-rivals.[155][156]

Despite relegation, the board kept faith with Burkinshaw and the team immediately won promotion to the top flight, although it took until the final league game of the season for them to be promoted. A sudden loss of form at the end of the 1977–78 season meant the club needed a point in the last game at Southampton. To Tottenham's great relief, the game ended 0–0 and Spurs returned to the First Division. Early in the season, Spurs had won 9–0 at home to Bristol Rovers, with four of their goals coming from debutant striker Colin Lee. The glut of goals proved significant later on as Tottenham won promotion through goal difference.[157]

Cup wins and European success

[edit]

In the summer of 1978, Burkinshaw caused a stir by signing for £750,000 two Argentinian internationals Osvaldo Ardiles and Ricardo Villa—players from beyond the British Isles in English football were rare at the time.[158] This was also a period of rebuilding as young players were brought in from the youth team, such as Mark Falco, Paul Miller, Chris Hughton and Micky Hazard, as well as other players signed from other clubs such as Graham Roberts, Tony Galvin, and in particular the twin strike force of Garth Crooks and Steve Archibald.[159][160]

Spurs opened the 1980s by reaching the 100th FA Cup final in 1981 against Manchester City, and won the replay 3–2 in a match notable for the winning goal from Ricardo Villa.[161] They lifted the FA Cup again the next season, beating Queens Park Rangers in the 1982 final. Although they were also in contention for three other trophies that season, they finished fourth in the First Division, lost to Liverpool in the League Cup final in extra time, while Barcelona won at home in the Cup Winners' Cup semi-final after a 1–1 draw at White Hart Lane.[162]

The club began a new phase of redevelopment at White Hart Lane in 1980, starting with the rebuilding of the West Stand initiated by a new chairman Arthur Richardson.[163] The West Stand was demolished and a new stand, which took 15 months to complete, opened in 1982. Cost overruns on the project, which rose from £3.5 million to £6 million, as well as the cost of rebuilding the team in the return to Division One resulted in financial difficulties for the club. In this period, property developer and Spurs fan Irving Scholar began buying up shares in the club. He took advantage of a rift in the boardroom between Richardson and former chairman Sidney Wale, and persuaded Wale to sell his shares.[163][164] Scholar bought up 25% of the club for £600,000, and with the help of Paul Bobroff who had bought 15% of shares from the family of previous chairman Bearman, took control in December 1982.[165][166] Scholar inherited a club in debt to the tune of nearly £5 million, what was then the largest debt in English football, but a rights issue after he took over brought in a million pounds. In 1983, a new holding company, Tottenham Hotspur plc, was formed with the football club run as a subsidiary of the company. With a valuation of £9 million, the company was floated on the London Stock Exchange, the first sports club to do so.[164][167] Together with Martin Edwards of Manchester United and David Dein of Arsenal, Scholar transformed English football clubs into business ventures that applied commercial principles to the running of the clubs to maximise their revenues, a process that eventually led to the formation of the Premier League.[168]

There used to be a football club over there.

The quote is actually by journalist Ken Jones and refers to the Frank Sinatra's song "There Used to Be a Ballpark". It is generally taken to be a comment on the commercialisation of football.[169][170]

In 1984, Tottenham reached the final of the UEFA Cup. After 1–1 scores in both legs against Anderlecht, Tottenham emerged the victor when Tony Parks saved a penalty in the penalty shootout.[171] This was the third of the major trophies won by the club under Burkinshaw in the 1980s. Several weeks before this victory, Burkinshaw announced that he would be leaving at the end of that season after disagreements with the directors and becoming disenchanted with the club.[172][170]

Shreeves and Pleat (1984–1987)

[edit]Burkinshaw was succeeded as manager by his assistant Peter Shreeves in June 1984. According to Scholar, Aberdeen manager Alex Ferguson, who joined Manchester United two years later, had reneged on an agreement to take over.[173] Tottenham enjoyed a strong start to the 1984–85 season and looked poised to win the league title by the winter, but a series of poor home results in 1985 resulted in the team being leapfrogged by eventual champions Everton and runners-up Liverpool.[164] Their final position of third place in the league should have secured them a UEFA Cup place, but the Heysel disaster on 29 May 1985, which saw 39 spectators crushed to death when Liverpool fans rioted at the 1985 European Cup final, resulted in all English clubs being banned from European competitions.[174] In 1986, Perryman departed after 19 years at the club (17 years in the first team) and a record 655 league appearances.[175] The same year Spurs also sold its training ground at Cheshunt that the club had owned since 1952 for over £4 million.[167] The 1985–86 season proved disappointing despite the signings of Chris Waddle and Paul Allen in the summer of 1985, and Shreeves was sacked at the end of the season.[174]

Luton Town manager David Pleat was appointed the new manager following Shreeves' dismissal. For much of 1986–87, Spurs played with what was for that time an unusual five-man midfield formation: Hoddle, Ardiles, Allen, Waddle and Steve Hodge.[176] The lone striker Clive Allen scored 49 goals in all competitions that season, still a club record.[177] Tottenham remained in contention for all three major domestic honours throughout the season, but finished the season empty-handed. In the League Cup, Tottenham lost to eventual competition winners Arsenal in the semi-final.[178] Spurs also missed out on the First Division title to Everton, and stumbled to a 3–2 loss in the FA Cup final to Coventry City, whose winning goal was deflected off Gary Mabbutt's knee for an own goal in the final minutes.[176][179] The close season of 1987 saw the sale of Glenn Hoddle to Monaco after a decade as the driving force in Tottenham's midfield.[176]

Terry Venables (1987–1993)

[edit]In October 1987, Pleat quit the club following allegations about his private life.[180] He was succeeded by former player Terry Venables, who had by then built up an impressive managerial record. He inherited a Spurs side that was struggling in the league with a quarter of the 1987–88 season played. Earlier in the season veteran goalkeeper Ray Clemence had to retire after suffering an Achilles tendon injury,[181] and new signings by Venables Terry Fenwick and Paul Walsh failed to lift the team, which finished in 13th place.[182] Striker Clive Allen was also less prolific in attack in this season, and he was sold to French club Bordeaux in March 1988.[183]

To invigorate the Tottenham side, Venables paid a national record £2 million for Newcastle midfielder Paul Gascoigne in June 1988, and also signed striker Paul Stewart from Manchester City for £1.7 million.[184] Spurs made a shaky start to the 1988–89 season; incomplete refurbishment of the East Stand caused the postponement of the opening game against Coventry just a few hours before kickoff, which earned the club a two-point deduction (later replaced by a £15,000 fine), and this was followed by a string of losses in October.[185] They were second from bottom at the end of October, but improved to ninth place by the turn of 1989 and finished sixth in the final table.[186]

Cup win and boardroom drama

[edit]By the end of the 1980s and the beginning of 1990s, Spurs had become mired in considerable financial difficulties, with a debt reported to be £20 million in 1991.[187] The East Stand was refurbished in 1989 but its cost had doubled to over £8 million, while the company's attempts to diversify into other businesses such as the clothing firms Hummel UK and Martex failed to generate the income expected and were in fact losing them money.[167][188] July 1989 saw the arrival at White Hart Lane of England striker Gary Lineker from Barcelona for a fee of £1.2 million; however, the cash-strapped club was unable to pay Barcelona in full even though Waddle was sold days later to Marseille for £4.25 million.[182] Scholar had to organise a secret £1.1 million loan from Robert Maxwell, which caused an uproar and resulted in an attempt to oust Scholar from the boardroom when it was revealed.[188][189] Maxwell, who first owned Oxford United and then Derby County, became interested in the club, putting Derby County up for sale so that he could acquire Tottenham.[167] Venables, who had previously attempted to buy the club but failed, then joined forces with businessman Alan Sugar in June 1991 to forestall a takeover by Maxwell and gain control of Tottenham Hotspur plc, buying out Scholar for £2 million.[165][190][191]

With Lineker and Gascoigne in the team, Spurs finished third in the 1989–90 title race won by Liverpool.[192] In the following 1990–91 season, they began the season unbeaten in ten games, but failed to rediscover their earlier league form in the second half of the season, eventually finishing tenth in the final table.[193][194] Despite the middling ranking, this season remains a highlight for Tottenham for their performances in the 1990–91 FA Cup. A 3–1 semi-final win over Arsenal featured a 30-yard free kick from Gascoigne considered to be one of the best goals ever seen in the competition.[195] In the final against Nottingham Forest, Gascoigne suffered serious cruciate ligament damage in his knee when he made a reckless tackle on opponent Gary Charles.[196] Winning the match 2–1 after extra time, Spurs became the first team to collect eight FA Cups, a record later surpassed by Manchester United in 1996.[197] The excitement in North London over the win also had the unexpected result of prompting Sugar, who had little knowledge of the club's history (and was alleged to have asked "What Double?" when someone mentioned Tottenham's Double),[198] to contact Venables and jointly buy the club.[199]

Gascoigne was a transfer target for Italian club Lazio, but his knee injury (aggravated later in a nightclub incident) meant that he missed the 1991–92 season, and his transfer to Lazio was put on hold. By the summer of 1992, his knee had recovered and he completed his move to Lazio for £5.5 million, reduced from the £7.9 million fees agreed before his injury.[199] Gary Lineker then announced in November that he would be leaving Spurs at the end of the season to play in Japan, while Paul Walsh and Paul Stewart also left the club.[199]

In the 1991–92 season, Venables became chief executive of the club, and Shreeves again took charge of first-team duties. During the summer of 1992, Venables decided to return to team management; Shreeves was sacked, and a European style of management was instituted with Doug Livermore the head coach and Clemence the assistant. Although Sugar and Venables began as equal partners with each investing £3.25 million in the club, Sugar's financial clout allowed him to increase his stake to £8 million in December 1991, thereby gaining control of the club.[199] In May 1993, after a row at a board meeting, Terry Venables was controversially dismissed from the Tottenham board by Sugar, whose decision was overturned in the High Court but reversed on appeal.[200] Despite being initially seen as a saviour of the club, the ousting of a popular figure, later aggravated by a perceived lack of investment in the club, earned Sugar long-lasting animosity from some fans who repeatedly called for his resignation.[201][191]

Beginning of Premier League football (1992–2004)

[edit]Spurs were one of the five clubs that pushed for the founding of the Premier League, created with the approval of The Football Association to replace the Football League First Division as the highest division of English football.[202] To coincide with the massive changes in English football, Tottenham made major signings, including winger Darren Anderton, defender Neil Ruddock,[199] and striker Teddy Sheringham for what was then a club record £2.1 million from Nottingham Forest. The Sheringham transfer was later the subject of allegations of "bungs" against Forest manager Brian Clough.[203] In the first ever Premier League season—Venables' final year as Spurs' manager—Spurs finished eighth. Teddy Sheringham was the division's top scorer with 22 goals, 21 of which were scored for Tottenham.[204]

Ardiles, Francis and Gross

[edit]The departure of Venables saw Tottenham return to a conventional management setup after two seasons of a two-tier structure. Former player Osvaldo Ardiles took charge of the first team. In the 1993–94 season, Sheringham's injury in October 1993 impacted on Spurs' performance, and relegation became a real possibility.[205] In the end, the club managed a 15th-place finish, its survival only guaranteed by a win in the penultimate game of the season.[206] By this time Spurs had come under investigation for financial irregularities alleged to have taken place in the 1980s while Irving Scholar was chairman, and in June 1994 the club was found guilty of making illegal payments to players. Spurs were fined £600,000, had twelve league points deducted for the 1994–95 season and were banned from the 1994–95 FA Cup. Following an appeal the number of points deducted was reduced, but the fine was increased to £1.5 million. A further arbitration (after Sugar threatened to sue the FA) quashed the points deduction and FA Cup ban, although the fine remained in place.[207]

Despite the penalty, the club aimed to have a successful season in 1994–95, and signed three players who had appeared at that summer's World Cup: German striker Jürgen Klinsmann and two Romanians, Ilie Dumitrescu and Gheorghe Popescu.[208][209] Forward players in Spurs line-up already included Sheringham, Anderton and Nick Barmby, and Ardiles chose to play five attacking players, dubbed the "Famous Five" of Klinsmann, Sheringham, Anderton, Barmby, and Dumitrescu.[210] Their debut in the 1994–95 season against Sheffield Wednesday in August 1994, which Spurs won 4–3, was described as a "breathtaking exhibition of football", but the imbalance in the team also leaked goals (33 in 15 games).[211][212] Spurs struggled in September with a series of defeats, and after the team lost 3–0 in the League Cup in October,[213] Ardiles was dismissed. At that time Spurs were just two places above the relegation zone, although they would have been 11th in the table with the deducted points that were later restored.[212]

Ardiles was replaced by Gerry Francis, who alleviated relegation fears and oversaw the club's climb to seventh place in the league, just missing out on a 1995–96 UEFA Cup place. When the FA Cup ban was lifted, Spurs reached the FA Cup semi-final where they were defeated 4–1 by eventual winners Everton.[214] Klinsmann was top scorer at the club with twenty-nine in all competitions, but he felt that Spurs would not be able to challenge for the title in future seasons, and returned to his homeland to sign with Bayern Munich.[215][216] Barmby, Dumitrescu and Popescu also departed, and Francis signed the likes of Ruel Fox and Chris Armstrong for more than £4 million each but spurned the chance to sign Dennis Bergkamp who was a fan of Glenn Hoddle and was interested in joining Spurs.[215][217] Other signings include future captain Ledley King who did not start in the first team for a few years. Francis' transfer dealings failed to deliver European qualification or higher, and Spurs finished eighth in 1996 and tenth in 1997. Sheringham left in the summer of 1997 for Manchester United while Les Ferdinand joined the team for a record £6 million and David Ginola for £2.5 million from Newcastle. Ferdinand was soon hit by injury, and in November 1997, Francis decided to resign after Spurs were beaten 4–0 by Liverpool.[218][219]

Christian Gross, coach of Swiss champions Grasshoppers, was chosen as the successor to Francis. Gross failed to turn around the club's fortunes in the 1997–98 season, and the team battled against the drop for the remainder of the campaign.[220] Klinsmann returned to Spurs in December on loan, and four goals in a 6–2 win away to Wimbledon in the penultimate game of the season was enough to secure survival. By the end of the season, the renovation of the White Hart Lane stadium was completed. White Hart Lane was converted into an all-seater stadium in the 1990s, the South Stand was rebuilt, and a new tier added to the North Stand, leaving the stadium with a capacity of about 36,240.[42] The stadium remained in this form bar some minor changes until 2016.[42]

George Graham and League Cup win

[edit]After losing two of the first three games of the 1998–99 season, Gross was sacked, and former Arsenal manager George Graham was hired to take over.[221][222] Graham signed Steffen Freund, who became a fans' favourite, as well as Tim Sherwood.[223][224] Fans were critical of Graham due to his association with Arsenal and disliked his defensive style of football, especially when Arsène Wenger was starting to achieve major success at Arsenal with an attacking football style previously associated with Spurs.[225] Nevertheless, in Graham's first season as Spurs manager, 1998–99, the club secured a mid-table finish and won the League Cup. In the final against Leicester City at Wembley Stadium, full-back Justin Edinburgh was sent off after an altercation with Robbie Savage, but the ten-men Spurs secured a dramatic victory through Allan Nielsen's diving header in the 93rd minute of the game.[226] To cap a good season, David Ginola won both the PFA Players' Player of the Year and Football Writers' Association Footballer of the Year awards in the year Manchester United won the Treble.[227][228]

The club finished mid-table the following year. In May 2000, Tottenham signed Ukrainian striker Serhii Rebrov from Dynamo Kyiv for a club record £11 million. But Rebrov was not a success at White Hart Lane, managing just ten goals over the next four seasons.[229]

New ownership and Glenn Hoddle

[edit]In late 2000, Sugar decided to sell his share holding in the club,[230] a decision he blamed on the hostility of fans towards him and his family.[231] 27% of his 40% share holding in Tottenham were sold for £22m to ENIC Sports PLC,[232][233] and he stepped down as chairman in February 2001 on the completion of the sale.[54][234] The rest of his shares were sold in 2007 for £25m.[235] ENIC, owned by Joe Lewis and Daniel Levy with the latter responsible for the running of the club, would eventually acquire 85% of Tottenham.[236][237] The club was transferred into its private ownership in 2012.[238] A month after Levy took over as chairman, George Graham was sacked as manager for alleged breach of contract by vice-chairman David Buchler after Graham commented on the financial position of Spurs.[239]

Team management passed to former Tottenham player Glenn Hoddle, who took over in the final weeks of the 2000–01 season from caretaker manager David Pleat. His first game was a defeat to Arsenal in the 2001 FA Cup semi-final.[240] That summer, club captain Sol Campbell joined Arsenal on a Bosman free transfer. The loss of a transfer fee by Spurs, the move to their bitterest rivals, and the perceived underhanded fashion in which he negotiated his move (claimed to be a record £100,000 per week)[241] led to long-term enmity towards Campbell from Spurs fans.[242] Hoddle turned to more experienced players in the shape of Teddy Sheringham who returned to Spurs in May 2001, as well as new signings Gus Poyet and Christian Ziege. Spurs played some encouraging football in the opening months of his management, but they ended the 2001–02 season in ninth place. They reached the League Cup final, where they lost to Blackburn, despite being seen as the favourites after their 5–1 defeat of Chelsea in the previous round.[243][244]

The only significant outlay before the following campaign was the £7 million signing of Robbie Keane, who joined from Leeds United. Jamie Redknapp also joined earlier on a free transfer.[245] The 2002–03 season started well, with Tottenham top of the league after three successive wins, and Hoddle voted manager of the month in the division for August.[245] They were still in the top six as late as early February, but the season ended with a tenth-place finish, the result of a barren final ten games of the league campaign that delivered a mere seven points. Several players publicly criticised Hoddle's management and communication skills. In the following 2003–04 season, Spurs started the season poorly, gaining only four points out of six games. With Spurs struggling third from bottom at the table, Hoddle was sacked by Levy, and Pleat again took over as caretaker manager.[246]

Resurgence and the Champions League (2004–2014)

[edit]

In June 2004, Tottenham appointed French team manager Jacques Santini as head coach, with Martin Jol as his assistant and Frank Arnesen as sporting director.[247] In early November, after only 13 games in charge, Santini decided to quit the club, making his the shortest stint by any Spurs manager.[248] Santini was replaced by Jol,[249][250] and the team managed to secure a ninth-place finish in the 2004–05 season. In June 2005, when Arnesen moved to Chelsea, Spurs appointed Damien Comolli as sporting director. Among the players signed by Jol were Edgar Davids in 2005,[251] Dimitar Berbatov in 2006,[252] and Gareth Bale in May 2007.[253] Players who left included Michael Carrick, who went to Manchester United for a reported £18.6 million in 2006.[254]

During the 2005–06 season, Spurs spent six months in the top four. Going into the final game of the season, they led Arsenal by a point, but were defeated in their final match—away to West Ham—after many players including Keane and Carrick succumbed to food poisoning from a meal they had the night before.[255] Spurs were pipped to a UEFA Champions League place, but gained a place in the UEFA Cup and achieved their highest finish for 16 years. In 2006–07, they finished fifth for the second-straight year.[256]

The 2007–08 season saw the club win only one of their first ten League matches, their worst start in 19 years. Jol was sacked, learning of his removal just before a UEFA Cup game on 25 October 2007.[257] Juande Ramos, formerly of Sevilla, then replaced the Dutchman as manager. Captained by Ledley King, Spurs went on to win the League Cup, beating Chelsea 2–1 in the League Cup final in February 2008.[258] Luka Modrić was signed towards the end of the season,[259] but Berbatov and Keane were sold to Manchester United and Liverpool respectively in the summer as both wanted to leave.[260] Tottenham made their worst start to a season in the club's history in 2008–09, their failure to register a win in eight League games leaving them bottom of the Premier League. Ramos and director of football Damien Comolli were dismissed on 25 October 2008, amid Levy's criticism of the failure to recruit suitable replacements for Berbatov and Keane.[261][262]

Harry Redknapp

[edit]Portsmouth manager Harry Redknapp was appointed as Ramos' replacement, and Tottenham reverted to a traditional setup with Redknapp responsible for both coaching and player transfers.[261][263] Redknapp took the club out of the relegation zone by winning 10 out of the 12 points available in his first two weeks in charge, and finished the 2008–09 campaign eighth in the league table. The January transfer window saw the return of Keane and Jermain Defoe to the club after spells at Liverpool and Portsmouth respectively,[264] later joined by Peter Crouch signed in the summer,[265] and Rafael van der Vaart in 2010.[266]

The team's performance improved in the two following seasons. Notable matches in the 2009–10 season include the 9–1 home win against Wigan Athletic, with Defoe scoring five, a record win in the top flight for the club,[268] and a 2–1 against Arsenal, with goals from Bale and debutant Danny Rose, giving them their first Premier League victory against their rivals.[269] Spurs finished the 2009–10 season in fourth place, and reached the qualifying rounds of the Champions League for the first time in their history.[270] In the 2010–11 season, they qualified for the group stages of the Champions League,[271] came top of their group and went on to beat A.C. Milan 1–0 on aggregate in the knockout stage.[272] At the quarter-finals, Spurs suffered a heavy defeat against Real Madrid after Crouch was sent off early in the game, and the 10-men team was beaten 4–0 at the Santiago Bernabéu Stadium, and 5–0 on aggregate.[273][274] Earlier in the season they won at the Emirates with goals from van der Vaart and Bale, their first win at Arsenal in 17 years.[267]

At the start of the 2011–12 season, the home league game to Everton was cancelled because of rioting in Tottenham a week before the game, and Spurs then lost the next two games.[275][276] Tottenham managed to record ten wins and one draw in their next eleven Premier League matches,[277] and finished the season in fourth place in the Premier League but failed to qualify for the Champions League.[278] On 13 June 2012, after brief contract renewal talks during which Redknapp and the Tottenham board failed to agree terms, Redknapp was dismissed by the club.[279]

Villas-Boas and Sherwood

[edit]Following Redknapp's departure, the club appointed former Chelsea and Porto coach André Villas-Boas as manager. Shortly after his appointment, the club pipped Liverpool for the signature of Swansea City midfielder Gylfi Sigurðsson. Several days later, the club also resolved the protracted transfer saga surrounding Ajax defender Jan Vertonghen.[280] They were soon followed by Hugo Lloris and Mousa Dembélé, while Modric left for Real Madrid.[281] In the 2012–13 season, they finished fifth. Despite winning a dramatic match against Sunderland with a goal from Gareth Bale in the final match of the season, Arsenal won their last match to take the 2013–14 Champions League spot, and Spurs dropped to the Europa League for the second successive season.[282] In their concurrent 2012–13 Europa League campaign, they were eliminated in the quarter-finals by Swiss side Basel on penalties.[283]

At the beginning of the 2013–14 season, Bale moved to Real Madrid for what was then a world record transfer fee of €100.8 million (£85.1 million).[284] This money paid for several players signed in that transfer window, including Christian Eriksen and Erik Lamela.[281] Following a 6–0 defeat against Manchester City and a 5–0 defeat against Liverpool, Villas-Boas was dismissed from his role on 16 December 2013.[285] A week later, former Spurs player Tim Sherwood became Villas-Boas' replacement as manager as a stopgap measure.[286][287] Although Sherwood led Spurs to a sixth-place finish in the Premier League,[288] his results against the top teams were disappointing, and he was sacked on 13 May 2014.[287][289]

Pochettino era (2014–2019)

[edit]

Mauricio Pochettino was appointed Tottenham manager on 27 May 2014, on a five-year contract.[290] In his first season Spurs finished fifth in the 2014–15 Premier League with 64 points, and were runners-up in the 2015 Football League Cup final. Pochettino chose to promote young players, and in his second season in charge, Spurs had the youngest team in the Premier League.[291][292] A new generation of players that included Harry Kane, Dele Alli, and Eric Dier were all aged 22 or younger that season.[293] Spurs had a much improved 2015–16 season, but their title challenge ended with a 2–2 draw at Stamford Bridge on 2 May 2016, and they finished third behind winners Leicester.[294][295] The following 2016–17 season began with a series of 12 unbeaten league matches, but the team performed inconsistently during the first half of the season.[296][297] They put in a much better performance in 2017, including a win in the North London derby that ensured a higher finish in the Premier League than their rivals Arsenal for the first time in 22 years.[298] Their early inconsistency meant that Spurs were unable to overhaul the lead of the eventual champions Chelsea in the league table (13 points over Spurs at one stage in March),[299] and finished the season in second place with 86 points, their highest ever points tally since the Premier League began.[300] This is their highest ranking in 54 years since the 1962–63 season under Bill Nicholson,[301] and the team also achieved their first unbeaten home run in 52 years since the 1964–65 season.[302][303]

New stadium

[edit]

The construction of a new stadium was initiated at on land adjacent to White Hart Lane in 2015.[304] The new stadium has a seating capacity of 62,062, considerably greater than the 36,000 of White Hart Lane. A section of the North Stand was removed to allow building work on the new stadium to proceed next to the old stadium.[305] The removal of part of the stand reduced the capacity of the stadium, and European matches were held at Wembley Stadium for the 2016–17 season to comply with the ticketing requirement for European games.[306] A club attendance record of 85,512 spectators was reported for the 2016–17 UEFA Champions League game against Bayer Leverkusen, which Spurs lost 1–0.[307] Spurs played their last game at White Hart Lane on 14 May 2017, a 2–1 victory over Manchester United that secured their second place in the Premier League.[308]

In the summer of 2017, White Hart Lane was demolished to allow the new stadium to be completed, and all Tottenham's home games were played at Wembley for the 2017–18 season.[309] As the stadium has a higher capacity, this season saw a series of record attendances for Premier League games, the highest at the North London Derby on 10 February 2018 when 83,222 spectators witnessed Spurs' 1–0 win over Arsenal.[310][311][312] Tottenham failed to make any new signings in the summer transfer window of 2018, the first club not to do so in the Premier League.[313] They also failed to sign anyone in the next transfer window in January.[314] They nevertheless had their best start in the Premier League in the 2018–19 season,[315] ended by a home defeat against Manchester City.[316] After some delay, the new stadium, Tottenham Hotspur Stadium, was completed and opened on 3 April 2019.[317] The first game at the stadium, the Premier League game against Crystal Palace, was won by Tottenham 2–0, with Son Heung-min scoring the first-ever official goal at the new stadium.[318]

Tottenham started the 2018–19 UEFA Champions League poorly, gaining only one point in the first three games of the group stage.[319] They managed to qualified for the knockout phase with a late equalising goal against Barcelona.[320] After beating Borussia Dortmund in the Round of 16, the team staged a dramatic win on away goals (4–4 on aggregate) against Manchester City in the quarter-final,[321][322] followed by a last-gasp victory over Ajax in the dying seconds of the semi-final, achieved with a hat-trick by Lucas Moura to overcome a 3–0 deficit on aggregate in the second half of the return leg. Tottenham reached their first ever Champions League final.[323][324] However, they were beaten 2–0 in an uninspiring final, and finished runners-up.[325]

José Mourinho, Nuno Espírito Santo, Antonio Conte, and Ange Postecoglou (2019–present)

[edit]The 2019–20 season started poorly for Tottenham, winning only three of their first 12 league games and struggled in the cup tournaments, including a disastrous 7–2 defeat to Bayern Munich in the Champions League group stage.[326] As a result, Pochettino was subsequently sacked on 19 November 2019, to be replaced by José Mourinho as coach the following day.[327][328] In a season disrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic, Mourinho failed to lift the team to qualify for the Champions League for the first time in five years, but managed to qualify for the 2020–21 Europa League.[329][330][331] In the following 2020–21 season, Tottenham had a good run of form in the first few months, with Harry Kane and Son Heung-min forming a formidable goal-scoring partnership, seeing Spurs to the top of the league table in late November following a win 2–0 against Manchester City.[332][333] However, a string of bad results saw them dropping down the league table through the second half of the season,[334][335] and Mourinho's defensive style of football further drew criticisms.[336][337] Mourinho was dismissed from Tottenham on 19 April 2021, just six days prior to the League Cup final, to be replaced by ex-Tottenham player and interim head coach, Ryan Mason, for the remainder of the season.[338][339] Tottenham lost 1–0 to Man City in the League Cup final and finished seventh in the league table, thereby qualifying for the inaugural 2021–22 UEFA Europa Conference League (UECL) but failing to qualify for either Champions or Europa Leagues the first time since the 2009–10 season.[340]

On 30 June 2021, Nuno Espírito Santo was named the new manager of Tottenham,[341] but was replaced by Antonio Conte in early November after only four months in charge, the shortest tenure as permanent manager in the club's history since Santini.[342][343] Despite an early exit in the Conference League, Conte guided Spurs to fourth and back to a Champions League spot at the end of the 2021–22 season, after two seasons out of the European competition.[344] Conte left on 26 March 2023 following his criticism of the players and the club, and his assistant Cristian Stellini then served as the acting head coach,[345] followed again by Ryan Mason.[346]

Ange Postecoglou was appointed the manager of Tottenham in June 2023.[347] Postecoglou started the first 10 games of the 2023–24 season unbeaten with 8 wins and 2 draws, which is Tottenham's best start in a top-flight season since 1960–61.[348] Postecoglou led the team to qualification for the 2024-25 UEFA Europa League after finishing fifth in the league.[349]

See also

[edit]- List of Tottenham Hotspur F.C. records and statistics

- List of Tottenham Hotspur F.C. players

- List of Tottenham Hotspur F.C. managers

Notes

[edit]- ^ For an example of clubs called Spurs, see report of a match in The Referee, 14 November 1880, page 6

References

[edit]- ^ a b c The Tottenham & Edmonton Herald 1921, p. 4.

- ^ a b Cloake & Fisher 2016, Chapter 1: A crowd walked across the muddy fields to watch the Hotspur play.

- ^ a b Welch 2019, p. 20.

- ^ Donovan 2017, p. 39.

- ^ The Tottenham & Edmonton Herald 1921, p. 5.

- ^ "John Ripsher". Tottenham Hotspur Football Club. 24 September 2007. Archived from the original on 30 June 2018. Retrieved 29 May 2017.

- ^ Spencer, Nicholas (24 September 2007). "Why Tottenham Hotspur owe it all to a pauper". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 9 May 2019. Retrieved 29 May 2017.

- ^ Welch 2019, p. 41.

- ^ Goodwin 1988, pp. 10–11.

- ^ "Northumberland Development Project, Tottenham". Haringey Council. October 2009. Retrieved 8 August 2019.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Campaigners say demolition of Tottenham Hotspur's club headquarters has "robbed" town of history". This is Local London. 16 June 2016. Archived from the original on 6 August 2017. Retrieved 5 August 2017.

- ^ Donovan 2017, p. 35.

- ^ Donald Insall Architects (April 2016). "The Red House, 748 Tottenham High Road". Haringey Council. Archived from the original on 16 June 2021. Retrieved 8 August 2019.