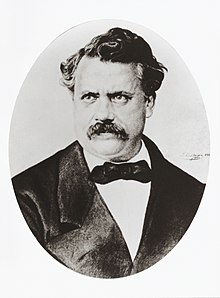

Louis Vuitton (designer)

Louis Vuitton | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 4 August 1821 Anchay, Jura, France |

| Died | 27 February 1892 (aged 70) Asnières-sur-Seine, France |

| Occupation | Malletier |

| Known for | The founder of Louis Vuitton |

| Spouse | Clemence-Emilie Parriaux |

| Children | Georges Ferréol Vuitton |

Louis Vuitton (French: [lwi vɥitɔ̃] ; 4 August 1821 – 27 February 1892)[1] was a French fashion designer and businessman. He was the founder of the Louis Vuitton brand of leather goods now owned by LVMH. Prior to this, he had been appointed as trunk-maker to Empress Eugénie de Montijo, wife of Napoleon III.[2]

Life and career

[edit]

Vuitton was born to a family of artisans, carpenters, and farmers. At the age of 10, his mother, a hat-maker, died, and his father followed soon after. Following a difficult relationship with his adoptive stepmother, Vuitton left his home in Jura (department), in Franche-Comté in the spring of 1835, at the age of 13. Taking odd jobs along the way, Vuitton traveled approximately 292 miles (470 km) to Paris. Arriving in 1837, in the middle of the Industrial Revolution, he apprenticed under Monsieur Marechal, a successful trunk maker and packer. Within a few years, Vuitton gained a reputation amongst Paris' more fashionable class as one of the city's premier practitioners of the craft.

After the reestablishment of the French Empire under Napoleon III, Vuitton was hired as a personal trunk maker and packer for the Empress of The French. She charged him with "packing the most beautiful clothes in a quite exquisite way." This provided Vuitton with a gateway to his other elite and royal clients who provided him with work for the rest of his career.

In 1854, at age 33, Vuitton married 16-year-old Clemence-Emilie Parriaux. Soon after, he left Marechal's shop and opened his own trunk making and packing workshop in Paris. Outside of his shop hung a sign that read: "Securely packs the most fragile objects. Specializing in packing fashions."[3] In 1858, inspired by H.J. Cave & Sons of London, Vuitton introduced his revolutionary rectangular canvas trunks at a time when the market had only rounded-top leather trunks. The demand for Vuitton's durable, lightweight designs spurred his expansion into a larger workshop in Asnières-sur-Seine. The original pattern of the shellac embedded canvas was named "Damier".

Vuitton also designed the world's first pick-proof lock. All lock patterns were safely kept at Vuitton's workrooms and registered with the owner's name in case another key was needed.

In 1871, as a result of the Franco-Prussian War, demand fell sharply, and Vuitton's workshop was in shambles. Many of his tools were stolen and his staff were gone. Vuitton rebuilt immediately, erecting a new shop at 1 Rue Scribe, next to a prestigious jockey club in the heart of Paris. In 1872, Vuitton introduced a new line, featuring beige monogrammed designs with a red stripe that would remain a signature of his brand long after he died in 1892 due to a severe and aggressive cancer in his brain (glioblastoma).[4]

Nazi Collaboration

[edit]During World War II, Louis Vuitton, had ties to the Vichy regime in Nazi-occupied France. Louis Vuitton was the only brand allowed to work along the ground floor on the Hotel du Parc in Vichy, which was serving its purpose as the headquarters for the Vichy government, led by Marshal Philippe Petain. The items that LV produced during this time were all items created for glorifying Petain. For example, more than 2,500 busts were created during this time for Petain. There were people from Louis Vuitton's family that was involved in this Nazi production too. Gaston Vuitton, the grandson of the founded, instructed his son to forge links with the Petain government to keep the business afloat and steady. Another family member, Henry Vuitton, was known to frequent a popular Gestapo Cafe, and was respected by the Petain government for his loyalty towards them. This type of behavior from the company was swept under the rug in order to protect the reputation of the company. However, in the early 2000's, when this information had reached public media, there was an outrage from the public. Although many people backlashed LV, the company did not face any long-term punishment.

References

[edit]- ^ "Timeline". Louis Vuitton. Archived from the original on 19 December 2008. Retrieved 3 March 2008.

- ^ De Luna, Alexis (1995). Contemporary fashion. London: St. James Press. p. 750. ISBN 1-55862-173-3.

- ^ "Louis Vuitton". Vogue. UK. 20 June 2012. Archived from the original on 14 August 2016. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- ^ "Diamond Portraits: Louis Vuitton". Ehud Laniado. Archived from the original on 8 August 2020. Retrieved 6 September 2018.