Otago Infantry Regiment (NZEF)

| Otago Infantry Regiment | |

|---|---|

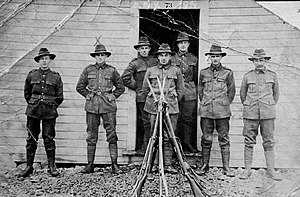

The Otago Infantry Regiment suffered a higher proportion of casualties than any other military unit at Passchendaele. These are the survivors of Walter Parker's company on 20 October 1917. | |

| Active | 1914–1919 |

| Country | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch | |

| Type | Infantry |

| Role | Light infantry |

| Size | Regiment |

| Part of | New Zealand and Australian Division, then from 1916 the New Zealand Division |

| Engagements | Egypt 1915–16, Gallipoli Campaign, France and Flanders 1916–18, Battle of the Somme, Battle of Messines (1917), Ypres 1917, Battle of Passchendaele, Battle of Bapaume 1918, Battle of Cambrai (1918)[1] |

| Commanders | |

| Regiment 1914–15 | Lieut.-Colonel T. W. M'Donald;[2] Major A. Moore |

| 1st Battalion 1916–1919 | Lieut. Colonel Charters; Major Hargest |

| 2nd Battalion 1916–1919 | Lieut. Colonel A. Moore; Major G. S. Smith;[3] Lieut. Colonel D. Colquhoun |

| 3rd Battalion 1916–1919 | Major D. Colquhoun; Lieut. Colonel G. Mitchell |

| Insignia | |

| Distinguishing Patch | |

The Otago Infantry Regiment (Otago Regiment) was a military unit that served within the New Zealand Expeditionary Force (NZEF) in World War I during the Gallipoli Campaign (1915) and on the Western Front (1916–1919).[4][5][6] This Regiment and the Otago Mounted Rifles Regiment were composed mostly of men from Otago and Southland.[7] The Otago Infantry Regiment represented the continuation of the Dunedin and Invercargill Militia Battalions formed in 1860.[8][9]

Preparation and first deployment

[edit]The Regiment was formed on 7 August 1914 with seven officers and up to 70 men starting their training at Dunedin's Tahuna Park.[10] This number was to quickly grow and 34 officers and 1,076 men landed in Egypt on 1 December later that same year.[5]

Some soldiers were never to see foreign deployment, instead being sent to the military hospital on Quarantine Island in Otago Harbour which dealt with cases of sexually transmitted disease.[11] These diseases were to be a continuing problem in Egypt and France. The safe sex advice from people like volunteer nurse and New Zealander Ettie Rout, was actively discouraged by the authorities until late in the war.[12]

After almost two months in Egypt on 26 January 1915 the Regiment was ordered north to Kubri, to help form a defensive line against an expect Ottoman Empire attack on the Suez Canal. The line was on the eastern side of the canal and extended between the Little Bitter Lake in the North and Suez in the South. Here they combined with the already stationed Indian troops. The attack came on 3 February and was repulsed, the Otago Infantry Regiment was kept in reserve.[13]

Gallipoli

[edit]The Regiment began preparing for the invasion of Gallipoli in early April 1915. Their training was focused on strength for the broken and steep terrain they would encounter. At this point the Regiment (then named the Otago Battalion) had four companies, 4th (Otago), 8th (Southland), 10th (North Otago) and 14th (South Otago).[14][15] On 10 April they departed Alexandria on the Annaberg, a captured enemy ship that was 'filthy beyond description, and abominably louse-ridden'. Three days later they arrived at Mudros in the Greek Islands, the staging area of the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force.[14]

The landing

[edit]

On 25 April between 2:30 and 4 p.m. the Otago Battalion troops disembarked from their boats at Gallipoli.[16] This was after a significant gap in the landings from the rest of the invasion which had occurred before 10 a.m. that morning. The Battalion was ordered first to cover the left flank and then to Plugge's Plateau where initial progress from the morning's landings had become bogged down. The Battalion was disorganized and was not incorporated into the broken front line as a single unit. Heavy fighting occurred until early the next morning. During this time several Ottoman counterattacks occurred but the Regiment held its ground, despite being without effective artillery support.[17]

The next morning brought a considerable Ottoman artillery barrage, which could now be returned by two New Zealand guns and supporting naval vessels. The 10th Company of the Battalion was sent to Steel's Post for two days of heavy fighting to aid the Australians already there. The evening of the second day was relatively quiet along the rest of the Otago Battalion line.[18] The invasion force had a secure beachhead, but had failed to reach their planned targets or capture the heights around the landing site.

A failed offensive

[edit]A limited offensive was instigated on 2 May to capture a ridge (later to be called Dead Man's Ridge) between Quinn's Post and Pope's Hill. It involved New Zealand and Australian troops, with the British in reserve. The Otago Battalion was to advance about 400 m along the ridge near Knoll 700, flanked by the Canterbury Battalion. The Otago Battalion was to lose about half its men as dead and wounded in the attack.[19]

On 26 October the 2nd Maori Contingent arrived at Suez from New Zealand adding 300 men to the Otago Infantry Regiment.[20]

France and Flanders

[edit]

The Otago Infantry Regiment was involved in fighting on the Western Front from 1916 to 1918.[22][23] Before moving to France the Regiment was reorganized and now comprised the 1st and 2nd battalions as part of the newly formed New Zealand Division. The 1st Battalion was part of the Division's 1st Infantry Brigade and the 2nd Battalion was part of the 2nd Infantry Brigade, effectively splitting the Otago Infantry Regiment in two.[24]

Lieut.-Colonel A. Moore who had senior commands, of and within, the Regiment since Egypt in 1914 was reassigned on 25 August 1916. He was later killed in action.[25]

Two soldiers from the Otago Regiment were executed: Jack Braithwaite in 1916 and Victor Spencer in 1917, charged with mutiny and desertion respectively. They were pardoned 93 years later.[26]

During early 1918 the 3rd Battalion from Otago supplied reinforcements to the two active Otago Battalions on the front.[27] Archibald Baxter an Otago conscientious objector was assigned to the 3rd Otago Battalion during early 1918.[28]

In June 1918 Cecil Alloo rose from the ranks in the Regiment to become the first commissioned officer of Chinese descent in New Zealand's armed forces.[29]

The Regiment last saw action on 5 November 1918.[30] The armistice was met with apathy by most of the men of the Regiment.[31]

Germany

[edit]Some in the Regiment expressed a wish to return to New Zealand when the war ended; however, the New Zealand Division was given occupation duties. On 28 November the Regiment advanced through Belgium towards Germany, on foot due to the damaged rail network. On 1 December, in Bavais, George V and Edward VIII (then Prince of Wales) attended a Church Service with members of the Regiment. They then continued their journey and reached the German border on 20 December 1918. Their final deployment was in Mulheim which they reached by train, boat and on foot. The attitude of the liberated French and Belgian populous was one of unmitigated enthusiasm, while the Germans were reserved, possibly afraid, but not openly hostile.[32]

The Regiment's main duties during the occupation of Germany were guarding war supplies and clearing mines. On 4 February 1919 due to thinning ranks as men were sent home, the Regiment was consolidated into a single Otago Battalion. The Otago Battalion was finally amalgamated into the South Island Battalion on 27 February. By the start of April the South Island Battalion had left Germany. The Otago Infantry Regiment was well represented one last time at a victory parade through London on 3 May and then returned home.[33]

Return to Otago and the Regiment's future

[edit]The men of the Regiment returned to Dunedin to a heroes welcome, greater social standing and numerous types of financial assistance. This was of considerable benefit to most of those who were physically or mentally healthy enough to take advantage of the opportunities.[31]

The Otago Infantry Regiment was reinstated as the Otago Regiment and the Southland Regiment, which existed intermittently between 1921 and 1948.[34] They did not see overseas service in World War II. However, later iterations of the Regiment would claim battle honours from the battalions of the 2nd Division that contained large numbers of Otago and Southland troops (23rd, 26th, 30th and 37th). The Otago and Southland regiments were amalgamated in 1948 to form the Otago Southland Regiment (renamed the 4th Otago and Southland Battalion Group in 1964).[8] As of this Battalion's amalgamation in 2012 no infantry unit has the Otago name.

Gallery

[edit]-

The Regiment's officers on the Annaberg

-

1st Battalion cooks

-

Typical French billet, 1916

-

Lieut. Colonel Moore

-

Non commissioned officers Otago Regiment

-

1st Battalion officers

-

2nd Battalion officers

-

3rd Battalion officers

-

Captured German tank

-

Makeshift regimental canteen near the Selle, 1917

See also

[edit]Related military units

[edit]- New Zealand Division

- New Zealand Expeditionary Force

- Otago Mounted Rifles Regiment

- Otago and Southland Regiment

War graves

[edit]- List of war cemeteries and memorials on the Gallipoli Peninsula

- List of Commonwealth War Graves Commission World War I memorials to the missing in Belgium and France

References

[edit]- ^ "Otago Infantry Regiment – Infantry units NZHistory, New Zealand history online". nzhistory.govt.nz. Retrieved 2019-01-17.

- ^ "Otago Daily Times, Issue 16202, 12 October 1914". paperspast.natlib.govt.nz. Retrieved 2019-01-16.

- ^ "Major G. S. Smith NZETC". nzetc.victoria.ac.nz. Retrieved 2019-01-16.

- ^ "Otago Infantry Regiment – Infantry units NZHistory, New Zealand history online". nzhistory.govt.nz. Retrieved 2019-01-15.

- ^ a b Byrne 1921, pp. 7–9.

- ^ Lewis, John (2018-04-26). "Daughter pieced together father's WW1 experience". Otago Daily Times Online News. Retrieved 2019-01-23.

- ^ Dungey, Kim (2010-09-09). "150 years of service". Otago Daily Times Online News. Retrieved 2019-01-16.

- ^ a b Phillips 2006, p. 86.

- ^ Date: 8-6-1920 (1920-08-06). "Otago Regiment (Otago Daily Times 8-6-1920)". natlib.govt.nz. Retrieved 2019-01-23.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Byrne 1921, pp. 5–6.

- ^ "Military Hospital 1915–1919 | Quarantine Island / Kamau Taurua". Retrieved 2019-01-17.

- ^ ToitÅ« Otago Settlers Museum (11 September 2014), Journey of the Otagos – Episode 8 – Behind the lines, archived from the original on 2021-12-21, retrieved 2019-01-17

- ^ Byrne 1921, pp. 12–13.

- ^ a b Byrne 1921, pp. 13–19.

- ^ Ferguson, David. "The History of the Canterbury Regiment, N.Z.E.F. 1914 - 1919". nzetc.victoria.ac.nz. Retrieved 2019-01-23.

- ^ "'Needless to say, we hung on…': The Otagos at Gallipoli | WW100 New Zealand". ww100.govt.nz. Retrieved 2019-01-16.

- ^ Byrne 1921, pp. 20–24.

- ^ Byrne 1921, pp. 24–25.

- ^ Byrne 1921, pp. 28–32.

- ^ "Maori Pioneer Battalion – World War One – Timeline". www.sooty.nz. Retrieved 2019-01-16.

- ^ Byrne 1921, pp. 317–320.

- ^ "Wrong place at the wrong time". Otago Daily Times Online News. 2017-10-07. Retrieved 2019-01-16.

- ^ "The Battle of the Somme, September 1916: survival and loss". Te Papa’s Blog. 2016-09-14. Retrieved 2019-01-16.

- ^ Byrne 1921, pp. 75–82.

- ^ Byrne 1921, pp. 109–110.

- ^ "The executed five Great War Story | NZHistory, New Zealand history online". nzhistory.govt.nz. Retrieved 2019-01-17.

- ^ Byrne 1921, pp. 261–261.

- ^ Baxter, Archibald (2005). We Will Not Cease. New Zealand Electronic Text Centre.

- ^ "The story of a unique WW1 soldier". Otago Daily Times Online News. 2018-04-27. Retrieved 2019-02-10.

- ^ Houlahan, Mike (2018-11-02). "One last battle left to fight". Otago Daily Times Online News. Retrieved 2019-01-15.

- ^ a b "Journey of the Otagos – Episode 11 – Coming Home (Toitū Otago Settlers Museum)". www.youtube.com. 2014. Archived from the original on 2021-12-21. Retrieved 2019-01-17.

- ^ Byrne 1921, pp. 385–387.

- ^ Byrne 1921, pp. 388–389.

- ^ "The Otago Regiment [New Zealand]". 2006-05-25. Archived from the original on 2006-05-25. Retrieved 2019-01-23.

Sources

[edit]- Byrne, A. E. (1921), Official History Of The Otago Regiment in The Great War 1914–1918, J. Wilkie & Company, p. 407, ISBN 9781843425694

- Phillips, Carol J. (2006). The Shape of New Zealand's Regimental System (MA). Massey University.

- Pryce, Jack (2017-10-06). Jack's Journey: A Soldier's Experience of the First World War. Glacier Press. ISBN 9780473407063.