Privy midden

The privy midden (also midden closet) was a toilet system that consisted of a privy (outhouse) associated with a midden (or middenstead, i.e. a dump for waste). They were widely used in rapidly expanding industrial cities such as Manchester in England, but were difficult to empty and clean. A typical comment was that they were of "most objectionable construction" and "usually wet and very foul".[1] They were replaced eventually by pail closets and flush toilets. Similar systems still exist in some developing countries, but the term "privy midden" is now an archaism.

Development and improvement

[edit]

The midden closet was a development of the privy, which had evolved from the primitive "fosse" ditch.[citation needed] The early version was essentially an outhouse for public use, located over a hole in the ground at a public dump.

In a speech given to the Institution of Civil Engineers in 1876 a Mr Redgrave described the midden closet as representing "the standard of all that is utterly wrong, constructed as it is of porous materials, and permitting free soakage of filth into the surrounding soil, capable of containing the entire dejections from a house, or from a block of houses, for months and even years".

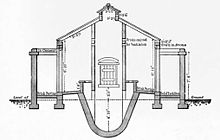

Later improvements, such as a midden closet built in Nottingham, used a brick-raised seat above a concave receptacle to direct excreta toward the centre of the pit—which was lined with cement to prevent leakage into the surrounding soil. This closet was also designed with a special opening through which deodorising material could be scattered over the top of the pit. A ventilation shaft was also installed. The design offered a significant improvement over the less advanced midden-privy, but the problems of emptying and cleaning such pits remained and thus the pail system, with its easily removable container, became more popular.[2]

Problems with middens

[edit]By 1869 Manchester had a population of about 354,000 people served by about 38,000 middensteads and 10,000 water closets. An investigation of the condition of the city's sewer network revealed that it was "choked up with an accumulation of solid filth, caused by overflow from the middens".[3] Such problems forced the city authorities to consider other methods of human waste disposal. The water closet was used in wealthy homes, but concerns over river pollution, costs and available water supplies meant that most towns and cities chose more labour-intensive dry conservancy systems.[4] Manchester was one such city and by 1877 its authorities had replaced about 40,000 middens with pail and midden closets, rising to 60,000 by 1881.[4] The soil surrounding the old middens was cleared out, connections with drains and sewers removed and dry closets erected over each site. A contemporary estimate stated that the installation of about 25,000 pail closets removed as much as 3,000,000 imperial gallons (14,000,000 L) of urine and accompanying faeces from the city's drains, sewers and rivers.[5]

The 1868 Rivers Pollution Commission reported two years later: "privies and ashpits are continually to be seen full to overflowing and as filthy as can be ... These middens are cleaned out whenever notice is given that they need it, probably once half-yearly on an average, by a staff of nightmen with their attendant carts."[6] (See Night soil.)

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ "An Illustrated History of Old Sutton in St.Helens Part 18 (of 53) – Health and Sanitary Conditions in Sutton". Archived from the original on 2011-07-30.

The privy-middens are of the most objectionable construction ...they are usually wet and very foul ... [excrement is] carried out by wheelbarrow or basket for some distance to the streets where the matter is often again deposited before its removal. This operation is performed by scavengers in the employ of the Corporation

- ^ Sutcliffe 1899, pp. 46–49

- ^ Power 1877, p. 1

- ^ a b Hassan 1988, p. 26

- ^ Power 1877, pp. 1–2

- ^ Sutcliffe 1899, pp. 45–46

Bibliography

[edit]- Hassan, John (1998), A history of water in modern England and Wales (illustrated ed.), Manchester: Manchester University Press ND, ISBN 0-7190-4308-5

- Power, W. A. (1877), The pail closet system: progress at Manchester, Manchester Selected Pamphlets, JSTOR 60237862

- Sutcliffe, G. Lister, ed. (1899), The principles and practice of modern house-construction, London: Blackie