Salamiyah

Salamiyah

سلمية | |

|---|---|

View of Salamiyah | |

| |

| Coordinates: 35°0′42.48″N 37°3′9″E / 35.0118000°N 37.05250°E | |

| Country | Syria |

| Governorate | Hama |

| District | Salamiyah |

| Subdistrict | Salamiyah |

| Control | |

| Settled | 3500 BCE |

| Elevation | 475 m (1,558 ft) |

| Population (2004 census) | |

• Total | 66,724 |

| • Ethnicities | Arab |

| • Religions | Ismailis and Alawites |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (EEST) |

| Area code | 33 |

Salamiyah (Arabic: سلمية, romanized: Salamiyya; also transliterated Salamiyya, Salamieh or Salamya) is a city in central Syria, administratively part of the Hama Governorate. It is located 33 kilometres (21 miles) southeast of Hama, 45 kilometres (28 miles) northeast of Homs.

The city is nicknamed the "mother of Cairo" because it was the birthplace of the second Fatimid caliph al-Qa'im bi-Amr Allah, whose dynasty would eventually establish the city of Cairo, and the early headquarters of his father Abdullah al-Mahdi Billah who founded the Fatimid Caliphate. The city is an important center of the Shi'ite Nizari Isma'ili and Taiyabi Isma'ili Islamic schools and also the birthplace of influential poet Muhammad al-Maghut. The population of the city is 66,724 (2004 census).[2]

Geography

[edit]Salamiyah lies in a fertile plain on the edge of the Syrian steppe,[3] 40 kilometers (25 mi) southeast of Hama and 51 kilometers (32 mi) northeast of Homs.[4] It is close to the al-A'la plateau to its north and has an average elevation of 1,500 feet (460 m) above sea level.[3]

History

[edit]Byzantine period

[edit]During the Byzantine period, the city was a flourishing town called Salaminias or Salamias.[3] It was well-integrated with the road networks connecting the villages between Emesa (Homs), Chalcis (Qinnasrin) and Resafa. Several Byzantine-era ruins attest to its regional importance, though the historian Elizabeth Kay Fowden asserts "little evidence remains to help reknit the town's history".[5] Its bishop Julian attended the consecration of Patriarch Severus of Antioch in 512,[5] indicating the town was a bishopric by that time.[6] One of the few dated inscriptions commemorates the construction of a church dedicated to Theotokos in 604.[5] An undated inscription credits the locals' patronage of the town's fortifications and honors St. Sergius, a popular saint amongst the Christian inhabitants of the Syrian steppe.[7]

Early Muslim period

[edit]Salamiyah was conquered by the Muslim Arabs in 636, during the Muslim conquest of Syria, and became part of Jund Hims (the military district of Homs) through the early Muslim period (7th–11th centuries). Not long after the rise of the Abbasid Caliphate in 750, Salamiya was settled by the Abbasid dynast Salih ibn Ali and his descendants. Salih was made governor of Syria and the Jazira in 758 and thereafter began the reconstruction of Salamiyah. His son Abdallah undertook significant reconstruction efforts there and built the irrigation networks of the town and the surrounding villages. Caliph al-Mahdi, Abdallah's cousin and brother-in-law, stayed in Salamiyah and admired his house there on his way to Jerusalem in 779–780 and appointed him governor of the Jazira. Abdallah's son Muhammad controlled the town in the early 9th century and made it a thriving commercial center. Two Abbasid inscriptions have been found in the town: a mosque foundation inscription likely dated to 767 and another mosque inscription likely dated to 893; otherwise no Abbasid remains in Salamiyah are extant.[3]

Around the early 9th century, Salamiyah became home to the great-grandson of Ja'far al-Sadiq, Abdallah, who concealed his identity and pretended to be a regular member and merchant of the Banu Hashim (the clan to which both the Abbasids and Alids belonged). He was allowed to stay in the town by Muhammad ibn Abdallah ibn Salih, the Abbasid governor, and built a palace there, which continued to be used by his descendants and successors as the leaders of the Isma'ili Shia da'wa. The Isma'ili leader Abdallah al-Mahdi Billah was born in Salamiyah in 873 or 874 and instituted reforms to the da'wa, leading to a break with Hamdan Qarmat, who thereafter headed the breakaway Qarmatian Isma'ili faction in Iraq and Bahrayn. The Qarmatian leader Zakarawayh ibn Mihrawayh led the Qarmatian revolts in Iraq and Syria (902–907). The Qarmatians razed Salamiyah in 903, massacring its inhabitants, though Abdallah al-Mahdi had left the city the year before and went on to establish the Fatimid Caliphate. The Abbasids suppressed the Qarmatian revolt near Salamiyah in late 903.[8]

Throughout the 10th century, Salamiyah was likely an abode for the nomadic Arab tribes of the Syrian Desert.[8] It was captured by the Fatimid general Ali ibn Ja'far ibn Fallah in 1009. Ali ibn Ja'far was the original builder of the mausoleum in Salamiyah dedicated to Abdallah (the descendant of Ja'far al-Sadiq).[9] In 1083 or 1084 the place was taken over by the Arab brigand Khalaf ibn Mula'ib, who had already been in possession of Homs and recognized Fatimid suzerainty.[8] An inscription dating to 1088 on the door beam of the former mausoleum credits Khalaf for rebuilding it.[9]

Seljuk, Ayyubid and Mamluk periods

[edit]In 1092 Khalaf lost his territories, including Salamiyah, to Tutush, the brother of the Seljuk sultan Malikshah, and after Tutush's death in 1095, to his son Ridwan. The town, which during this period was unfortified, remained administratively attached to Homs and was on several occasions used as a marshaling point by Muslim armies campaigning against the Crusader states and Byzantine Empire. The Seljuk atabeg and founder of the Zengid dynasty, Imad al-Din Zengi, mobilized his troops in Salamiyah for his campaign against the Byzantines at Shaizar in 1137–1138.[8]

The founder and first sultan of the Ayyubid dynasty, Saladin, took over Homs, Hama and Salamiyah from the Zengid emir Fakhr al-Din Za'afarani in 1174–1175. Homs and Salamiyah were granted to his cousin Muhammad ibn Shirkuh and remained in the latter's family until the death of its last Ayyubid emir al-Ashraf Musa in 1163. Thereafter, it was incorporated into the Mamluk empire which had conquered much of Ayyubid Syria in 1260. The Ayyubids of the Shirkuh line rebuilt the fortress of Shmemis on a nearby hilltop in the al-A'la plateau in 1229. The Mamluk army was defeated by the Mongols led by Ghazan at Salamiyah in 1299, which paved the way for the short-lived Mongol occupation of Damascus.[8]

Ottoman period

[edit]Salamiyah's importance continued to decline under early Ottoman rule, which began in 1517. Administratively, it was the center of a sanjak (district) in the Tripoli Eyalet.[10] It was a large ruin which, in the 16th–18th centuries, served as a stronghold for the Al Hayar (or Abu Risha) emirs of the Mawali tribe, who were recognized by the Ottoman authorities as the commanders of the Bedouin of the Syrian steppe.[11][10]

In 1625 the Abu Risha emir Mudlij gave refuge to Sulayman Sayfa (of the Sayfa family of Tripoli), who had been driven out of his fortress at Safita by the Druze emir Fakhr al-Din Ma'n, and the rebel Aslan ibn Ali Pasha. Upon orders from Hafiz Ahmed Pasha, Mudlij executed both men in Salamiyah.[12] In 1623, the chief of the Harfush emirs of Baalbek, Yunus al-Harfush, was imprisoned in Salamiyah by a Bedouin ally of Mudlij, Khalil ibn Ajaj, butwas released by the intercession of Fakhr al-Din.[13] By 1636, Salamiyah, along with Haditha and Anah were governed by Tarbush Abu Risha.[14]

The Mawali tribes were driven out of the Syrian steppe in the late 18th century by the invasion of the Hassana, a strictly nomadic tribe of the Anaza confederation from Najd; the Anaza tribes thereafter dominated the steppe. As late as the 1830s, when Syria was under Egyptian administration (1831–1841), Salamiyah and all of its surrounding villages were uninhabited ruins.[15] Toward the end of the Egyptian interregnum, Salamiyah was repopulated as part of a wider government effort to resettle and recultivate the Syrian desert fringe, but was abandoned again soon after Egyptian forces withdrew from the region.[16]

Establishment as Isma'ili center

[edit]In July 1849, Isma'il ibn Muhammad, the Isma'ili emir of Qadmus in Syria's Jabal Ansariya coastal mountain range, obtained a firman from Sultan Abdülmecid I granting him permission to settle Salamiyah and its environs with his followers. This came as part of an agreement ending Isma'il's rebellion in the Khawabi valley at that time.[17] The Isma'ili settlers were initially exempted from taxes and conscription.[18] Many dwelt in the Shmeimis fortress while they developed the new settlement at Salamiyah,[19] which they named Mecidabad (Mejidabad) after the sultan; the original name eventually regained currency.[20]

Thereafter, significant migrations of Isma'ilis from Jabal Ansariya to Salamiyah followed,[21] the new arrivals drawn to the area by higher prospects of prosperity than in the coastal mountains, taxation and conscription exemptions, and the medieval connections with their faith.[22] Under Emir Isma'il's leadership, the community held off the Mawali, whose tribal territory they had encroached upon, and formed a loose alliance with the Sba'a, a Bedouin tribe of the Anaza confederation, which aided the Isma'ilis in their occasional conflicts with other Bedouin of the region.[21] By 1861, Salamiyah was recorded as a large village with considerable dwellings inside of its restored fortress. The growing number of Isma'ili emigrants began to branch out to the long-abandoned villages in Salamiyah's orbit and recultivated its fertile lands.[20][21] In settling the surrounding countryside, the Isma'ilis were gradually joined by Circassian refugees, who arrived in Syria in 1878, Alawites, and local semi-nomadic Bedouins,[20] though the lands of Salamiyah and its surroundings largely remained under Isma'ili ownership.[18]

In 1884, under Sultan Abdülmecid II, Salamiyah and its environs were made a kaza of Hama and its residents were subject to taxation and conscription. Within a few years, a permanent garrison was established there. By the close of the 19th century, Salamiyah, with its 6,000-strong population, was the largest Isma'ili center in the Ottoman Empire, and had a well-developed irrigation network. The community in Salamiyah shifted their religious allegiance to the Qasim-Shahi line of imams, by then led by the India-based Aga Khan III, while most of their counterparts in the Jabal Ansariya kept to the Mu'min-Shahi line of imams. The Aga Khan invested considerably in Salamiyah, building several schools and an agricultural institution there.[18]

Post-Syrian independence

[edit]Salamieh is currently the largest population center of Isma'ili Muslims in the Arab world. The remains of Prince Aly Khan, the father of the current Nizari Isma'ili Imam Aga Khan IV, are buried in the city. The headquarters of the Isma'ili Shia Higher Council of Syria are in the city, as are dozens of Jama'at Khana. During the mid-twentieth century, Salamieh saw a growth of religious diversity with the building of the first Sunni mosque, and now the city is home to almost a dozen Sunni mosques and a Ja'fari Shia mosque in the city's Qadmusite Quarter which is home to most of the city's Ithna Ashari Shia which migrated to the city after ethnic and religious clashes in their hometown of Qadmus in the early twentieth century. Currently, a little more than half of the city's residents are Isma'ili.[23]

In 1934, Muhammad al-Maghut, the poet credit for being the father of free verse Arab poetry, was born in Salamieh. In 1991, visitors from the Dawoodi Bohra sect of Isma'ili Shia Islam in Yemen built the Mosque of Imam Isma'il adjacent to the grave of the Isma'ili Imam Isma'il. The mosque was built by order of their leader the Da'i al-Mutlaq Mohammed Burhanuddin according to an inscription on the mosque's wall. Although currently used for worship by Sunni Muslims, the mosque and mausoleum are visited in religious pilgrimages by Dawoodi Bohra worldwide.

Salamieh is located at the crossroads

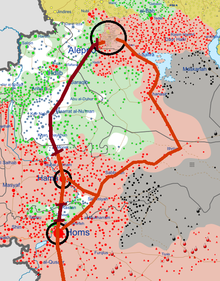

From 2012 to 2017, with the development of frontlines in Syrian Civil War, the city grew in its strategic importance. With Al-Rastan becoming a pocket outside government control along the Homs-Hama Motorway, and the developments in Idlib governorate resulting in the government also losing control of large segments of the main Hama-Aleppo Highway, the Homs-Salamieh, Hama-Salamieh, and Salamieh-Ithriya-Aleppo roads became major lines connecting these government-held areas. This importance was why the town was the target of occasional ISIL or rebel mortar attacks. Also, some of the town's citizens have participated in protests during the Civil War.[24] The importance of Salamieh diminished following the Syrian Army's securing of the Homs-Hama Motorway on February 1, 2018, during the Northwestern Syria campaign.

Residence history of Salamieh

[edit]The residence history of Salamieh is as follows:[25]

"The Ismaili dais in search of a new residence for their Imam came to Salamia and inspected the town and approached the owner, Muhammad bin Abdullah bin Saleh, who had transformed the town into a flourishing commercial centre. They told him that there was a Hashimite merchant from Basra who was desirous of settling in the town. He readily accepted and pointed out to them a site along the main street in the market, where existed a house belonging to a certain Abu Farha. The Ismaili dais bought it for their Imam and informed him about it. Wafi Ahmad arrived to his new residence as an ordinary merchant. He soon pulled down the old building and had new ones built in its place; and also built a new wall around it. He also built a tunnel inside his house, leading to the desert, whose length was about 12 miles (19 kilometres). Money and treasures were carried on camels to the door of that tunnel at night. The door opened and the camels entered with their loads inside the house."

The photo placed here shows the mausoleum of the Imam. Near his qabr mubarak ("blessed grave"), the tunnel opening still exists.

Culture

[edit]The city is an agricultural center, with a largely agriculture based economy. Mate is extremely popular in Salamieh and a drink of major cultural importance in social gatherings.

Main sights

[edit]- A hammam of unique architecture, likely dating from the Ayyubid era, sits in the town center, near a large underground Byzantine cistern which is said to lead all the way to Shmemis castle. There also exists one wall from an ancient Byzantine citadel.

- The castle, of Roman-Greek origins.

- Walls, rebuilt by Zengi

- Mosque of al-Imam Isma'il, which originated as an Ancient Greek temple of Zeus, and was turned into a church in Byzantine times.

- Remains of Roman canals, used for agriculture

Climate

[edit]Salamieh has a cold semi-arid climate (Köppen climate classification BSk).

| Climate data for Salamiyah (1991–2020) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 11.8 (53.2) |

13.9 (57.0) |

18.2 (64.8) |

23.6 (74.5) |

29.6 (85.3) |

33.9 (93.0) |

36.4 (97.5) |

36.6 (97.9) |

33.7 (92.7) |

28.4 (83.1) |

20.0 (68.0) |

13.4 (56.1) |

25.0 (77.0) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 2.2 (36.0) |

3.0 (37.4) |

5.5 (41.9) |

8.8 (47.8) |

13.3 (55.9) |

17.3 (63.1) |

19.9 (67.8) |

20.3 (68.5) |

17.6 (63.7) |

13.2 (55.8) |

6.8 (44.2) |

3.3 (37.9) |

10.9 (51.6) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 59.8 (2.35) |

49.8 (1.96) |

41.5 (1.63) |

20.4 (0.80) |

13.6 (0.54) |

1.7 (0.07) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.3 (0.01) |

3.4 (0.13) |

15.5 (0.61) |

30.3 (1.19) |

49.3 (1.94) |

290.3 (11.43) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1 mm) | 9.7 | 8.1 | 6.4 | 3.8 | 2.1 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.6 | 2.8 | 5.0 | 7.5 | 46.2 |

| Source: NOAA[26] | |||||||||||||

References

[edit]- ^ "After capturing strategic positions around Hama city | HTS takes control of Salamiyah city without fighting". SOHR. 5 December 2024. Retrieved 5 December 2024.

- ^ Salamyah city population Archived 2013-01-13 at archive.today

- ^ a b c d Kramers & Daftary 1995, p. 921.

- ^ Sharon 2007, p. 158.

- ^ a b c Fowden 1999, p. 113.

- ^ Honigmann 1947, p. 157.

- ^ Fowden 1999, pp. 112–113.

- ^ a b c d e Kramers & Daftary 1995, p. 922.

- ^ a b Sharon 2007, p. 161.

- ^ a b Winter 2019.

- ^ Douwes 2000, pp. 17–18, 26.

- ^ Abu-Husayn 1985, pp. 55–56, note 109.

- ^ Abu-Husayn 1985, p. 150.

- ^ Abu-Husayn 1985, p. 58, note 113.

- ^ Douwes & Lewis 1992, p. 274.

- ^ Douwes 2000, pp. 208–209.

- ^ Lewis 1952, pp. 70–71.

- ^ a b c Kramers & Daftary 1995, p. 923.

- ^ Bylinski 2006, p. 244.

- ^ a b c Tachjian 2017, p. 63.

- ^ a b c Lewis 1952, p. 72.

- ^ Douwes 2010, p. 492.

- ^ Syria's diverse minorities, BBC, 9 December 2011

- ^ "Syria Snapshot II: A Homecoming Trip to Salamiyeh | Al Akhbar English". Archived from the original on 2016-06-03.

- ^ "Wafi Ahmad in Salamia". www.ismaili.net. Retrieved February 8, 2024.

- ^ "Salamya Climate Normals 1991–2020". World Meteorological Organization Climatological Standard Normals (1991–2020). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on 2 September 2023. Retrieved 2 September 2023.

Bibliography

[edit]- Abu-Husayn, Abdul-Rahim (1985). Provincial Leaderships in Syria, 1575–1650. Beirut: American University of Beirut. ISBN 9780815660729.

- Bylinski, J. (2006). "Exploratory Mission to Shumaymis". In Kennedy, Hugh N. (ed.). Muslim Military Architecture in Greater Syria: From the Coming of Islam to the Ottoman Period. Leiden: Brill. pp. 243–250. ISBN 90-04-14713-6.

- Douwes, Dick (2000). The Ottomans in Syria: A History of Justice and Oppression. I.B. Tauris. ISBN 1860640311.

- Douwes, Dick (2010). "Migration, Faith and Community: Extra-Local Linkages in Coastal Syria". In Sluglett, Peter; Weber, Stefan (eds.). Syria and Bilad Al-Sham Under Ottoman Rule: Essays in Honour of Abdul Karim Rafeq. Leiden: Brill. pp. 483–498. ISBN 978-90-04-18193-9.

- Fowden, Elizabeth Kay (1999). The Barbarian Plain: Saint Sergius Between Rome and Iran. Berkely and Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-21685-3.

- Honigmann, Ernest (1947). "The Patriarchate of Antioch: A Revision of Le Quien and the Notitia Antiochena". Traditio. 5: 135–161.

- Kramers, J. H. & Daftary, Farhad (1995). "Salamiyya". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W. P. & Lecomte, G. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume VIII: Ned–Sam. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 921–923. ISBN 978-90-04-09834-3.

- Lewis, Norman N. (1952). "The Isma'ilis of Syria Today". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. 39: 69–77.

- Le Strange, G. (1890). Palestine Under the Moslems: A Description of Syria and the Holy Land from A.D. 650 to 1500. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Sharon, M. (2007). Corpus Inscriptionum Arabicarum Palaestinae, Addendum. BRILL. ISBN 978-9004157804.

- Winter, Stefan (2019). "Alep et l'émirat du désert (çöl beyligi) au XVIIe-XVIIIe siècle". In Winter, Stefan; Ade, Mafalda (eds.). Aleppo and its Hinterland in the Ottoman Period / Alep et sa province à l'époque ottomane. Brill. pp. 86–108. ISBN 978-90-04-37902-2.

- Tachjian, Vahe (2017). Daily Life in the Abyss: Genocide Diaries, 1915-1918. New York and Oxford: Berghahn. ISBN 978-1-78533-494-8.

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to Salamiyah at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Salamiyah at Wikimedia Commons