The House of Bijapur

| The House of Bijapur | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | Chand Muhammad and Kamal Muhammad |

| Year | circa 1680 |

| Medium | Ink, opaque watercolor, gold, and silver on paper |

| Dimensions | 41.3 cm × 31.1 cm (16.3 in × 12.2 in)[1] |

| Location | Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City |

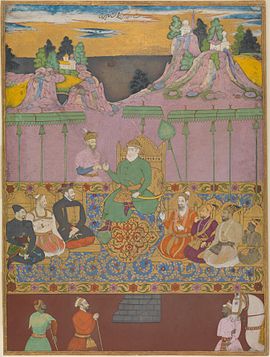

The House of Bijapur is a 17th-century Deccan-style painting, commissioned during the reign of the Bijapur Sultanate. It is currently housed in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City.[2]

The painting was probably a royal commission, from the reign of Sikandar Adil Shah, the final sultan of the Adil Shahi dynasty. It depicts eight rulers of the dynasty, with the founder Yusuf Adil Khan in the center, being handed a key of legitimacy. All the other monarchs surround him, each seated on a throne. This depiction of a multi-generational sequence of rulers is inspired from Mughal art. The style of the painting, however, is local, with a color palette and motifs characteristic of Deccan painting.[1]

It is considered to be an important example of the Bijapur school of Deccan art, since it is one of the last works of the school.

Significance

[edit]The details of the painting's provenance are not known. However, scholars suppose that it was a royal commission based on its scale, the subject matter, and the use of expensive colors. It was presumably commissioned for the court of Sikandar Adil Shah, and may have been a page taken from an album.[1][3]

The House of Bijapur is of a larger size than most manuscript pictures, measuring sixteen by thirteen inches. It is also significant due to its subject matter, as no other surviving Bijapur paintings portray the dynasty's members together, from the founder to the last ruler. Genealogical paintings of this sort, emphasizing the rulers' lineage, are known in Mughal art, and one of the most famous examples of this is the Princes of the House of Timur in the British Museum.[4]

The painting is one of the last works of the Bijapur school of miniature painting, representing the final phase of the style. It is dated to about 1680, and the Bijapur sultanate was conquered by the Mughals in 1686. Stuart Cary Welch thus describes the work as "a painted curtain call", as in, the last appearance of a group of actors to receive an ovation, before the play ended.[4]

Style

[edit]

The motivation behind such multi-generational depictions, common in Mughal art, was to symbolize the legitimacy of the rulers.[1] The layout of The House of Bijapur seems to be taken from a painting by Govardhan dated to about 1630-1640, depicting Babur receiving the imperial crown from his ancestor Timur, as Humayun looks on.[5] The careful modeling of the faces is also influenced by Mughal portraiture.[6]

While directly inspired from Mughal art, the artists have deliberately incorporated traditional elements of the Bijapur school in the painting. This is seen in the choice of the color palette, rich in lavender-pink, and distinctive shades of green, deep orange, and gold. The mountains in the background are of Safavid inspiration. The shifts in scale and perspective, sometimes illogical, such as the stairs leading up to the carpet without any support, are meant to convey an otherworldly mood.[7]

This deliberate use of Bijapuri and Safavid elements, while the subject itself is taken from Mughal art, shows the intent of the artists, to depict the Adil Shahi rulers as distinct from, but equal in stature to, their Mughal counterparts.[8]

Description

[edit]The painting can be divided into four registers. The first register forms the background. The second and third registers depict the principal subject, that is, the Adil Shahi dynasty. The fourth register constitutes the base, where three attendants and a horse are pictured.[5][1]

Background

[edit]

The background is composed of distant pink hills, upon which are trees and white palaces. The hilltops pierce a golden sky, where white and blue clouds can be seen. The hills, palaces, and golden sky, are all common elements of Bijapur art.[9]

Beyond the hilltops, the ocean is depicted. Some scholars are of the opinion that this alludes to the short period of time the Adil Shahis controlled the Goan coast, thus representing the kingdom at its zenith. The slice of ocean also functions as an arrow, subtly pointing down towards the central figure of the painting, the dynastic patriarch Yusuf Adil Shah.[7][9]

Principal subject

[edit]The two middle registers depict the principal subject. The painting portrays eight of the nine rulers of the Bijapur Sultanate, leaving out only Mallu Adil Khan, whose reign lasted for only seven months.[10] Each king is seated on a throne, the throne of the dynastic patriarch being the most elaborate.[1] The thrones are placed upon a blue and gold floral carpet, from which rise flat ceremonial umbrellas. The style of the carpet and the umbrellas is also local to the Deccan.[11]

In the group at the left are (from left to right) Ibrahim I, Ali I, and Ismail. Ibrahim I is portrayed in a white and gold robe, and a tight turban. The second figure, Ali I is depicted in full battle armor, in a nod to his victory at the battle of Talikota. Ismail is shown wearing a twelve-pointed cap (a reference to the twelve Imams of Shia Islam). He was a devout Shia, and during his reign, he had mandated the wearing of this cap for his soldiers.[12]

At the center is Yusuf Adil Khan, the progenitor of the dynasty. He is dressed in a green robe, the color symbolizing spiritual authority, and seated on a gilded throne, with a golden key in his right hand, a sword in his left, and with his right foot atop a globe. The key as well as the globe are motifs borrowed from Mughal paintings, used to symbolize the authority of the emperor.[13]

At his right side is a standing figure, appearing to have just given the key to Yusuf. This person, dressed in pink and appearing to emerge from the pink background, is wearing a Safavid style turban. It is identified to be Shah Abbas in an inscription. However, scholars including Zebrowski assert that this inscription is a later, erroneous addition, and that the figure is likely Shah Ismail or Safi-ad-Din Ardabili.[14]

In the group at the right are (from left to right) Ibrahim II, Muhammad, Ali II, and Sikandar. This group wear push daggers in their belts, as compared to the hilted daggers worn by the earlier rulers, in the group at the left. Ibrahim II is shown as pale-skinned, with an elongated face, and wearing a bejeweled turban characteristic of the time period of his reign. He is wearing strands of pearls, and holding a mango in his left hand. Muhammad is depicted with a Mughal-styled sash, typical to the time period of his reign. Ali II is depicted with red-stained lips. The final ruler, at the right edge, is Sikandar. He is depicted as a dark-skinned child of about ten to twelve years of age.[15][11][16]

The names of the artists, Kamal Muhammad and Chand Muhammad, are given in an inscription on the left in the Naskh script.[7]

Base

[edit]At the base of the painting are two attendants resting their hands on a staff on the left, and a groom with a horse on the right, with a small staircase in the middle. B. N. Goswamy notes that a horse with a groom is to be interpreted as a sign of a recent arrival, and that perhaps here it symbolizes the arrival of the young sultan Sikandar to the group of Adil Shahi monarchs.[1]

Derivative works

[edit]

A smaller iteration of this painting, in the Golconda school was among the fifty-five paintings collected by Niccolao Manucci.[11][17]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g Goswamy, B. N. (2014-12-01). The Spirit of Indian Painting: Close Encounters with 100 Great Works 1100-1900. Penguin UK. ISBN 978-93-5118-862-9.

- ^ Painting by Kamal Muhammad (active 1680s); Painting by Chand Muhammad (Indian, active 1680s) (1680), The House of Bijapur, retrieved 2024-12-06

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Hutton 2016, p. 11.

- ^ a b Hutton 2016, p. 1.

- ^ a b Hutton 2016, p. 3.

- ^ Kossak, Steven (1997). Indian Court Painting, 16th-19th Century. Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-87099-782-2.

- ^ a b c Ekhtiar, Maryam (2011). Masterpieces from the Department of Islamic Art in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 380. ISBN 978-1-58839-434-7.

- ^ Hutton 2016, p. 4.

- ^ a b Hutton 2016, p. 6.

- ^ Zebrowski 1983, p. 152.

- ^ a b c Haidar, Navina Najat; Sardar, Marika (2015-04-13). Sultans of Deccan India, 1500–1700: Opulence and Fantasy. Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 154. ISBN 978-0-300-21110-8.

- ^ Hutton 2016, p. 8-9.

- ^ Hutton 2016, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Zebrowski 1983, p. 150.

- ^ Michell, George; Zebrowski, Mark (2008-03-28). Architecture and Art of the Deccan Sultanates. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-05343-3.

- ^ Hutton 2016, p. 6-8.

- ^ Hutton 2016, p. 11-15.

Bibliography

[edit]- Zebrowski, Mark (1983). Deccani painting.

- Hutton, Deborah (2016). "Memory and Monarchy: A Seventeenth-Century Painting from Bijapur and its Afterlives". South Asian Studies. 32 (1): 22–41. doi:10.1080/02666030.2016.1179433. ISSN 0266-6030.