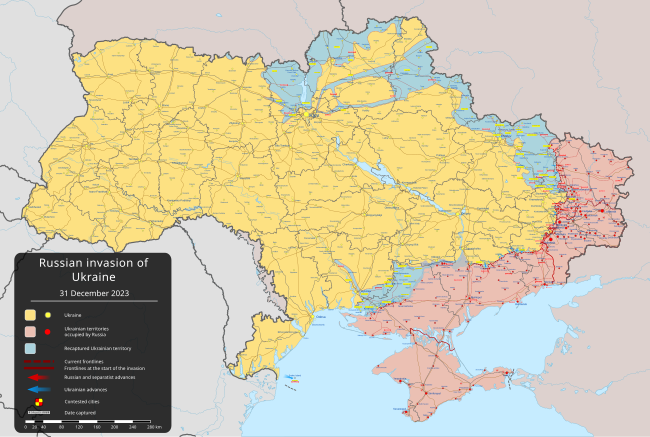

2023 Ukrainian counteroffensive

In early June 2023, during the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Ukraine launched a counteroffensive against Russian forces occupying its territory with a goal of breaching the front lines.[38][39][40][41][42] Efforts were made in many directions, primarily in Donetsk and Zaporizhzhia oblasts. In total, Ukraine recaptured 14 villages in Donetsk and Zaporizhzhia oblasts, with a total pre-war population of around 5,000. The counteroffensive was widely regarded as a crucial moment in the war.[43]

Planning for a major Ukrainian counteroffensive had begun as early as February 2023, with the original intention being to launch it in the spring.[44] However, various factors, including weather and late weapon deliveries to Ukraine, delayed it to summer, as it had not been deemed safe to progress.[45][46][47] Russia had begun preparing for the counteroffensive since November 2022 and had created extensive defensive infrastructure, including ditches, trenches, artillery positions, and landmines intended to slow the counteroffensive.[48][49][50] Ukraine met well-established Russian defenses in the early days of the counteroffensive and after that slowed their pacing in order to assess the extent of Russian defenses, demine territory, save troops, and exhaust Russia's military resources.[51] They made incremental gains by capturing over 370 km2 of territory, less than half of what Russia captured in all of 2023.[52]

Almost five months after its start, prominent Ukrainian figures and Western analysts began giving negative assessments of the counteroffensive; statements by Ukrainian general Valerii Zaluzhnyi in early November 2023 that the war was a "stalemate" were seen by observers as an admission of failure.[53] Rigorous assessments made by analysts followed, especially with regard to operational success, from several weeks earlier.[54] That same month, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy stated the war would be entering a new phase.[55] Ukrainian forces did not reach the city of Tokmak, described as a "minimum goal" by Ukrainian general Oleksandr Tarnavskyi,[56] and the probable initial objective of reaching the Sea of Azov to split the Russian forces in southern Ukraine remained unfulfilled.[57][58][6] By early December 2023, the counteroffensive was generally considered to be stalled or failed by multiple international media outlets.[59][60][61][62][63][5]

Background

State of the war

Following the Kherson and Kharkiv counteroffensives in late 2022, fighting on the front lines largely stagnated, with fighting mostly concentrated around the city of Bakhmut during the first half of 2023.[64]

Russian defenses

Russian fortifications in Ukraine had been described as the most "extensive defensive works in Europe since World War II" by the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS).[65] Construction to create military infrastructure had begun as early as November 2022 in order to entrench Russian troops into Ukrainian territory.[48] By April 2023, Russia built an 800 km (500 mi) long defense line in preparation for a Ukrainian counteroffensive.[66] The final lines of fortifications established by Russia prior to the counteroffensive amounted to being nearly 2,000 km (1,200 mi) long, extending from the border with Belarus to the Dnieper delta. Defenses primarily consisted of ditches, dragon's teeth, trenches, artillery positions, anti-vehicle barriers, and prepared firing positions for vehicles.[67] Russia had also created extensive minefield regions across the frontline regions with anti-tank mines. An estimated 170,000 km2 (66,000 sq mi) of territory had been mined, which also included Ukrainian mines laid in the Donbas region during the War in Donbas.[50] In early May, Russian forces had constructed a dam and moat around the captured city of Tokmak which is located near the frontline of the counteroffensive.[68]

In Zaporizhzhia Oblast, Russia constructed roughly three lines of defense: a 150 km (93 mi) long frontline from Vasylivka to Novopetrykivka on the Zaporizhzhia–Donetsk oblasts border, a 130 km (81 mi) long second line of defense from Orlynske to just north of Kamianka, and "a constellation of disconnected fortifications surrounding larger towns". The first line contains multiple counter-mobility barriers and infantry trenches backed by artillery positions located 30 km (19 mi) nearby. The second line is similar to the first, allowing Russia to set up a new front while also offering protection against flank attacks. The third line contains strategically positioned fortifications meant to serve as a contingency to preserve Russian positions in case of a Ukrainian victory.[69] It is predicted to be the most heavily fortified frontline region.[48] In Kherson Oblast, defenses were created in order to protect Crimea and the Dnieper, while trenches in the road are located every few kilometers. The purpose was to prevent amphibious warfare.[70] In Donetsk Oblast, Russian forces constructed field fortifications 5 km (3.1 mi) apart, combined with the urban terrain. Approximately 76% of the fortifications observed were estimated to have been created pre-2022, with the quality of them being doubted due to relative disuse over time. These fortifications center around Olhynka, Donetsk, Makiivka, and Horlivka.[71]

Prelude

Planning

By February 2023, Ukrainian and Western officials began discussing plans for a potential spring counteroffensive, while Ukrainian troops were receiving military training from NATO and anticipating Western equipment, primarily M1 Abrams and Leopard 2 tanks.[44] Ukraine had also formed multiple new units in early 2023.[72] Originally these were all supposed to be equipped with Western supplied weaponry, but some units, like the 31st Mechanized Brigade and the 32nd Mechanized Brigade, were equipped with older weapons such as the AKM assault rifle and the T-64 tank.[73][74] Another factor that had caused the counteroffensive to be delayed was the 2022–2023 Pentagon document leaks, in which sensitive US intelligence regarding the Ukrainian military was leaked by April, causing Ukraine to alter some of their military plans as a result. However, Ukrainian officials have disregarded the leaks and stated that they were still planning for the counteroffensive.[75][76] Despite this, American officials projected the counteroffensive to begin by May.[77] Ukraine began finishing preparations for an anticipated counteroffensive and would not explicitly announce when the counteroffensive would begin by May.[78]

Despite the general expectation that the counteroffensive would take place in spring, it did not. Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy explained that Ukraine had not received sufficient Western supplies and that Ukrainian military training from the West had not been completed yet. By May, Zelenskyy had not deemed the counteroffensive to be ready to start, as the delivery of Western weapons had caused a delay;[45][46] Zelenskyy had desired to start the counteroffensive "much earlier" and said that the delays had provided Russia with the opportunity to fortify their occupied territories.[47] Furthermore, weather was a substantial factor delaying the counteroffensive; during that time period, Ukraine was undergoing its rasputitsa (muddy season), making travel difficult for vehicles such as tanks.[45]

Shaping operations

In the months before the start of the counteroffensive, Ukrainian forces engaged in "shaping operations" to test Russian defenses and weaken logistics and supply chains deep inside Russian-occupied territories.[79][80] According to Western media, Ukrainian forces had built up an estimated 50,000 to 60,000 soldiers for the counteroffensive, organized into twelve brigades.[81][82][76] Three of these were trained in Ukraine, and the other nine were trained and equipped by the United States.[76][82]

Beginning in May 2023, Ukrainian forces engaged in "localized" counterattacks on the flanks of Bakhmut, as part of the larger battle in the city.[83] On 12 May Ukrainian forces forced the Russians out of the southern bank of the Berkhivske Reservoir, about 4 kilometres (2.5 mi) northwest of Bakhmut,[83] and claimed further gains of 20 square kilometres (7.7 sq mi) in the north and southern suburbs of Bakhmut later in the month.[84][85] Another large-scale Ukrainian counterattack operation began in and around Bakhmut on 5 June, when it was reported that Ukrainian forces had retaken part of the village of Berkhivka, north of Bakhmut.[86] Ukrainian forces claimed to have advanced hundreds of meters in multiple areas around Bakhmut's flanks throughout early June.[87][88][89]

On the Zaporizhzhia front, starting on 3 June, the Ukrainian 37th Marine Brigade engaged in a slow but consistent offensive action around the frontline settlement of Novodonetske in the Donetsk Oblast. Without armored support, the marines were able to push back the Vostok Battalion of the DNR's people's militia mostly through the use of artillery. The Ukrainian advance was further aided by the use of armoured personnel carriers (APCs) to rapidly transport marines to the front, and then withdrawing out of Russian artillery range.[90] Also on 3 June 2023, Zelenskyy stated that Ukraine was ready to launch a counteroffensive.[91] The next day, Ukrainian officials declared an "operational silence" to avoid compromising military operations.[92]

Counteroffensive

Start date

The exact launch date of the counteroffensive is debated, with conflicting information coming from various official sources. Russia claimed to have thwarted a "large-scale offensive" on 4 June,[1] and regarded that date as the start of Ukraine's counteroffensive.[93] On 5 June, Ukraine's Deputy Minister of Defense, Hanna Maliar, said that Ukrainian troops were "carrying out offensive actions" in several directions; earlier on, she and other officials had posted a social media video which carried the message that Ukraine would not announce the beginning of the counteroffensive.[3] The Ukraine defence ministry posted a video containing as a caption the words, "Plans love silence. There will be no announcement of the beginning."[3][94]

The Institute for the Study of War (ISW), an American think tank and war observer, reported that Ukraine had launched "wider counteroffensive operations" beginning 4 June.[2] Western media reported on 8 June that the counteroffensive had begun,[95][39] however on 15 June Mykhailo Podolyak, advisor to the Office of the President of Ukraine, stated the counteroffensive had not begun.[96] This claim would be reiterated by Maliar on 20 June.[97]

Southern front

In the southern region of Zaporizhzhia, Ukraine pursued two main vectors of attack: one in western parts of Zaporizhzhia, aiming towards the strategic Russian-occupied city of Melitopol, and the other in eastern parts of Zaporizhzhia, aiming towards Berdiansk on the coast of the Azov Sea.[98] Ukrainian general Oleksandr Tarnavskyi led the southern effort of the counteroffensive for Ukraine.[99]

Melitopol direction

On the morning of 4 June 2023, Russia reported Ukraine had begun a major offensive in five areas of the frontline in southern Donetsk Oblast.[1] The Institute for the Study of War also reported that Ukraine had launched operations as part of "wide counteroffensive efforts".[2] The following day, Ukraine confirmed an offensive was "taking place in several directions".[3]

On 8 June, Ukrainian forces launched counterattacks around the city of Orikhiv,[95][100] in the Polohy Raion of Zaporizhzhia Oblast, where Russian forces had constructed the Mala Tokmachka–Polohy defensive line. The attacks focused on the defensive line between the frontline villages of Robotyne and Verbove.[2] Robotyne in particular was located less than 1.5 miles (2.4 km) from Russia's "main defensive line", and was described by officials and analysts at the time as "Ukraine's closest and most feasible path for breaking through the Russian line".[101] Ukrainian forces had broken through the first lines of defense, held by the 58th Combined Arms Army and GRU spetsnaz forces, causing Russian forces to fall back to a second line of defense. Russian forces later conducted a counterattack, recapturing the original line.[2] The ISW noted that the Russian Southern Military District, in charge of the defense of this line, acted with an "uncharacteristic degree of coherency" in their defensive operations. Russian sources offered various explanations for the success of the initial defense, such as effective mining, air superiority, and the use of electronic warfare (EW) systems.[2] U.S. officials and the Russian Ministry of Defence reported that the Ukrainian forces suffered "significant losses" during the attacks. At the time, U.S. officials said the losses were not expected to affect the counteroffensive as a whole.[79]

On 9 and 10 June, Ukrainian forces advanced in the area of Orikhiv with a mixture of Leopard tanks and Bradley Fighting Vehicles.[102][103] Also on 10 June, Ukrainian forces made further gains south and west of Lobkove.[103] On 11 June, the ISW reported that the 19th Motor Rifle Division of the 58th Combined Arms Army alongside the Tsar's Wolves militia, and the North Ossetian units "Storm Ossetia" and "Alania" were unable to hold onto Lobkove and withdrew, leaving the village in Ukrainian hands.[104]

On 18 June, a Russian-installed official, Vladimir Rogov, announced that the village of Piatykhatky in western Zaporizhzhia had been secured by Ukrainian forces,[105] which was confirmed with geolocated footage the following day.[106] Ukrainian gains in Robotyne, which had begun early in the month and continued throughout June,[107][108] culminated on 23 June, when Russian sources stated that Ukrainian forces broke through the Novodanylivka–Robotyne and Mala Tokmachka–Novofedorivka lines, and that Russian reserve forces had been mustered from the rear in an effort to stop these advances.[109] On 26 June, a spokesman for Ukraine's southern front forces, Valeriy Shershen, claimed that Russian forces had fired a "chemical aerosol munition with suffocating effect" on Ukrainian positions in western parts of the Zaporizhzhia region. Ukraine claimed that the wind had blown the "aerosol munition" back to Russian positions.[110]

On 27 July, there were widespread reports of Ukrainian troops breaching Russian defenses near Robotyne, and launching a "significant mechanized operation" to push toward the village.[111] The village would be the site of harsh urban combat starting from 11 August,[112][113][114] with fighting spilling over into neighboring Nesterianka and Kopani.[115]

On 17 August, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy made a frontline visit to the positions of 10th Operational Corps which included the Skala Battalion, the 46th Airmobile Brigade, the 116th Mechanized Brigade, the 117th Mechanized Brigade, and the 118th Mechanized Brigade.[116]

On 23 August, the 47th Mechanized Brigade hung the Ukrainian flag over the village's administrative building signalling that the urban center of the town was under Ukrainian control.[117][118][119] Full control over the village's southern outskirts would remain contested until around late August to early September when Russian troops reportedly withdrew.[120][121][122][123]

The importance of Robotyne, and why it was so heavily contested, was that it marked the southern edge of the dense Russian minefield along the front, which had effectively bogged down Ukrainian forces and prevented the efficient use of Ukrainian armor. With the recapture of Robotyne, Ukrainian troops were able to threaten the second line of Russian defenses.[124]

On 29 August, geolocated footage confirmed that Ukrainian forces advanced 5 km southeast of Robotyne and were de-mining the Robotyne area. Also on the 29th, Russian sources stated their situation in Verbove was "very dangerous".[125] On 30 August, Ukrainian troops entered the northwestern outskirts of Verbove.[126] On 23 September, Oleksandr Tarnavskyi announced that Ukrainian forces "have broken through in Verbove" and reiterated that the immediate goal for Ukrainian troops is the liberation of Tokmak, a major infrastructure hub for Russian forces.[127][128] On 24 September, bloggers affiliated with the VDV reported that Ukrainian forces had entered the urban portion of Verbove as well as overrunning a series of defensive networks north and west of the settlement, however, the ISW assessed they were likely exaggerating to make the Russian ministry of defense seem more incompetent so that Colonel General Mikhail Teplinsky, the commander of the VDV units around Verbove, could have greater independent command of the front-line.[129] On 25 September, geolocated footage confirmed that Ukrainian forces were present in urban Verbove.[130]

The importance of Verbove was that it is bordered on the north and the west by the second line of Russian defenses consisting of continuous prefabricated defensive structures, trenches, and ditches. The capture of Verbove meant that Ukraine had cut through this second line, also known as the Surovikin line.[131] Between Verbove and Tokmak is the third, and final, line of defense consisting of scattered defensive strong points and thin localized minefields.[132][133]

On 23 September, the ISW assessed that Ukrainian forces had cleared out all Russian troops between Robotyne and Novoprokopivka, a settlement directly south of Robotyne. The same day, Kyrylo Budanov reported in an interview that the Russian 2,500-strong 810th Guards Naval Infantry Brigade was "completely defeated, completely smashed", with the ISW assessing this as likely.[134][135]

On 19 October Ukrainian military observer Kostyantyn Mashovets claimed that Ukrainian forces advanced between 1.5 and 1.6 km into Russian defensive lines on the Robotyne direction.[136]

Berdiansk direction: Staromaiorske-Urozhaine

During 4 June, Ukraine made limited tactical gains in western Donetsk Oblast and eastern Zaporizhzhia Oblast, including northeast of Rivnopil.[137] The next day, Russian milbloggers reported accelerated Ukrainian offensive actions in eastern Ukraine, concentrated against the Novodonetske area, between Vuhledar and Velyka Novosilka in southern Donetsk Oblast.[138] Ukrainian forces made gains southwest of Velyka Novosilka and northwest of Storozheve.[139] Although Ukrainian officials remained largely silent on the matter, there was speculation that these offensive actions were the beginning of the long-awaited counteroffensive.[140] A Russian-appointed official in Zaporizhzhia Oblast said the Ukrainians aimed to break through Russian lines and reach the Sea of Azov.[87]

On the morning of 7 June, Ukrainian forces began storming Neskuchne.[141] Neskuchne had become an outpost of the Russian forces, with a complex geography: a hill on one side, and the Mokri Yaly river on the other. On a hill below the river there was a school in which a Russian fortified point was located. The village had been under Russian control for more than a year and there were several attempts to retake it which all ended in failure.[142] By 11 June, after four days of fighting the village had been recaptured by the 7th Battalion Arei of the Ukrainian Volunteer Army of and the 129th Territorial Defense Brigade of the Territorial Defense Forces.[141][143][144][145][146][147] Serhiy Zherbyl led Ukrainian forces in the battle.[142] Also on 11 June, Makarivka was retaken by Ukrainian forces.[148][149][150][104] As Russian forces withdrew from Makarivka, Major General Sergei Goryachev, chief of staff for the 35th Combined Arms Army, was killed in an "enemy missile attack", according to a Russian milblogger.[151] The Ukrainian military claimed Russian forces destroyed a dam on the Mokri Yaly river to slow down their advance.[152]

Also on 11 June, the 68th Jaeger Brigade, alongside several territorial defence battalions had recaptured the village of Blahodatne marking the third settlement to be retaken by Ukrainian forces during the counteroffensive.[153][154][155] The ISW assessed that on 10–11 June, Ukrainian forces had also recaptured Storozheve and Novodarivka in eastern Zaporizhzhia and western Donetsk but reiterated that claims of a Ukrainian "breakthrough" were premature.[104]

On 12 June, it was reported Ukrainians had also liberated Levadne, near to Novodarivka.[156]

In their 12 June report, the ISW assessed that fighting had shifted away from Orikhiv and reiterated claims of an advance along the Velyka Novosilka front. They also reported that Russian forces in the village of Rivnopil in southern parts of Donetsk Oblast are facing encirclement, but their exact situation is unclear.[157] On 24 June, Maliar reported that Ukrainian forces had liberated Rivnopil,[158] which was confirmed independently on the 26th.[159]

On 4 July, a Russian source claimed that Ukrainian forces reached the outskirts of Pryiutne, a village 15 kilometres southwest of Velyka Novosilka.[160] Pryiutne is a Russian logistical hub, being used to send supplies to all Russian forces on the Velyka Novosilka front. Should it fall, Russian forces would be forced to retreat to Staromlynivka and abandon several villages.[161] Russian sources claimed Ukrainian forces reached the outskirts of the settlement on 9 July and that there was heavy fighting in that direction.[162] On 14 July, Russian sources claimed that Ukrainian forces achieved a breakthrough towards Pryiutne, and also advanced 1.7 km towards Melitopol.[163] On 22 July, Russian state media claimed that Rostislav Zhuravlev, a war correspondent for RIA Novosti, was killed by a cluster munition strike against Russian forces in Pryiutne. Additionally, another RIA Novosti reporter was injured, alongside two Izvestia reporters, but none of their injuries were life-threatening.[164][165][166][167]

Starting on 16 July, there was heavy fighting in and around the village of Staromaiorske.[168][169] Ukrainian soldiers, speaking to Reuters, said their plans for the battle went awry, and they had faced a much tougher and bloodier battle than they had expected. One marine stated that the Russians "methodically destroyed the roads", and created "pits that prevented driving in and out of the village, even in dry weather. Even walking was quite hard. You can't use flashlights at night, but you still have to advance."[170] Despite these challenges, on 26 July, both Ukrainian and Russian sources confirmed that the village was recaptured by the Ukrainian armed forces.[171] It was considered to be a critical component of Ukraine's strategy in the South, and Zelenskyy himself had announced its liberation.[98] By the end of the fighting, the village was largely "ruined".[172]

Fighting continued south of Staromaiorske, towards the village of Urozhaine which was being defended by the Vostok Battalion, commanded by Alexander Khodakovsky.[173] The New York Times has called Urozhaine a "Russian stronghold", an important part of Russian defenses in the area.[172] Fighting for the village began on 6 August, when Khodakovsky claimed Ukrainian forces had "temporarily" crossed the stream separating Staromaiorske from Urozhaine.[173] The village would be the scene of heavy fighting as the Vostok Battalion was largely left to its own devices to defend the village.[174][175][176] On 15 August, Khodakovsky stated that Russian forces had lost the settlement and on 16 August, Ukraine announced that they had liberated the village with members and officers of the 35th Marine Brigade posing for pictures in front of the village's WWII memorial, which was heavily damaged in the fighting.[177][178][179] Russian forces retreating from the village took high casualties due to there only being one road out, the T0518, which Ukraine heavily shelled with both conventional and cluster munitions. Several Ukrainian drones captured footage of entire units being wiped out in artillery strikes along the road.[180]

Khodakovsky claimed that following the fall of Urozhaine, Ukrainian forces were attacking south-east, towards the village of Kermenchyk instead of south towards the village of Staromlynivka, which Reuters had described as a "stronghold."[178][113] On 30 August, Russian sources claimed Ukrainian forces had advanced towards Volodyne, 6 km southeast of Pryiutne and 7 km southwest from Urozhaine.[126]

On 6 September, both Russian and Ukrainian sources reported that Ukrainian forces had broken through the defensive lines of Novodonetske, 11 km east of Urozhaine, and that Russian forces had temporarily withdrawn from Novomaiorske, 6 km east of Novodonetske, following very heavy Ukrainian artillery bombardment with cluster munitions.[181] On 8 September, Russian sources claimed Ukrainian forces had entered the Northwestern outskirts of Novomaiorske.[182] Starting on 9 September, Ukrainian forces began a concerted effort to cross the Shaitanka river directly north of Novomaiorske and Novodonetske.[183]

On 14 September, Colonel Vasily Popov, commander of the 7th VDV Division's 247th Guards Air Assault Regiment, was killed in fighting in the Donetsk–Zaporizhia Oblast border area.[184][185][186] On 9 October, geolocated footage showed Ukrainian forces making gains towards Mykilske and Novofedorivka.[187] On 28 October, Ukrainian forces lost two more Leopard 2 tanks, with five total knocked out during a week of fighting in Zaporizhzhia Oblast, all by Russian FPV drone strikes.[188]

Eastern front

Oleksandr Syrskyi oversaw Ukrainian forces in the larger eastern campaign during the counteroffensive, especially in the Bakhmut direction.[99] During the first few months of the counteroffensive, Russian forces were in defensive positions along the vast majority of the frontline, with the Luhansk Oblast front being one of the few places where they were still on the offensive,[189][190] reportedly diverting Ukrainian forces from other fronts as of August 2023[update].[citation needed]

Donetsk Oblast

On 5 June, Ukrainian forces claimed to have advanced 200 to 1600 metres towards Orikhovo-Vasylivka and Paraskoviivka in the north, and 100 to 700 meters near Ivanivske and around Klischiivka. The ISW assessed that the Ukrainians advanced 300 meters to one kilometer in the direction of Zaliznianske and reiterated claims that portions or the whole of Berkhivka were recaptured.[86][191][88]

On 6 June, Ukrainian forces pushed Russian units past the eastern outskirts of Klishchiivka and there was ongoing fighting in Ozaryanivka, Ivanivske, Mayorsk, and Berkhivka.[192] By 7 June, Ukrainian forces had advanced between 200 and 1000 metres in the flanks of Bakhmut.[193]

On 8 and 9 June, Ukrainian forces advanced in the direction of Bakhmut, making gains of between 200 metres to 1.1 kilometres (0.68 mi).[194][107] On 8 June Ukrainian and Russian forces reported that Ukrainian forces advanced along the western bank of the Siverskyi Donets – Donbas Canal west of Andriivka, and forced the Russian 57th Motorized Infantry Brigade and a Storm-Z penal battalion to withdraw from their positions on the canal.[2] On 10 June, Russian milbloggers reported Ukrainian advances near Berkhivka and Yahidne, both near Bakhmut.[103]

By 14 June, Ukrainian forces were attacking the southwest, northwest and western axes of the city, as well as making continued gains in the city's flanks, especially along the Berkhivka Reservoir.[195] On 15 June, Hanna Maliar claimed Ukrainian advances near Bakhmut, but said that Russian forces were putting up "stiff" resistance.[196] Russian forces also conducted counterattacks in the vicinity of Bakhmut.[197] On 16 June, Colonel General Oleksandr Syrskyi described the fighting in Bakhmut, noting that Ukrainian forces attacked along multiple directions, with aims of taking "dominant heights and strips of forest" around the city to further the goal of "forcing the enemy gradually out of the outskirts of Bakhmut". He said that in response, Russia was sending its best divisions to Bakhmut, as well as artillery and aircraft.[198]

On 24 June, it was reported by a Ukrainian official that Ukrainian forces had liberated 0.51 square kilometres (130 acres) of territory near Krasnohorivka which had been occupied by Russia since 2014, in one of the first instances of such territory being recaptured by Ukraine during the war. The UK MoD assessed that it was "highly likely" the claim was true.[199][200][201] Hanna Maliar stated Ukrainian forces had made progress in "all directions".[202][203][204][205] The same day, the Wagner Group rebellion was underway, which was partially the result of internal Russian tensions during the battle of Bakhmut boiling over.

On 26 June, Syrskyi reported that Ukrainian forces had cleared a Russian bridgehead across the Siverskyi Donets – Donbas Canal which was being held by the Russian 57th Motor Rifle Brigade. Additionally, Russian sources claimed Russian forces performed an unsuccessful attack towards Ivanivske. The forces involved reportedly included BARS detachments, territorial troops, several Storm-Z units, and three PMCs: Patriot, Fakel, and Veterany.[159]

On 4 July, Ukrainian forces made significant advances towards Klishchiivka,[206] with Ukrainian advances threatening to cut off southern road access for supplies to Bakhmut, and had already begun moving artillery into the village to bombard Bakhmut from the south in support of other flanking maneuvers.[207][208] Ukrainian forces continued to make "tactically significant" advances in the area of Bakhmut through 7 July.[209] On 16 July, a Russian source claimed that Ukrainian forces had taken control of the village of Zaliznianske 13 kilometres (8.1 mi) north of Bakhmut.[168]

By 22 July, Ukrainian forces had dug in along their advances and Russian forces began counteroffensives to retake positions recaptured by Ukrainian forces; so far these counter-counterattacks have been unsuccessful.[210] On 23 July, Russian sources claimed that Ukrainian forces had entered the administrative limits of Khromove immediately west of Bakhmut and that there is heavy fighting in the settlement.[211] On 24 July, Deputy Defence Minister Hanna Maliar said that Ukrainian forces were advancing to the south of Bakhmut taking 4 square kilometres, but that to the north Russian forces were "clinging to every centimetre and meter".[212] On 25 July, Ukrainian forces have confirmed the use of US-supplied cluster munitions during combat in the Bakhmut sector.[213]

On 25 July, Ukrainian forces recaptured the tactically important heights overlooking Klishchiivka which allowed for uninterrupted artillery strikes into Bakhmut itself, as well as liberating the western half of the settlement. Ukrainian sources claimed this had effectively "trapped" Russian forces in the city, as any attempt to leave, or be reinforced, would be subjected to artillery strikes from Klishchiivka.[214][215][216]

On 5 August, deputy defense minister Hanna Maliar described the battle as "extremely fierce", with Ukrainian forces advancing slowly but confidently against the large number of Russian troops thrown at them.[217]

The Ukrainian 3rd Assault Brigade was tasked with the recapture of Klishchiivka, with their deputy commander, Maksym Zhorin, saying on 8 September that most of the village was under Ukrainian control.[218][219] On 9 September, the 3rd Assault Brigade also launched a concerted effort to recapture the neighboring village of Andriivka, located south of Klishchiivka.[183] Over the next days, the 3rd Brigade gradually advanced over booby trapped trench lines, charred forestry, and cratered open fields defended by Russian artillery, minefields, and grenades dropped by drones. The defenses made vehicle support sparse, and the Ukrainians were only able to evacuate injured comrades at night as the Russians hunted injured Ukrainian soldiers. The Ukrainians were reportedly spread across more than seven kilometers while advancing east of the Siverskyi Donets – Donbas Canal —a canal located south of the Siversky Donets river itself and south of Bakhmut. Ukrainian assault teams waged daily small assaults until they reached the outskirts of Andriivka.[220][221]

Meanwhile, on 10 September, Avdiivka City Military Administration Head Vitaliy Barabash reported that Ukrainian forces had gained a foothold in the urban portion of the village of Opytne 3 km southwest of Avdiivka and 2 km north of the Donetsk International Airport.[222][223] Maliar reiterated on 11 September that portions of Opytne were liberated, and that Ukrainian forces were still making progress in the village.[224][225] On 13 September, there were reports of fighting to the south west of Opytne, although there has yet to be an official statement of the village's recapture from the Ukrainian ministry of defense.[226] On 14 September, Russian milbloggers circulated a video of a retreating Russian column about 200 strong leaving Opytne for "more favorable positions" being struck by Russian artillery. Yuriy Mysiagin, a member of the Verkhovna Rada, reported that the friendly fire incident killed 27 Russians and injured 34 more.[227]

The 3rd Brigade broke into Andriivka on 14 September from the south, deploying smoke screens and capturing some Russian troops while clearing houses. Even after the Russians retreated, the village remained under artillery shelling and drone warfare. All that remained of Andriivka was piles of bricks, ruined houses, and scorched forestry.[220] Hanna Maliar preemptively announced the liberation of Andriivka on 14 September, which was rebuffed by the 3rd Brigade which announced that the village was actually liberated on 15 September, with troops hoisting a flag there on 16 September.[220][228][229][230] Later in the day, the Kastuś Kalinoŭski Regiment and Chechen volunteers in Klishchiivka reported that all Russian units had been expelled from Klishchiivka as well, publishing a video showing members of the unit walking the length of the village freely and unopposed. Elements of the 3rd Assault Brigade claimed to have killed four senior officers of the Russian 72nd Separate Motor Rifle Brigade, which had been tasked with the defense of both Klishchiivka and Andriivka since the start of the renewed fighting, and claimed to have encircled and destroyed most of the unit.[231]

On 17 September, Ukraine's interior minister Ihor Klymenko and general Oleksandr Syrskyi announced that Klishchiivka was fully cleared of Russian forces, with President Zelenskiy congratulating the 80th Air Assault Brigade, 5th Assault Brigade, 95th Air Assault Brigade, and the Liut Brigade of the Offensive Guard for their role in the village's liberation on the morning of 18 September.[232][233][234] Also on 18 September, Aleksandr Khodakovsky reported that Colonel Andrey Kondrashkin, commander of the 31st Guards Air Assault Brigade, which had been in charge of the overall defense of Andriivka and Klishchiivka, was killed in battle.[235]

In total, three Russian brigades were tasked with the defense of Andriivka and Klishchiivka, the 72nd Separate Motor Rifle Brigade, the 31st Guards Air Assault Brigade, and the 83rd Guards Air Assault Brigade, which the 3rd Assault Brigade claims were all no longer capable of combat.[236] To contain the Ukrainian advance, Russian troops had reportedly dug small trenches and deployed anti-tank hedgehogs along the railway line along Klischiivka and Andriivka's respective outskirts, which guarded the T0513 Bakhmut-Horlivka highway. On Bakhmut's northern flanks, the Ukrainians did not launch major ground assaults as the Russians held the high ground despite daily sniper and artillery exchanges.[221] On 23 September, HUR head Kyrylo Budanov reported that although the gains in the Bakhmut direction were welcome, the overall goal of Ukrainian forces in the region were to pin Russian forces in a defense effort that would otherwise be used to reinforce the front in Southern Ukraine.[134]

By 1 October, the Ukrainians had advanced east, north, and south of Klishchiivka and Andriivka in attempts to recapture the railway. The Ukrainian military said the Russians had concentrated 10,000 personnel in Bakhmut itself, meanwhile Russian sources claimed Russian forces were preventing Ukrainian troops from advancing past the railway line amid continuous local assaults.[237] By 12 October, the Ukrainians continued to report unspecified gains of "hundreds of meters" in south Bakhmut while repelling all Russian counterattacks, while Russian forces claimed to have repelled Ukrainian advances along the Klishchiivka-Andriivka-Kurdiumivka line.[238] However Ukrainian troops had reportedly crossed the railway north of Klishchiivka by 24 October amid ongoing clashes, with Captain Ilya Yevlash stating on 18 October that Ukrainian forces had crossed the railway line south of Bakhmut, presumably east of Klishchiivka.[136] The Ukrainians also claimed successful counterattacks near Khromove and Bohdanivka, along Bakhmut's western environs.[239]

By late October, Ukrainian troops reported having logistical issues on the Bakhmut front, with multiple artillery units preserving shells due to a severe lack of ammunition, particularly mortar rounds, with the Zaporizhzhia front taking priority in artillery supplies.[221]

Starting on 10 October, three motorized rifle brigades of the Russian 8th Combined Arms Army began a concerted offensive action towards Avdiivka, seeking to encircle the city.[187] Geolocated footage showed that the main efforts of the Russian offensive was the southwest near Sieverne and northwest near Stepove and Krasnohorivka.[240]

Dnieper front

On 6 June, the Kakhovka Dam on the Dnieper was destroyed, flooding vast areas downstream and reducing water supplies to Crimea.[241][242] Many experts have concluded that Russian forces likely blew up a segment of the dam to hinder the planned Ukrainian counteroffensive.[243][244] The Ukrainian army had begun making plans to retake the Dnieper delta islands, as they had provided a good location to observe Russian military activities, and began staking out the location ahead of the counteroffensive. Tactical units had previously conducted reconnaissance and targeting operations against the Russian defensive lines. However, the destruction had significantly disrupted these plans, which impacted the overall counteroffensive.[245]

On 26 June, pro-Russian Telegram channels claimed that Ukrainian forces crossed the Dnieper and captured the district of Dachi in an attempt to establish a bridgehead.[246] On 29 June, Vladimir Saldo, the Russian-installed Governor of occupied Kherson Oblast, stated that the Kherson volunteer militia "Vasily Margelov" had been sent to the Antonivsky Bridge and was conducting combat operations alongside BARS detachments.[68] Fighting for Dachi and the island it is on, Antonivsky Island, would continue until 11 July, when Russian forces abandoned their positions claiming it to be a "justified and measured" action, citing the swampy and difficult to attack terrain and heavy Ukrainian artillery bombardments.[247]

On 8 August, there were widespread claims from Russian milbloggers that Ukrainian military boats had crossed the Dnieper River elsewhere, landing near the village of Kozachi Laheri. The Institute for the Study of War reported that satellite footage suggested there had indeed been major fighting in the area.[248] On 9 August, Russian major Yuri Tomov surrendered his battalion sized unit which was in charge of the defense of the western outskirts of Kozachi Laheri to Ukrainian forces.[249] On 11 August Russian sources claimed that Ukrainian forces controlled half of Kozachi Laheri and had performed a raid against a convoy along the E58 highway.[112] Since their initial landing, Ukrainian Special Forces have performed a series of raids to the west of the settlement, maintaining landing sites and a series of observation posts, securing control over a region 800 meters deep into the eastern bank of the river.[250][251] Tanks were successfully forded across the river to reinforce these positions on 14 August.[252] Operations have also been supported by artillery batteries on the west bank of the river.[253] Ukrainian forces have been sending captured intelligence and Russian soldiers across the river for processing.[254][255] At some point early in the landings, Ukrainian forces captured the western outskirts of Kozachi Laheri, but retreated by 18 August.[256]

On 19 August, the Ukrainian armed forces commented on the operations in the Kherson Oblast for the first time, with spokeswoman Humeniuk announcing that operations up to this point were to set conditions for the security of future operations and maneuvers on the left bank of the Dnieper, namely, clearing Russian artillery batteries that would prevent a full scale river crossing.[257]

Russian sources claimed that on the night of 17–18 October Ukrainian forces crossed the Dnipro and temporarily controlled and partially control the villages of Poima and Pishchanivka, respectively.[258] Additionally, Russian sources reported raids against Russian positions in the village of Krynky and on Kazatsky Island. The Russian sources stated that the attacks were perpetuated by the 35th and 36th Marine Brigades and that besides artillery bombardments, that no Russian force were sent to stem the bridgehead.[259] On 19 October, Vladimir Saldo disputed earlier claims that no Russian forces were sent to clear out the Ukrainian bridgehead, reporting that the Poyma-Pishchanivka-Pidstepne area had been cleared of Ukrainian personnel. Other Russian sources reported that Ukrainian marines entered the village of Krynky and the Ukrainian general staff reported a Russian air strike on Pishchanivka, a report usually reserved for strikes on Ukrainian held positions.[136]

On 19 November, the Ukrainian army vaguely claimed that it had advanced between "3–8 kilometers" along the occupied bank of the Dnieper.[260][261]

Behind front lines

Crimea and the Black Sea

On 30 July, the Chonhar railway bridge, the major rail connection from Crimea to the rest of Russian-controlled southern Ukraine, was confirmed to have been severely damaged to the point of being nonoperational by a strike from the Ukrainian Armed Force.[262] On 6 August, another bridge, this one being a road bridge spanning the Henichesk Strait, connecting Henichesk Raion in Kherson to the Arabat Spit, was struck by several Ukrainian missiles, according to Vladimir Saldo, the Russian installed governor of occupied Kherson Oblast. The bridge had replaced the Chonhar bridge as the major route for Russian supplies into Kherson, and the strikes have left it partially collapsed and inoperable.[173] Saldo announced that the bridge was once again operational and traffic had resumed on 17 August.[263]

On 23 August, GRU released a video of a Russian S-400 missile system in Olenivka, Crimea, 120 km south of Kherson, being struck by Ukrainian missiles resulting in its total destruction and the death of several Russian military personnel in the vicinity.[124] On 24 August, HUR announced that Air Force and Navy intelligence was involved in a special operation near the towns of Mayak and Olenivka on the Tarkhankut Peninsula which saw an amphibious landing and airborne deployment of Ukrainian personnel on Crimea. HUR announced that all objectives of the operation were completed, Russian forces suffered casualties, and that the Ukrainian state flag once again flew over the Crimean peninsula.[264][265][266]

On 27 August, the UK's Ministry of Defense reported that there were a series of skirmishes between Ukrainian naval personnel and Russian air force elements on and around oil platforms in the Black Sea. Previously, both Russian and Ukrainian personnel have been stationed on the platforms, and a series of Russian controlled platforms were struck by Ukrainian missiles.[267] On 11 September, HUR reported that it had recaptured two of the offshore "Boyko Rigs"; Petro Hodovalets and Ukraina (renamed Tavrida during Russian seizure in 2014). The drilling platforms had been occupied by the Russian military since 2015. During the operation the rig's Neva radar stations and several Russian personnel were captured and a SU-30 that was sent to dislodge the Ukrainian personal was damaged.[268]

On 13 September Ukraine launched a salvo of cruise missiles at the Sevmorzavod dry dock in Sevastopol. Footage confirmed that the strikes heavily damaged one Kilo class submarine, the Rostov-on-Don, to the point of being inoperable and no longer seaworthy. The Russian navy has vowed to repair the submarine, despite the only sufficient repair yards for a Kilo class submarine being at the Leningrad Naval Base and there being no way to feasibly float the hulk due to the shutting of the Bosporus to military craft in accordance to the Montreux Convention since the start of the invasion.[269] Besides the two gaping holes below the water line, the Storm-Shadow missiles used in the strike utilized a tandem-charge with the primary charge punching a relatively small hole for the second, much larger warhead, to detonate in the interior of the submarine meaning the damage to the inside of the submarine is worse than the damage to the outside. As such, Forbes military correspondent David Axe called Russia's claims they will repair the submarine "laughable."[270] Additionally, the strike destroyed a Ropucha-class landing ship, the Minsk, and left the dry docks and repair facilities inoperable indefinitely.[271]

On 14 September, the Department of Strategic Communications of the Ukrainian Armed Forces announced that a Russian S-400 Triumf surface-to-air missile battery was destroyed near Yevpatoria in Crimea after being hit by two Neptune cruise missiles.[184]

On 15 September two Project 22160 patrol ships were struck by Ukrainian naval drones, resulting in significant damage and forcing both ships to return to port.[272][273][274]

On 22 September, Ukraine struck the headquarters of the Russian Black Sea Fleet.[275] HUR reported that the operation effectively decapitated Russian command, leaving dozens of high-ranking officers dead "including the senior leadership of the fleet."[276][277][278]

On 4 October, HUR reported that they had performed a raid in Crimea, publishing a video of operatives firing at Russian positions. The Russian defence ministry said that a Ukrainian raid on Cape Tarkhankut, which had included jet-skis and speedboats, had been repelled by the Russian air force; Russian milbloggers claimed that Ukraine had suffered casualties while no Russians had died.[279]

Crimea, and southern Russia and occupied Ukraine, was hit by Storm Bettina, leaving at least four dead and a dozen wounded, as well as over 500,000 without power.[280][281] Additionally, the storm washed away most Russian coastal defense positions, leaving the peninsula vulnerable to increased Ukrainian raids.[282][283]

Other areas

On 30 June, the Ukrainian military claimed to have struck a Russian headquarters and a fuel and lubricant warehouse in Berdiansk Airport with 10 Storm Shadow missiles. The airport has been used by Russian helicopters defending against the 2023 Ukrainian counteroffensive, with satellite imagery showing 29 helicopters based there a fortnight ago. Russian forces claim to have shot down at least one missile.[284][285]

On 11 July, Lieutenant-General Oleg Tsokov was killed in a Storm Shadow missile attack in the Zaporizhzhia region. He was the deputy commander for the Russian Southern Military District, making him the highest ranked Russian officer killed during the war.[286][287]

On 19 August, Ivan Fedorov and GRU reported an explosion in the headquarters of the Russian installed Enerhodar occupation police chief, Colonel Pavel Chesanov, which required Chesanov, and several other high-ranking officers, needing to be medically evacuated to Russia via helicopter.[257]

On 4 October, the Ukrainian General Staff reported to have repelled an effort by the Russian army to cross the border from the Belgorod Oblast into the Kharkiv Oblast near the village of Zybyne.[279]

On 17 October, HUR reported that its Operation Dragonfly destroyed nine parked helicopters, anti-air defenses, fuel depots and ammunition dumps as well as leaving "dozens" of Russian personal dead or wounded in a series of strikes with ATACMS missiles on the Berdiansk and Luhansk airports.[288][289][290]

On November 27, Oleksiy Danilov, National Security and Defense Council Secretary, stated that in the past few months Russian intelligence activated a series of Russian sleeper agents to destabilize Ukraine and fragment the civilian population's opinion on the war, namely by targeting the Ukrainian female population and relatives of active soldiers. Danilov also stated that these agents have been present in Ukraine since the collapse of the Soviet Union, as many Soviet intelligence assets with loyalties to Moscow were never followed up on by Ukrainian intelligence.[280][291][292]

Result

Around five months after the counteroffensive began, Ukrainian forces captured 370 km2 of territory, less than half of the amount Russia captured earlier in the year.[52] They also conducted a number of successful attacks on the Russian-occupied Crimean Peninsula and against the Russian Black Sea fleet. The offensive reached culmination as Ukraine had no more assault-capable infantry and artillery shells supplied from the West.[293] Ukraine did not reach the city of Tokmak, described as a "minimum goal" by Ukrainian general Oleksandr Tarnavskyi,[56] and the probable initial objective of reaching the Sea of Azov to split the Russian forces in southern Ukraine remained unfulfilled.[57][58][6] Ukrainian commander-in-chef Valerii Zaluzhnyi stated in early November 2023 that the war had arrived at a "stalemate".[53][54]

In an interview on 30 November, president Zelenskyy said the war was entering a new phase and he gave a mixed answer regarding the results of the offensive.[55] As of early December 2023, multiple international media outlets described the Ukrainian counteroffensive as having failed to regain any significant amount of territory or meet significant strategic objectives.[59][60][61][62][63][5] Among the causes for the failure researchers mention Ukraine's lack of advantage in firepower, not having necessary minefields breachers to overcome excessive Russia-prepared minefields, and inability to scale up force employment to exploit breaches in the Russian lines. Ukraine's effort was split in three axes, and this strategy was not adjusted after the initial breaching effort failed.[293]

As of December 2024, Russia recaptured eight out of the 14 villages captured by Ukraine in the 2023 counteroffensive: Andriivka, Blahodatne, Klishchiivka, Levadne, Rivnopil, Robotyne, Staromaiorske and Urozhaine.[294]

Strengths

Personnel

Philippe Gros, a researcher for the French think tank Foundation for Strategic Research, said on 13 June 2023 that there was "more or less parity" in the total strength of the opposing forces. He said that the number of Russian troops was between 350,000 and 400,000, and "the Ukrainians probably have a little more".[295] From the Ukrainian total, twelve brigades, amounting to about 35,000 troops, were created specifically for this offensive and were equipped with modern Western armor.[6] American Department of Defense officials said on 1 August that Ukraine had committed 150,000 soldiers to the offensive so far.[296]

On 10 September, GRU spokesman Major General Vadym Skibitskyi reported that there were 420,000 Russian military personnel in occupied Ukraine, not including Rosgvardia and other irregulars. That same day Ukrainian Defense Minister Rustem Umerov stated that there are currently one million active Ukrainian Defense Forces personnel, with 800,000 serving in the ranks of the Armed Forces, although, not all of these are taking part in the counteroffensive.[222]

Equipment

On 1 September 2023, Estonian Colonel Margo Grosberg, commander of the Estonian Defence Forces' intelligence section, said in an interview that Ukraine's artillery was equal to or even better than Russia's.[297] Brigadier General Serhii Baranov also said in an interview that Ukrainian artillery had "now achieved parity in their counterbattery capabilities" against Russian systems, due in part to the longer ranges of Western supplied systems.[298]

Casualties and losses

In mid-June, the British Ministry of Defense wrote that both Russian and Ukrainian forces are suffering "high casualties" in the south area of fighting, further stating that Russian casualties were the highest since the peak of the worst fighting in Bakhmut in March 2023.[299]

Ukraine

Ukraine suffered heavy casualties during the counteroffensive.[300] Western officials have said that such losses were not unexpected for attacking forces.[301] The New York Times reported that Ukraine's equipment losses were as high as 20% of the weaponry sent to the battlefield during the beginning of the offensive. This forced Ukraine to change tactics to focus more on attrition-based artillery and missile strikes against Russian positions, reducing the rate of loss to an estimated 10%.[clarification needed][51]

On 17 August, ABC News interviewed a wounded American volunteer, who said that his unit had taken "85% casualties". Another American volunteer from Alaska said it was immediately apparent that they were up against "very organized resistance" from Russian troops.[300]

According to Western military analyst Donald Hill, Russian production of drones and other weapons has taken a serious toll on the attacking Ukrainians, with some brigades involved in the offensives losing over 50% of their vehicles damaged or destroyed.[302] According to a report by Forbes on 9 October, Ukraine's success in just advancing to within artillery range of Tokmak cost them hundreds of vehicles and would "potentially" cost thousands of lives[vague].[303]

According to Western analysts, the Ukrainians had lost 518 vehicles in Zaporizhzhia as of 10 November visually confirmed, compared to 600 Russian losses.[304] In a later report by Forbes, the Ukrainians were said to have suffered "roughly" the same losses as the Russians during the counteroffensive, in both troops and vehicles.[305]

According to claims by the Russian MoD, the Ukrainians had lost over 90,000 wounded and killed personnel, almost 600 tanks and around 1,900 armored vehicles during the counteroffensive, although the ISW considered these to be "implausible".[306]

Russia

Ukrainian Brigadier General Oleksandr Tarnavskyi wrote on Telegram in mid-June that Russia's "losses in killed and wounded amounted to more than four companies."[198]

According to claims made by the ZSU, Russian forces had suffered 15,000 casualties per month during the counteroffensive, with perhaps 25,000 lost during August 2023 alone. The four BARS regiments operating near the Robotyne area, each one with an established strength of 1,000 men, have been reduced to a total strength of just 300 men each. This is equivalent to just two companies, or to a "weak" battalion.[307]

During the Ukrainian counteroffensive south of Bakhmut, the Russian 72nd Separate Motor Rifle Brigade had reportedly suffered over 4,000 casualties over a few months. During the recapture of Andriivka in mid-September, the Ukrainian 3rd Assault Brigade encircled and claimed to largely destroy the brigade. According to a report by Forbes, "in two days of hard fighting, the 3rd Assault Brigade claimed it killed the chief of intelligence of the 72nd MRB [Motor Rifle Brigade], many of the Russian brigade's officers 'and almost all the infantry.'" Russian casualties – dead, wounded and captured – were reported to possibly number a thousand or more, with dozens of POWs taken.[308][302]

On 14 June, Vladimir Putin said Russia had lost 54 tanks, comparing the number to Ukraine's allegedly greater number of losses.[309]

By 10 November, BBC News Russian confirmed by name a minimum of 3,755 Russian soldiers who died during the counteroffensive.[310]

Analysis

Timeframe and progression

Western officials spoke in June 2023 about the expected high difficulty and length of the counteroffensive for Ukraine.[301][311] For example, anonymous Western officials speaking to The Guardian noted the possibility of "grinding costly warfare likely for many months to come" due to Ukraine fighting against Russian preparations.[301] Two Western officials and a senior US military official told CNN that Russian forces appeared to be more "competent" than Western assessments had expected.[312] The same month, US Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Mark Milley warned that they expect the fight to be long and come "at a high cost."[311] Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy said by 21 June that the counteroffensive was progressing "slower than desired" while also affirming that Ukraine will "advance on the battlefield the way we deem best" and would not agree to a frozen conflict.[313]

On 3 July, Dutch Admiral Rob Bauer, Chair of the NATO Military Committee, described the counteroffensive as "difficult" and compared it to the fighting in the Normandy campaign: "We saw in Normandy in the Second World War that it took seven, eight, nine weeks for the allies to actually break through the defensive lines of the Germans. And so, it is not a surprise that it is not going fast." Bauer expressed his view that Ukraine should not be forced to move at a faster pace, saying current operations are "commendable".[314] Mykhailo Podolyak, Advisor to the Office of the President of Ukraine, used a similar description on 15 June, announcing that the counteroffensive had not yet begun, and that all fighting up until that time had been preliminary probing actions.[96] Addressing criticism of the perceived slow speed of the counteroffensive, Peter Dickinson of the Atlantic Council considered its pacing to be deliberate and compared it to a marathon meant to exhaust Russia rather than a blitzkrieg, with the 2022 Kherson counteroffensive potentially serving as a precedent.[315] Oleksii Reznikov, Ukraine's Minister of Defense, also rejected comparisons of the counteroffensive to a blitzkrieg and stated that operations hitherto were "some kind of preparatory operation". Additionally, Ukraine also selectively puts soldiers in battles in order to save their lives, while Reznikov described the Russian approach as using their troops as "meat grinder".[316] Zelenskyy also reiterated similar sentiments; he stated that the counteroffensive's pacing had slowed in order to save people's lives, and that he had prioritized saving lives over progressing quickly.[317] Konrad Muzyka, a Poland-based military analyst, said that as of 15 June, only 3 of the 12 Ukrainian brigades prepared for the counteroffensive had been seen in combat in the southeast.[318]

By July, US officials had assessed Ukraine had begun intensifying their counteroffensive by deploying more troops into battlefields, including Western-trained troops held in reserve since the beginning of the counteroffensive, noting a flare-up of artillery battles along the Zaphorizhzhia frontlines. Vladimir Rogov, a Russian-installed official in the Zaphorizhzhia region, stated Ukrainian troops managed to breach frontlines after conducting several wave attacks along with reinforcements from over 100 tanks.[319] On August, the Institute for the Study of War published a rebuttal to negative forecasts of the counteroffensive. They stated that even if Ukrainian forces fell a few miles behind Melitopol, this would allow Ukraine to target Russian "road and rail" ground lines of communication.[320] Later analysis showed that in August, the least territory changed hands of any month since the invasion started.[52]

In September, White House National Security Council spokesman John Kirby stated the US noted progress by Ukraine in the Zaporizhzhia area, particularly in progression against the second line of Russian defenses. Ukrainian Deputy Defence Minister Hanna Maliar later confirmed that in "certain areas", Ukrainian forces had breached the first line of defenses in the Zaporizhzhia region.[321] US General Mark Milley estimated by September 10 that Ukraine had approximately 30–45 days left to continue its counteroffensive until colder conditions and autumn rains would undermine Ukrainian mobility, particularly for military vehicles.[322] The next month, Ukraine's Main Intelligence Directorate chief, Kyrylo Budanov, said that Ukraine had fallen "out of schedule" in its counteroffensive, as opposed to having fallen "behind", refraining from further elaboration.[57]

In the following months, various Western analysts and militaries began assessing that Ukrainian forces made limited progress and that their advances had stalled. Notably, on October 19, researcher Jack Watling, at the British think tank Royal United Services Institute (RUSI), concluded that "Ukraine retains certain options to make the Russian system uncomfortable, but it is very unlikely that there will be a breakthrough (...) this year".[6] That November, Ukrainian general Valerii Zaluzhnyi conceded the war had stagnated, describing it as a WW1-style stalemate and felt a breakthrough would not occur unless a "massive technological leap" occurred. He felt the counteroffensive undermined Western hopes to show Russian President Vladimir Putin that the war was "unwinnable", and that inflicting heavy casualties would not be enough. He lamented that his troops, including "newly formed and inexperienced brigades" in the south, got stuck in minefields and that Western-supplied equipment got "pummeled by Russian artillery and drones". According to him, NATO calculations during the planning period estimated Ukraine would be able to advance 30 km a day. Furthermore, he compared Russia's recent offensive in Avdiivka and the issues they faced to the Ukrainian offensive, noting the "same picture unfolds when Ukrainian troops try to advance".[323]

Significance and goals

The Ukrainian counteroffensive initially drew comparisons to D-Day, with the operation seen as a pivotal moment in the war that would influence the outcome.[324][325] Analysts regarded successes as unequivocally demonstrating that Western military aid to Ukraine was justified and that a comprehensive Ukrainian victory was possible, which would encourage further aid. However, opinions on what would constitute a success varied among Western leaders. Ultimately, American and European officials allowed Zelenskyy to determine what he viewed as a "success." Two essential components of success would include the Ukrainian army retaking Russian-occupied territories and/or undermining the Russian military.[326] Depending on the specific goals of the offensive, victory could weaken Russia's strategic position in the war while also ensuring that Ukraine receives long-term security guarantees from the West.[327] Zelenskyy had also desired to show results to Western allies prior to the 2023 Vilnius summit.[317]

Analysts have seen breaking the Russian land bridge to Crimea in the Zaporizhzhia region as a central goal of Ukraine's counterattack.[42] A major Ukrainian breakthrough in the region could "severely" threaten the viability of the land bridge, serving as the main supply route for Russian military strongholds in Crimea.[328] Alternatively, recapturing the Zaphorizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant would be seen as a symbolic victory while also re-providing Ukraine with critical infrastructure assets.[326] According to the UK MoD, Russian forces had been reinforcing Crimea: "This includes an extensive zone of defences of 9 km in length, 3.5 km north of the town Armyansk, on the narrow bridge of land connecting Crimea to the Kherson region."[329]

In a speech to parliament, UK Defence Secretary Ben Wallace said that Ukraine in its summer campaign had captured "300 square kilometers" of territory, which he said was more than Russia achieved in its winter offensive.[330][331] On 4 July, the ISW noted that despite the overall goal of the counteroffensive being to recapture Russian-occupied Ukraine, the immediate goal of Ukrainian forces is "creating an asymmetrical attrition gradient that conserves Ukrainian manpower at the cost of a slower rate of territorial gains, while gradually wearing down Russian manpower and equipment", focusing their efforts and ammunition on "destroying Russian manpower, equipment, fuel depots, artillery, and air defenses." ISW also compared the offensive to the earlier Kharkiv counteroffensive and the Russian winter offensive, and assessed that the 2023 counteroffensive was most similar to the Kherson counteroffensive, with small but consistent gains and an overall goal of whittling down Russian forces.[160]

On 10 July, ISW noted that Ukrainian forces recaptured approximately 253 square kilometers of territory. Meanwhile, Russian forces have captured a total of 392 square kilometers in the entire theater since 1 January.[332] On 5 July, Admiral Sir Tony Radakin, UK Chief of the Defence Staff, told parliament that Ukraine's aim was to "starve, stretch and strike" Russian defensive lines. He also acknowledged that Russian minefields were "stronger than expected".[333] The New York Times reported that during 2023 up to September 25, Ukraine gained 143 square miles (370 km2) while Russia gained 331 square miles (860 km2) of territory, a net gain of 188 square miles (490 km2) by Russia, from analysing Institute for the Study of War and American Enterprise Institute Critical Threats Project data. The changes were assessed to be not significant but a prolonged stalemate.[52]

Concerns

As part of the 2022–2023 Pentagon document leaks, secret February 2023 documents had indicated that the US was worried about the success of the counteroffensive, predicting it would only result in "modest territorial gains" while also citing issues in the Ukrainian military, including troops, ammunition, and equipment.[334] CNBC opined that the beginning of the counteroffensive was deemed as "underwhelming" by some, but noted that Ukrainian actions up until 15 June had been probing attacks, and not the main phase of the counteroffensive; military operations were performed to assess Russian defenses, as they had been preparing for the counteroffensive months prior, identify the weakest points, and secure adequate bridgeheads for the main Ukrainian force.[335] Similarly, on 9 June, the ISW assessed that Ukraine had not committed its full reserves and western equipment to the counteroffensive as of 9 June, and that material losses sustained up to that point would not necessarily impact the course of the counteroffensive.[107]

Austrian historian and military analyst Markus Reisner deemed the first phase of the counteroffensive to be a failure as Ukraine had tried to emulate tactics of the US military by advancing in huge numbers. However, he also noted that Ukraine had changed its tactics by slowing down its pacing and instead attacking in slower groups, which he felt was a better tactic for success.[336] On 12 October, the analyst concluded that the counteroffensive had "failed, especially from an operational perspective", citing Ukrainian General Kyrylo Budanov who recently said that its goals had not been achieved. He also highlighted growing disillusionment in Ukraine and concerns of a possible decrease in flow of military aid from the US given increasing domestic pressure and the 2023 Israel–Hamas war.[54]

In an interview on November 1, Ukrainian general Valerii Zaluzhnyi showed concern that the deliveries of F-16s planned for 2024 would be "less useful" because Russia already had the time to improve its air defenses, most notably its S-400 missile system. He claimed that Western allies were overly cautious in sending their latest technologies and that weapon deliveries were ultimately being held back in an attempt to sustain Ukraine in the war, but not let it possibly win. He also made the assessment that without a major technological breakthrough in sight, Russia would have the advantage in a near stalemate/long war by having much greater human and natural resources. In the meantime, the Ukrainian state could be worn down, he suggested.[323] In 2024 assessment, war studies researchers agree with Zaluzhniy on late weapons delivery consequences, saying "Ukraine requested these weapons systems ahead of the operation, and if it had received them in sufficient quantity, the counteroffensive might have been successful. But without them, it was doomed. The United States and other partners initially withheld these arms out of fear of escalation, and by the time they greenlighted shipments, it was too little too late to make a difference in the summer campaign." While weapons deliveries were on hold, Russia prepared fortifications, mobilized and trained its manpower, and increased the military industry production.[337]

Tactics and equipment

Russian minefields and fortifications

The Ukrainian counteroffensive faced a dense net of Russian fortifications, minefields, and anti-tank ditches.[338] Ukrainian officials have acknowledged that the offensive has been slowed by Russian minefields.[339] There are other reports of Ukrainian units using remote controlled vehicles such as the BMP-1 on minefields that was stopped by anti-tank ditches. Ukrainian forces had an insufficient amount of breaching equipment; Oryx reported that Ukraine has less than 30 minefield breaching vehicles when they would require double that to operate under fire. Other equipment supplied was suitable for humanitarian but not military mine clearance. Mine plows, which would allow Western supplied tanks to advance through a minefield whilst under fire, had been supplied by the West but in insufficient numbers. Also, in an interview with a Ukrainian Leopard tank crew, the latter explained that during training in Germany, instructors had drawn minefields that were "100 by 200 meters in size" but that the crew had to face Russian minefields that were measured in "hectares".[340][341] Retired Major General Mick Ryan told Reuters that the Russian minefields were similar to the Iraqi minefields during the 1991 Gulf War at 2-5 kilometres deep, numbering in the tens of thousands of mines, while Russian minefields in the south, might approach "hundreds of thousands at a minimum" according to Ryan.[342]

On 13 August, Ukrainian Defence Minister Oleksii Reznikov claimed that Ukraine was the most "heavily mined country in the world", with soldiers encountering up to five mines per square metre in some parts of the front and shortages in equipment and personnel trained as sappers to remove the mines. Those existing trained personnel and equipment have sustained heavy casualties. He said: "Russian minefields are a serious obstacle for our troops, but not insurmountable. We have skilled sappers and modern equipment, but they are extremely insufficient for the front that stretches hundreds of kilometres in the east and south of Ukraine."[343]

Along the Melitopol axis, Ukrainian officials have stated that maneuver warfare is impossible due to the density of the Russian minefields, and the sandy complexion of the soil. As such, Ukrainian generals have had to revert to strategies that haven't been used in any modern war since World War 2. Namely, they have been utilizing "sneak and peak" tactics, where small infiltration groups perform stealthy reconnaissance to clear a path through minefields, then with the support of artillery and air support, the small infantry teams can attempt an assault on the settlement in either an attempt to capture it, or cause the Russian unit defending it attrition. The small size of these raid teams, and the length of the operations they perform, has been attributed as contributing to the slow pace of the counteroffensive along the axis.[344]

In late July, General Oleksandr Tarnavskyi said that the number of minefields mean that the advance must be undertaken by soldiers and not armoured units. A repair workshop had a dozen vehicles that needed repair, mostly M2 Bradleys. The BBC reported that Mastiff armoured vehicles, supplied by Britain, had also been damaged and destroyed. The 47th Mechanized Brigade, fighting in southern Ukraine, has had to turn to its older Soviet-era equipment such as the T-64 tank. These tanks are fitted with rollers to try and detonate landmines. However Russian mines are being stacked on top of each other. One T-64 commander said that a roller was destroyed after one explosion when typically it could withstand four explosions. Russian forces have started to leave trenches abandoned but filled with remote controlled mines. Once Ukrainian forces entered the trench there is an immediate explosion.[345]

Artillery and aerial warfare

Ukrainian forces were also hampered by the lack of substantial air support along the frontline, due to the Russian air defenses forcing Ukrainian aircraft to fly low and to launch rockets from afar.[338] The forces that Ukraine were relying on for the counteroffensive were well trained but not combat experienced.[346] In one of its daily updates, UK MoD intelligence noted an increase of sorties by Russian aviation since the counteroffensive began. Given the lack of air defence Ukraine's allies have had to increase the amount of aid for air defence systems. The Joint Expeditionary Force has promised Ukraine $166.2 million in air defence weapons both for civilian and "front-line" use.[347]

The Ukrainian counteroffensive lacks short range, or SHORAD, air protection for its forces, making its armour vulnerable to attack helicopters, drones equipped with improvised explosive devices or loitering munitions. This may also explain the ongoing attacks against Ukrainian civilian targets to tie down such systems, although Ukrainian forces use decoys and other methods to weaken such attacks.[348][349]

On 17 June, the UK MoD wrote on Twitter: "In the constant contest between aviation measures and counter-measures, it is likely that Russia has gained a temporary advantage in southern Ukraine, especially with attack helicopters employing longer-range missiles against ground targets", while noting that imagery showed more than 20 Russian attack helicopters had been deployed to Berdiansk Airport.[350]

By 11 July, counter battery fire from Ukrainian artillery was proving to be more accurate. This was due to most Russian forces lacking "counter-battery radar systems". Ukraine has a number supplied by the United States. Combined with cheap drones Ukraine has destroyed 32 Russia artillery pieces for the loss of eight of their own according to open source intelligence.[351][352][353] On 13 July, dismissed Russian Major General Ivan Popov released an audio message. In the message, Popov complained about a lack of "counter-battery combat" systems to find and stop Ukrainian artillery, which he said was responsible for "the mass deaths and injuries of our brothers in enemy artillery fire."[354]

One Ukrainian soldier spoke of Russian airpower: "Russian helicopters, Russians jets fire at every area, every day". On casualties, one soldier said "We have lost a large number of people." Russian artillery, specifically Grad rockets, have been effective. Another soldier reported his son being hit directly by a kamikaze drone just before the counteroffensive began. Being summer, the Ukrainian soldiers report high temperatures. One soldier isn't wearing body armor while another told the BBC he took his shirt off specifically due to the heat despite many "mosquitoes and horseflies". Ukrainian soldiers also mentioned minefields that they had to cross in order to make assaults. In June, the BBC was told that most of the Ukrainian forces were being held in reserve for a "big enough opening in Russian defences to launch a main attack".[355]

Other tactics and equipment

On 18 June, the UK MoD wrote on Twitter that Russian forces were "often conduct[ing] relatively effective defensive operations" during the counteroffensive, with Ukrainian forces making "small advances" in "all directions".[299]

Western-supplied equipment including night vision may be giving Ukrainian forces "tactical advantages" during night fighting, according to Russian sources cited by the ISW, who say this would make it easier for Ukraine to conduct nighttime attacks.[356]

On 2 July, a major with the 37th Marine Brigade complained about the lack of armor on the AMX-10 RCs that the brigade uses, making them dangerous for crews, as well as their unsuitability in Ukrainian terrain despite praise for their guns and optics. One vehicle was destroyed by shrapnel from a 152 mm shell that detonated the ammunition, killing the crew of four. These vehicles are not designed for frontal attacks but for armoured reconnaissance and fire support.[357][358]

Ukraine has made widespread usage of decoys, in particular fake M777 howitzers costing under $1000 whereas the actual weapon costs several million dollars to make. Decoys use steel and wood to match the infrared signature that a real M777 would give off. Fake HIMARS launchers have been used by Ukraine since August 2022. Russia has also used fake trenches filled with explosives to kill Ukrainian soldiers.[359][360][361]

Russian command

Structure

On 9 June, the ISW assessed that it was unclear who was really in charge of the Russian defensive operations. There was speculation that Alexander Romanchuk, Mikhail Teplinsky, Sergey Kuzovlev, or Valery Gerasimov could all be the district commander, with the ISW assessing that there are "likely overlapping" commanders.[107]

On 8 September, the Center for Security and Emerging Technology reported that Russia has been reorganizing their command into a singular horizontal organization and have been moving their command posts further behind the front-line to prevent airstrikes against command structures. CSET concluded that Russia is attempting to combine the various regular and irregular units into a common command space with a singular commander.[182][362]

Issues

There have been numerous reports of Russian commanders low on the chain of command complaining about mismanagement by the high command, only to be fired immediately after.[363]